News

Corinne Deloy,

Helen Levy,

Fondation Robert Schuman

-

Available versions :

EN

Corinne Deloy

Helen Levy

Fondation Robert Schuman

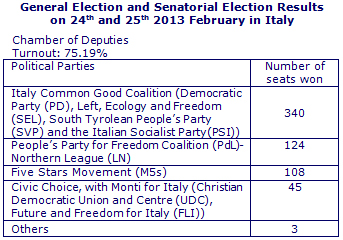

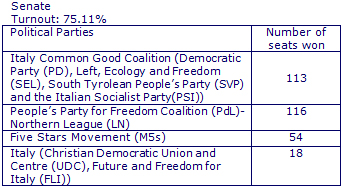

The worst scenario finally emerged in the parliamentary elections that took place in Italy on 24th and 25th February. The opposition coalition Italy Common Good (Democratic Party, PD), Left, Ecology and Freedom (SEL), the South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) led by Pier Luigi Bersani won 29.54% of the vote, taking 340 seats in the Chamber of Deputies (Camera dei Deputati), pulling just ahead of the rightwing coalition (People's Party for Freedom (PdL)- Northern League (LN) led by former President of the Council Silvio Berlusconi (1994-1995, 2001-2006 and 2008-2011) (PdL) which won 29.18% and 124 seats. In the upper chamber, the Senate (Senato della Repubblica) the coalition Italy Common Good came first with 31.63% of the vote and 113 seats, with too weak a lead to be able to form a majority, since the PdL-LN coalition won 30.72% of the vote and 116 seats. The Five Stars Movement (M5s) led by populist Beppe Grillo won 25.55% of the vote and 108 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 23.79% of the vote and 54 seats in the Senate. The centrist coalition Civic Choice (Scelta Civica), with Monti for Italy (Christian Democratic and Centre Union (UDC)-Future and Freedom for Italy (FLI)) led by the outgoing President of the Council Mario Monti came fourth winning 10.56% of the vote and 45 seats in the Lower Chamber and 9.13% and 18 seats in the Senate. The leftwing coalition Civil Revolution (Italy of Values, IdV), the Communist Revival Party (PRC), the Italian Communist Party (PdCI) and the Green Federation) led by Antonio Ingroia did not achieve the threshold of 10% of the votes cast to have a representation in the Chamber of Deputies.

Since equal bicameralism is in force in Italy, which means that both Chambers enjoy equal power (article 55 of the Constitution), it is impossible to govern the peninsula if the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate do not have the same majority. The situation which has emerged after the parliamentary elections, a first since this electoral system was established in 2005, by Silvio Berlusconi, means that there is stalemate and in, the short term, it will be impossible to govern the country.

We should remember that the majority bonus granted to the coalition that wins the election is calculated differently in each of the two chambers of parliament: it is granted to the party (or coalition) that comes first nationally in the Lower Chamber but granted regionally in the Upper Chamber, where it is given to the party that comes first in each of the regions. "We have a country which is ungovernable both politically and technically with few solutions based on almost impossible alliances that are numerically inadequate," indicated Massimo Razzi a journalist writing for the daily La Repubblica on the situation which the elections have led to.

Turnout totalled 75.19% for the Chamber of Deputies and 75.11% for the Senate.

Source : Italian Interior Ministry

http://elezioni.interno.it/senato/scrutini/20130224/index.html#camera/scrutini/20130224/C000000000.htm

Source : Italian Interior Ministry

http://elezioni.interno.it/senato/scrutini/20130224/index.html#camera/scrutini/20130224/C000000000.htm

Source : Italian Interior Ministry

http://elezioni.interno.it/senato/scrutini/20130224/index.html#senato/scrutini/20130224/S000000000.htm

Source : Italian Interior Ministry

http://elezioni.interno.it/senato/scrutini/20130224/index.html#senato/scrutini/20130224/S000000000.htm

"Even though there is a majority in the Chamber of Deputies and another in the Senate, there is no government," declared Stefano Fassina of the Democratic Party. "The country is facing an extremely difficult situation," declared the leftwing opposition leader, Pier Luigi Bersani. "We shall a responsibility to manage a situation produced by the elections in Italy's interest," he added. The left has seen its dreams of an alliance with Mario Monti's centre shattered, since the latter suffered severe defeat. Therefore it cannot achieve a majority in the Senate to govern the country. The opposition has fallen victim to M5S which made a real breakthrough, taking votes both on the left and the right.

Pier Luigi Bersani campaigned saying that if he won he would not undo the austerity policy undertaken by outgoing President of the Council Mario Monti and that he would not change the retirement reforms, nor would he reduce taxes, or increase public spending. "We shall continue the policy of systematically assessing spending that Mr Monti introduced and we shall not question the retirement reform," indicated Enrico Letta the Deputy General Secretary of the Democratic Party. The left only promised to undertake a more social policy.

The outgoing President of the Council Mario Monti is the grand loser in this election. The Italians voted against the austerity policy introduced since he took office in November 2011. The Professore suffered a terrible defeat; undeniably he failed in his wager to become the leader of the reforming centre, rid of Silvio Berlusconi and the Northern League. "Mario Monti's second mistake is the following: a technical government has to set two or three goals to achieve and not target the long term. By saying that he would govern until the elections Mario Monti submitted to the parties which set the pace and the degree of the reforms," stressed Franco Debenedetti, a company head.

"People appreciate him for his technical abilities as well as for his 'sang-froid' which placed him above the crowd and allowed him to make Italy credible again. But once he launched into the political battle he embraced the rules to the point of becoming aggressive with his rivals," indicated Stefano Folli, an editorialist for the economic newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore. "His popularity mainly rested on his non-political status," analyses historian and sociologist Marc Lazar, who points to the 'malaise' created by the support of the European institutions and the leaders of Europe to the President of the Council, who wanted the reforms introduced by Mario Monti to continue.

Although Mario Monti undeniably helped to stave off the dangers of a systemic crisis in Italy and reassured the financial markets during his mandate as Italy's leader; he was however unable to undertake a number of reforms which he has had to leave incomplete. Worse still he gave the impression that he was recanting during his electoral campaign, for example when he explained for months that the re-introduction of the tax on the main place of domicile (Imposta municipale unica, IMU) was absolutely vital, he then anticipated reducing it, likewise income tax. "I shall not stay in politics at all costs," said Mario Monti whose political future does indeed seem compromised.

Silvio Berlusconi, unlike Mario Monti, won his bet and succeeded in making an impressive come-back just 15 months after his departure from government to the backdrop of booing crowds. "It is an extraordinary result which shows that those who believed Silvio Berlusconi finished should think again," said a delighted Angelino Alfano, leader of the PdL. The Cavaliere really did revive his party which had been weakened by internal divisions. His promises to pay back the IMU tax, of a tax amnesty and the reduction of fiscal pressure – which he said he would fund thanks to a reduction in public spending and especially the creation of 4 million jobs, visibly convinced the Italians who were sorely affected by the austerity policy introduced by the Monti government. During his last TV appearance the Cavaliere again promised to raise retirement pensions of the poorest. "These Italian want to continue dreaming as if Italy was not experiencing the worst crisis since the war," stressed Ilvo Diamanti, a professor of Political Science at the University of Urbino.

Undeniably the right remains strong in Italy. "Hostility to the left is truly established in the country. It is the result of the former powers of the Communist Party and as the possibility of a leftwing government emerges then this sentiment resurges," explains Marc Lazar.

Populist Beppe Grillo seems to be the true winner in this election. A major share of the Italian population obeyed his last order given in the Saint-Jean de Latran Square in Rome during his "tsunami tour", the name given to his electoral campaign, undertaken aboard a minibus far from the TV studios, which he boycotted, at public meetings in many towns: "Let's send them all back home!" "In three years we have become Italy's biggest party (...) history will change slightly, let's see how," he declared, adding "they are finished, both on the left and the right. They will last 7 or 8 months but we shall be a real obstacle to them." He qualified the results as being of "world importance" "We shall be an extraordinary strength. We shall have 110 seats in Parliament but outside there will be millions of us. We shall do everything we have said we shall do and leave no one behind." shouted the M5S leader. He succeeded in attracting the discontented to his name – those who have most severely affected by the socio-economic crisis (the peninsula has been in recession since the third quarter of 2011 (- 2.2% in 2012) and is not due to emerge from this before the end of 2013) and the outgoing President of the Council's austerity policy, those tired of the escapades of the ageing political classes, and those exhausted by the corruption scandals. Moreover his criticism of the "pro-European elites" and his various promises (reduction of working time to 20 hours per week, the payment of a citizenship revenue of 1000€ per month for three years to any Italian that needs it, the abolition of public funding of all political parties, the reduction in the number of and salaries of MPs, a referendum on Italy's membership of the European Union and the euro zone) enabled him to take votes from the left and the right. Silvio Berlusconi understood this declaring, "Voting Beppe Grillo, means voting for the left."

If we add together the votes won by M5S, the small far right and far left parties, without including the PdL-LN coalition, those hostile to EU made an impressive breakthrough. "It is the first time since the 1970's that Europe has been the focus of debate, it has become the issue of political division whilst to date it represented a subject of consensus," stresses Marc Lazar adding, "it is not euroscepticism as such, but the increasing doubts about European integration, that have been visible for years, are now focusing on the euro – which has become the symbol of expensive living – and on questions about the opaque nature of the European institutions and their lack of democracy. To this we should add the rejection of the austerity policies since it is believed they are set from the outside."

After the breakthrough by M5S we might wonder about the strength of the organisation long term since internal tension has already emerged.

It is now up to the President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano to draw the conclusions of the results of the election on 24th and 25th February. He might try to form a government of national unity which would commit to budgetary austerity goals and a new electoral law. Indeed further elections organised according to the present voting method might end in a similar result.

The Vice-President of the Democratic Party, Enrico Letta ruled out the possibility of another round of elections. "Whoever the winner is it will be up to them to put forward the first proposals to the President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano," he stressed adding, "Going back to ballot does not seem to be the best option."

If the stalemate lasts and makes the formation of a government coalition impossible Italy will have to organise a new parliamentary election, as in Greece last year – which the peninsula now resembles, and not just because of the unstable political situation. According to article 61 of the Constitution new elections might be convened within 70 days.

On the same theme

To go further

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

20 January 2026

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

13 January 2026

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

4 November 2025

Elections in Europe

Corinne Deloy

—

28 October 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :