Budget and Taxation

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

Honorary Advisor to the Senate, specialist in budgetary issues

1. The 1%, linchpin in the budget negotiation

1.1. The MFF negotiation, a budgetary negotiation

1.1.1. Reminder of the procedures

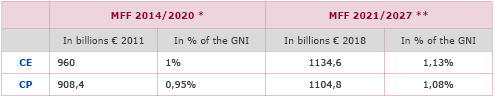

The negotiation of the multiannual financial framework (MFF[1]) is Europe's main budget negotiation. It takes place every seven years. The MFF sets the expenditure ceilings and their division into headings. Even though this is only a framework to cap spending, it mainly defines what the Union's annual budget will be for the programme's seven-year duration. These totals are expressed in credit commitments (CC) which correspond to the spending that the budget authority[2] will be allowed to commit to yearly. These commitments are turned into payment appropriations (PA) which correspond to predictable disbursements in proportion to the Union's GNI. For the multiannual budgets of 2014/2020 and 2021/2027, the figures are as follows:

Main data of the MFFs 2014/2020 and 2021/2027.

*Council regulation 1311/2013 of 2nd December 2013

**Commission proposal, COM (2018) 321 final 2nd May 2018

The negotiation starts with a proposal by the Commission but takes place between Member States. The negotiation last two years in general. The MFF takes the shape of a Council regulation, adopted unanimously, after approval by European Parliament. In reality this regulation takes up the arbitration finalised during the European Council. A crisis council in which negotiations are always tense, before targeted adjustments (last minute concessions and "budgetary gifts") enable a consensus and a final decision.

Even though the political situation is forcing changes to rebalance headings or to create new ones, experience shows that all States address the negotiation acutely aware of their budget interests. Their weight in the budget's financing, the importance of European returns, the contributive position[3] are the objective data of the Member States' position in the negotiation. These data are fundamental and notably explain the place given to other institutions.

1.1.2. The budget negotiation and the institutional triangle

The Commission and Parliament on the one side and the Member States on the other have a quite specific place in the budget negotiation and understand them differently.

- The budget negotiation takes place between the States. But the Commission, which has a monopoly over initiative, makes the proposal. It has a decisive role to play in the formal presentation, structure and naming of the headings, a sign of the Union's political priorities[4]. However, the amounts are rather more indicative. The Council often deviates from the amounts put forward by the Commission.

The role of the European Parliament is as limited. Of course, it is involved in the negotiation[5] and has to approve the MFF by a majority vote before its adoption by the Council. But this simple approval is an issue of power in the institutional triangle. Parliament has therefore succeeded in subordinating its approval to a flexibility clause between headings or commitment to reform (regarding financing for example). On the other hand, the amounts, after two years of negotiation and political arbitration at the highest level, seem difficult to change. In the 2007/2013 MFF, the agreement in the Council was €862.4 billion; the Interinstitutional Agreement, after Parliament's request, was concluded for €864.3 billion, or +2 billion over seven years. For the 2014/2020 MFF, not a single euro has been added to the European Council compromise.

- The approach to negotiation is also different. The Commission assesses budgetary needs in the light of its proposed objectives and then adds up the allocations. The total is close to the maximum authorised in an own resource decision (ORD) which governs the budget negotiation and sets a sort of absolute ceiling for the MFF[6]. In 2019, this ceiling lies at 1.20% of the GNI in terms of payment appropriations and 1.26% in terms of the credit commitments. "The Union can finance itself with its own resources to make payments up to 1.20% of the sum of the GNIs of all of the Member States." Parliament follows the same logic, calling for the above-mentioned ceilings to be exceeded[7], the only way in its opinion to rise to current challenges.

The Council does not function according to an addition of priorities, but starts by setting an envelope, like an architect who asks his client not "what do you want" but "how much do you have? Hence the overall envelope is always significantly different from the maximum allowed.

1.2. The recurrent debate over the 1%

1.2.1. The ritual debate over the level of the European budget

For twenty years now economists have been advocating for a European budget of 3.5% or 7% of the GNI so that is has real power of influence and stabilisation. For twenty years parliamentarians (both national and European) have supported this increase so that the Union can rise to the challenges of the day and to legitimate European goals. The 1% threshold does indeed seem derisory: in 2009 and 2010 alone the Union's budget was below that of France! But this pressure has never dented the Member States' resolution to restrict the budget within its tight limits.

This insistence by the States can be explained by the way the Union's budget is financed and balanced. Despite the myth of financing with own resources[8], 85% of these (VAT and GNI) come from national contributions levied on the Member States' tax revenues[9]. The Union's budget also has the privilege of never being in deficit because of the automatic adjustment of revenue to expenditure voted by the budgetary authority. While the balance of the State budget is ensured by the use of debt, the balance of the European budget is ensured by the contribution based on the GNI of each State. And whilst the European budget is quite independent of the economic situation, the Member States are obviously more sensitive to current budgetary difficulties and are reluctant to increase the budget.

An increase in the Union's budget is always possible but three situations must be distinguished:

- An increase in the budget in terms of payment appropriations up to 1.20% of the GNI, a ceiling set in the decision for own resources (ORD), is perfectly possible under the present framework and is only dependent on a budget agreement between States. This ceiling is applicable to own resources, i.e. payment appropriations, therefore disbursements. It is therefore amount of payment appropriations which leads to the resource total and as a result the States' contribution to the Union's budget.

- An increase in the budget beyond 1.20% of the GNI supposes a new ORD, a unanimous Council decision after consultation with the Parliament but after ratification by the Member States. Although Parliament support is a given, that of national parliaments is less certain.

- In both cases, the budget would continue to be financed under the current system, which is overwhelmingly based on Member States' contributions. A budget financed by a European tax approved by Parliament would suppose a new treaty, since Parliament does not have any fiscal competence. This possibility appears to have been ruled out in the short term.

The increase in the budget is therefore only one in the current margin between 1 and 1.20%.

1.2.2. A time of tension between Member States

Wrangling over the 1% has therefore been ongoing for the last twenty years[10] between two camps.

On the one side there are the supporters of budgetary restraint or the control of spending or "better spending", sometimes berated as "the skinflint club". These States are de facto allies in the budget negotiation and can be identified by common positions or letters of intent addressed to the Commission. Most often they are the biggest contributors and/or net contributors. Most often the States do not immediately say whether the 1% applies to the credit commitments or appropriation payments, thereby allowing a negotiation margin. In the MFF 2007/2013, the 1% threshold applied to payment appropriations. In the 2014/2020 MFF the 1% threshold applied to credit commitments.

Opposite them are the Commission and the Parliament, supporters of a budget that will enable the development of new policies, as well as States satisfied with the existing situation in which adjustments are of benefit to them. In truth the "payers" camp has always won. The main contributors, particularly Germany, the leading contributor (20%) and first net contributor (13 billion € per year) has imposed a budget at 1% for the last 20 years.

This framework, set by the contributors always goes together with adjustments, sometimes in the last moments of negotiation[11], to the benefit of some States. These contribution adjustments (differentiated call rates, flat rate reductions, etc.) or targeted allocations to a particular State lead to a consensus within the Council.

1.3. A significant budgetary stake

Why is there so much tension over the 0.1% or even 0.01%? Without ignoring the symbolic nature of this threshold, exceeding the 1% represents a major budgetary challenge for the States.

1.3.1. The 1%, a symbolic and political threshold

Most European citizens only have a vague idea of what the European budget represents; how it is financed and the spending it finances. The amounts are completely abstract whilst the issues at stake concern hundreds of billions of €! 975, 1000, 1315 billion € in seven years? Expert debates on current/constant euros or constant scope reasoning are too complex. The 1% is a simple, clear cue. Likewise, the MFF is, beyond its budget function, a communication tool that clarifies the Union's budget choices, the 1% is a threshold that can be understood by all. It helps us see whether the Union's budget is increasing (slightly) or remaining stable.

1.3.2. A major budgetary issue

This derisory percentage concerns the Union's GNI or rather the sum of the Member States' GNIs. The budgetary issue is therefore significant.

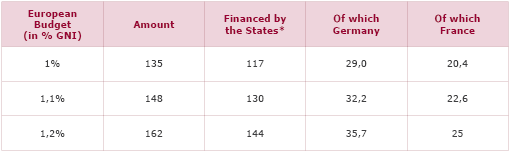

The Union's GDP[12] totalled 13.500 billion € in 2019. An annual budget of 1% therefore represents 135 billion € (945 billion over seven years). Each budget increase of 0.1% represents 13.5 billion € 85% of which is financed by the Member States[13], after deducting customs duties, pro-rata of their share in the Union's GNI. Hence for Germany (24.8% of the GNI) means an additional contribution of 3.2 billion and for France (17.4% of the GNI), 2.2 billion.

Main budget challenges in a budget at 1%, 1.1% and 1.2% of the GNI (in billions €)

*The amount of customs duties, constant whatever the level of the budget is estimated 18 billion.

1.3.3. The 1 %, an important but flexible threshold

This 1% threshold can be bypassed in several ways.

- Growth forecast uncertainties. This 1% threshold combines a figure (the amount of the budget in billions of euros) and a GNI forecast formulated before the adoption of the MFF. This forecast involves a degree of uncertainty and, consequently, the final level may vary significantly depending on growth results. In the event of a slowdown in growth, if the amount of the budget is still in line with the MFF ceilings, its share in GNI necessarily increases[14].

- The gap between commitment and payment appropriations. In general, States are especially attentive to future disbursements. Their amount leads to that of resources, which in turn leads to that of national contributions. The consideration of returns is secondary. In the 2016 referendum, the Brexiters' leader spoke of the British contribution to the Union's budget, omitting the returns. Thus, States tend to neglect commitment appropriations, which might possibly be financed later by other governments! This gap between commitment and payment appropriations is an easy solution for States that can show a certain ambition in commitment appropriations and a limitation on payment appropriations. Easy but dangerous. The unspent commitments, which match the appropriations that have already been committed but not yet paid is considerable: nearly 300 billion in 2019!

- Non MFF allocations. These budget lines - so-called non MFF[15], flexibility measures and special instruments - help finance unplanned spending, unprogrammable by definition and increase the category ceilings if necessary. But it has to said that this is also a means to increase spending without openly challenging the ceilings[16].

- Off budget financing. The Union budget is not the only way to finance European spending. The Union has other financial instruments to support investments or to help the States in difficulty[17]. In other words, it is possible for Europe to have an ambitious, effective policy with a controlled budget.

2. The specific features of the MFF negotiation 2021/2027

2.1. The consequences of Brexit

2.1.1. Direct effects

- The budgetary effect: a net loss for the budget. Brexit will lead to a loss in revenue estimated at between 10 and 12 billion €. The UK was the second net contributor after Germany. This loss is linked both to the British contribution to the budget and customs duties. However an agreement was reached in December 2017 planning for the country to continue paying its contribution to the budget until the end of the present MFF; and that they would commit to paying the remaining sums it was committed to due to its prior membership of the Union (spending by British European officials for example), and due to the difference between previous commitments and payments. The "bill" is said to be around 40 to 45 billion €.

- The statistical effect: the UK enjoys a special contribution scheme. The British rebate enables a reduction of its net contribution. The country is reimbursed two-thirds of the difference between its contribution to the budget and the total of European expenditure. Hence there is a difference between the British share in the Union's GNI (15.2%) and its share in financing (11.5%). As it leaves the European Union, the UK will be reducing the Union's GNI rather more than it will be reducing its share in the financing of the budget. The Union's GNI without the UK (13.480 billion €) will be 15.2% lower than the Union's GNI with it included (15.900 billion €). Hence for a given total of the budget its share in the Union's GNI increases.

2.1.2. The indirect effects

- The end of the rebates. The UK was not the only Member State to enjoy an adjustment to its contribution. Four other States have benefited from a rebate given the "excessive imbalance" of their budgetary burden: Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands and Austria. The share of their participation in the financing of the British rebate was reduced by a quarter of the total that would have resulted from a normal pro-rata sharing in the Union's GNI. This "rebate on the rebate" is financed by the other States. This adjustment helped contain budgetary imbalances between the Member States concerned by the Union's budget[18]. With Brexit, the adjustment will disappear. The States will no longer enjoy any budgetary privilege.

- Germany will be losing an objective budgetary ally. Experience shows that in the budget negotiation Germany and the UK had similar interests and defended common positions. Although several countries supported a rigorous budgetary framework, in the two previous MFFs, the setting of the budget at 1% (1% in payments in the MFF 2007/2014 and 1% in commitments in the MFF 2014/2020) is greatly linked to the alliance between these two countries.

In the MF 2021/2027, the 1% is still being defended by Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark, all three being net contributors.

2.1.3. British capacity to cause harm intact

- A no-deal Brexit would have major budgetary consequences. The UK might not have to pay its contribution to the 2020 budget. According to the Commission the loss of around 12 billion might be financed by a reduction in the 2020 budget of 6 billion and an additional contribution by the Member States of 6 billion. Moreover, due to the difference in calculation in the British adjustment, the States would have to pay this adjustment even if the British do not participate. And especially, it would not have to pay its share of previous commitments. In other words, a loss of 40 billion.

- But there is another more embarrassing hypothesis. The agreement over the total of 40 billion takes into account the British share in the financing of the 300 billion € unspent commitments (RAL). If the UK conditions its contribution to simultaneous payments by the other Member States, the latter would be obliged to pay their share of the RAL, i.e. around 20% for Germany (60 billion) and 16.8% for France (50 billion €).

2.2. Negotiation Outlook

2.2.1. Latent debate over net balances

The idea, accepted by all, is that the departure of the UK also ends the debate of fair return, which was the reason behind the British rebate. The arguments are known to all: the mediocrity of an accounting approach ignoring the advantages of European integration, the lack of solidarity between States, between rich and poor countries, the problems in assessing nets balances[19]. For the Commission Brexit will provide an opportunity to bring all types of adjustment to an end.

If the accounting approach is undeniably simplistic and questionable, it has to be said however that all States calculate this net balance and that the rebates are not designed to guarantee the balance between contributions and returns, but only to correct "excessive imbalances". Despite its rebate the UK was always been the second net contributor in the Union. Any new spending is screened in light of its returns by the States[20].

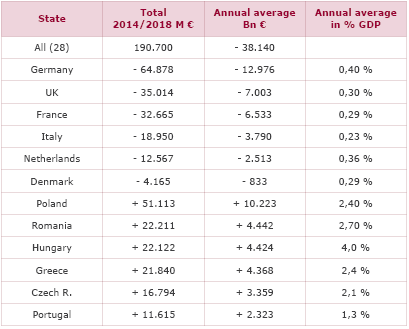

In truth, thanks to the net balances, the budget is a tool of solidarity and ensures a massive redistribution between net contributor States and net beneficiaries. Each year 38 billion € go from one to the other. A redistribution which no State even dreams of challenging, even those which support the containment of the budget.

Main data about net balances

(budget spending by the Union in the State - contribution by the State to the Union's budget)

Source : Commission Financial Report 2018, editing by the author

However, the issue of the "excessive imbalances" remains[21]. According to German government estimates Berlin's net contribution to the European budget will more than double in the next few years, rising from 13 billion € in 2020 to 22 billion in 2027. Denmark's net contribution is due to rise to 13 billion.

There are several ways to limit these imbalances: rebates, capping of net profits (more than 10 billion per year for Poland[22]), the capping of net balances etc ... all of these ideas have already been ruled out in order not to fall into the rationale of adjustment. But is this position tenable? By rejecting all of the possibilities for adjustment and stabilisation the Commission and the Parliament seem to be denying that the increase in the States' contributions could lead to political and budgetary problems. On 17th October 2019, the German Chancellor indicated in the Bundestag that the German contribution was going to increase "disproportionately" and that she "was going to discuss a fair distribution of the burden". It is difficult to see how the other Member States will escape this reassessment.

2.2.2. Between 1% and 1.1%?

1% it seems is untenable. Simply because of the delayed effect of Brexit on the budget's financing and the Union's GNI. If the GNI decreases more than financing - the only support to the budget at its present level will lead to an increase in the share of the GNI. Conversely the upkeep of a budget at 1% would imply a reduction in the level of the budget.

A moderate increase therefore seems inevitable. In practice it is impossible to finance any further spending without trimming the old ones. The most painless solution would be to maintain allocations in current euros, which would lead to a real reduction, in line with inflation. This is the solution that has been used for the last 20 years for the CAP. The nominal amount is nearly identical, which means a real reduction. The reduction of the CAP, which Germany wants, seems to be certain now despite the objections expressed by the French and the MEPs in the AGRI committee.

Likewise, some new financing will not last the budgetary cuts. This is the case with military spending. The Commission has planned a concerted effort in the military area with three types of financing: the financing of investments and research with the European Defence Fund (EDF - 10.3 billion €); a "mobility" programme (6 billion) designed to enable the adaption of engineering structures and major infrastructures to the requirements of the States' armies[23] ; and the financing of external operations, via a European Peace Facility (10.5 billion) but not as part of the MFF. It is likely that the EDF alone will be saved. But it is uncertain that the amount will be maintained, and the proposal made by the Finnish presidency leads us to fear for projects which are however a priority.

Experience shows that States always tend to privilege existing spending, which maybe imperfect, but whose distribution is known, over new spending, which may undoubtedly be timely, but is often arguable and the distribution of which still uncertain.

2.2.3. The bid for conciliation on the part of the Finnish presidency

The Commission made its proposal in May 2018 and published its draft sectoral regulations in June. The negotiation phase was launched aiming to estimate the Member States' positions then converging them. Three presidencies have succeeded one another: Austrian, Romanian and Finnish. Pressure has evidently grown at each stage. During the European Council on 20th and 21st June 2019 the heads of State and government invited the Finnish Presidency to refine the negotiation box in a bid to finalise a political agreement before the end of the year. Progress in the work was rather slow until Germany took a public, quantified position.

The hard phase of negotiation can now start. The Presidencies proceed by successive iterations. Experience shows that the Finnish Presidency's first costed proposal is approaching final arbitration. On 2nd December last year, Finland proposed a ceiling for payment appropriations of 1.07% of GNI, or 1 087 billion for 7 years. This threshold is top of the range... and constantly revised downwards. The iteration process can now begin. It is already certain that the level of the budget (in payment appropriations) will be between 1% and 1.05%. Between €135 and 142 billion. But will the 1%, the lower range of negotiation (as for the 2007-2014 MFF), be accepted by the largest contributor, or its maximum acceptable limit (as for the 2014-2020 MFF)?

Germany will, as always, be the ultimate decision-maker. The negotiation is now focused on €7 billion annually. It will end with a symbolic increase and "budgetary gifts" to the most reluctant Member States which will be a credit to no one. But that is the way it has been... for the last twenty years.

[1] The practice of drafting a multiannual budget framework in the shape of a "financial perspective" has existed since 1988. The Lisbon Treaty institutionalised this practice as the multiannual financial framework. The MFF is set out in the articles 312 and the following of the TFEU.

[2] The budgetary authority comprises the European Parliament and the Council. While the MFF is adopted by the Council, the annual budget is adopted by the budgetary authority.

[3] Difference between the expenditure of the European budget in the State (returns), and its contribution to the budget, showing net contributors and net beneficiaries.

[4] The word agriculture was removed from the 2007/2013 MFF and CAP expenditure was included under a heading "conservation and management of natural resources"; the 2014/2020 MFF is clearly growth-oriented (with a heading 1 "smart and inclusive growth" and a heading 2 "sustainable growth"); the 2021/2027 MFF changes the heading cohesion to "cohesion and values" and is enriched with two new headings "migration and border management" and "security and defence". Values, borders and defence, three new concepts that give political meaning to the draft budget.

[5] Art 312 § 5 of the TFEU.

[6] This ceiling, known as the own resources (OR) ceiling, was set at 1.27% of GNI in 1988. The ceiling corresponds to the ceiling for payment appropriations. This percentage corresponded to an assessment of GNI according to current national accounting standards, as derived from the European System of National Accounts (ESA), derived from the United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA). The ESA is regularly amended. These changes effectively increase the States' GNI. Thus, the ceilings expressed as a percentage of a revalued GNI are revised downwards. The DRP of 26 May 2014 had set the ceiling at 1.23% and 1.29%. After the entry into force of the new accounting system (SEC 2010), these ceilings were reduced to 1.20% and 1.26%.

[7] Parliament adopted two resolutions, on 14 March and 30 May 2018, proposing to increase the amount of commitment appropriations to 1.3% of GNI, in line with MFF 2021/2027.

[8] Article 311 of the TFEU

[9] VAT and GNI resources differ in their calculation method (the former results from a complex calculation based on the product of output VAT, the latter is calculated pro rata to the share of GNI in the total GNI of the Union) but both result in the same levy on tax revenue.

[10] It is necessary to go back to before 2000 to have Union budgets higher than 1% of GNI. The budget was on average 1.18% in payment appropriations between 1993 and 1999.

[11] At the European Arbitration Council, the Heads of State and Government are in direct contact with the budget services.

[12] Eurostat's available data refer to gross domestic product (GDP). The transition to gross national income (GNI) requires taking into account net incomes from abroad (cross-border workers' salaries, patents) which, at European level, are minor.

[13] Other own resources (customs duties) remain stable regardless of the amount of the budget. It is assumed that, in the absence of new own resources, any increase is financed by the Member States alone.

[14] In 2016, for example, due to lower than expected growth, the share of commitment appropriations was 1.05% of GNI instead of the 1% set in the MFF.

[15] These non-MFF lines were introduced in the 2000/2006 financial perspective in order to give an element of flexibility to the rigid framework of the MFF. They are provided for in the MFF Regulation, which distinguishes between flexibility measures that allow ceilings and special instruments to be exceeded, which can be mobilised in an emergency (Emergency Aid Reserve and EU Solidarity Fund in the event of a natural disaster), flexibility instrument and European Globalisation Adjustment Fund.

[16] Thus, in 2006, the Commission was able to formally present a proposal for a MFF 2007/2014, very well controlled at 1% but by supplementing the MFF ceilings with expenditure outside the MFF up to 56 billion. Amounts that the States have partially reinstated in the MFF.

[17] Loans from the European Investment Bank (EIB), the European Investment Fund (EIF), such as the European Strategic Investment Fund (SIEF). The Juncker plan should make it possible to mobilise €500 billion of investment between 2015 and 2020 and is based on a guarantee fund from the EU's €16 billion budget

[18] Without this adjustment on the financing of the British rebate, Germany's net balance would have increased by €1 billion (€14.4 billion instead of €13.4 billion in 2018).

[19] The Commission recognises three different ways of assessing net balances depending on whether administrative expenditure is taken into account and customs duties are included in States' contributions.

[20] The consideration of budgetary returns is infiltrating most policies. The implementation of the satellite positioning system (Galileo), which involves nanosecond calculations, has long been blocked by a debate on the agency's headquarters (ultimately Prague). More recently, Poland has questioned the usefulness of the European Defence Fund as a means by which rich states can increase their returns.

[21] There is no definition of this excessive imbalance, but according to the formula of a former budget director, an imbalance is excessive when it is considered excessive by the State using this argument. Both the amounts and the political context are elements of this assessment.

[22] In ten years, Poland has received more than 100 billion (net balance) from the European budget. Is it still justified to maintain a flow of more than €10 billion 15 years after accession?

[23] A simulated exercise organised by NATO revealed that the armies were unable to move from one state to another. The weight of armoured vehicles made it impossible or very slow to cross engineering structures. The purpose of the mobility programme is to adapt the infrastructure to the loads of military equipment. Given that the costs of adaptation are enormous and that such infrastructure is the first to be targeted in the event of armed conflict, there is a risk that the mobility programme will be seriously curtailed.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :