European social model

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

-

Available versions :

EN

Stefanie Buzmaniuk

In a world where women's rights are once again being challenged from all quarters, Europe remains the place where women live best. Within the Union, however, there have been some setbacks, difficulties persist, and progress is still required in the political, economic and social fields to achieve true gender equality.

The global context is increasingly difficult for women

In the context of the pandemic, it was once again revealed that women are generally more affected by crises than men, and that they are still more vulnerable on average than their male counterparts. The pandemic has further weakened women: economically, with higher unemployment levels, in terms of health with greater exposure to the virus due to the overrepresentation of women in positions requiring physical contact and in terms of violence with an explosion in the number of requests for assistance following incidents of domestic violence. With the end of the pandemic, the situation for women around the world does not seem to be improving. The last two years have been bad for gender equality: the most striking example is certainly Afghanistan. Since the Taliban took power in the summer of 2021, Afghan women have lost their rights in almost every sphere - restrictions range from a ban on sports to the exclusion of girls from education as early as secondary school. In Iran, courageous women are taking to the streets en masse to win back their rights. Since the death of Mahsa Amini, following her arrest by the morality police in September 2022 for the "inappropriate" nature of her hijab, demonstrations have continued despite the brutal repression by the authorities. In Turkey, the Supreme Court confirmed the country's withdrawal from the International Convention of Istanbul Women's Rights in March 2021 by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The country officially left the Convention in July 2021. However, recent restrictions on women's rights do not only concern countries where their situation is traditionally unfavourable. The Supreme Court of the USA for example, overturned the "Roe v. Wade" bill on 25 June 2022 and repealed the constitutional right which had guaranteed access to abortion at federal level since 1973, thereby limiting the right that American women had deemed a given for decades. Russia's attack against Ukraine has also had a devastating effect on women's situation. Rape has once again made its way back into history, used as a systematic arm by the Russian army, representing an atrocious additional threat for women and girls living in the country at war. The Ukrainians who have left their homeland ahead of these threats, are mainly women (around 85 %) fleeing with their children - two of the most vulnerable categories to sexual violence and human trafficking. In some EU Member States, too, women's rights are in decline. This is particularly the case in countries where the rule of law is under threat. In Poland, the right to abortion has been significantly restricted and the Prime Minister has said that he intends to withdraw the country from the Istanbul Convention. In Hungary, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has noted significant shortfalls in the state's approach to addressing violence against women and highlighted recurrent discriminatory statements by politicians. The links between the decline in democracy and the decline in women's rights are evident.

Europe remains the woman's continent[1] - with progress to make

While women also face difficulties at EU Member State level, their situation remains better in the EU than anywhere else in the world. The principle of gender equality is one of the fundamental values of the European Union, laid down in the article 2 of the Treaty on European Union. Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights prohibits gender-based discrimination. However, there are still significant gender gaps in the European Union in the economic, political and social fields.

Economically, women remain disadvantaged

Equal pay for men and women for work of equal value has been part of the European treaties since 1957. Article 119, Title VIII, Chapter 1 states: "Each Member State shall during the first stage ensure and subsequently maintain the application of the principle that men and women should receive equal pay for equal work." Since then, Article 157 TFEU has been the legal basis for the principle of equal pay for men and women. Article 23 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights states that "equality between women and men must be ensured in all areas, including employment, work and pay". However, major differences in remuneration between men and women continue to exist in the European Union: 13% on average according to Eurostat. In Latvia, for example, the gender wage gap was 22.3% in 2020, but only 0.7% in Luxembourg. According to an OECD study, on average women earn 10.3% less than men in the European Union - in the OECD as a whole, the average is 12%. This makes no sense. For this reason, the European Commission proposed in March 2021, a draft directive as part of its Strategy to support equality between men and women and to strengthen the application of the principle of equal pay for equal work or work of equal value through pay transparency and enforcement mechanisms. A provisional agreement was reached on 30 November 2022 and the text was finalised on 15 December 2022 - which is a major step forward for women in Europe. In addition to the fact that women are financially disadvantaged in the world of work, they are still largely under-represented on company boards and therefore often deprived of real decision-making power. On average in the European Union 31.5% of the members of boards are women. Although this figure is still far from perfect parity, it is higher than in all other regions of the world: for example, in the United States it is 23.9%, in China 13.1% and in Japan 8.2%. At European level, the directive of 23 November 2022 on improving the gender balance of directors of listed companies and related measures states that, by 2026, "40% of non-executive director positions should be held by the under-represented sex" - which in the current context means women. The legal basis for this directive is sound. Article 23 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights states "The principle of equality shall not prevent the maintenance or adoption of measures providing for specific advantages in favour of the under-represented sex." Article 157 TFEU goes in the same direction and allows for positive action to strengthen the position of women. Lower wages and the fact that women often work shorter hours than men or are more likely to be in lower-skilled or part-time jobs has an impact on women beyond their active period in the labour market: they receive lower pensions than men. A study shows that the gender gap between pensions is considerable. On average, women in the EU receive 29% less in pensions than men. However, the gap has been reduced by 5 percentage points since 2010 - a development that marks progress in improving the overall economic situation of women. In its Strategy, the European Commission has identified the need to close this gap further as one of its main objectives. A concrete example of this is revealed in the debate on pension reform in France, where the specific situation of women is raised. Although the European Union is active in improving the situation of women in the economic world and remains a more favourable environment than other countries in the world, European women and girls are still penalised.

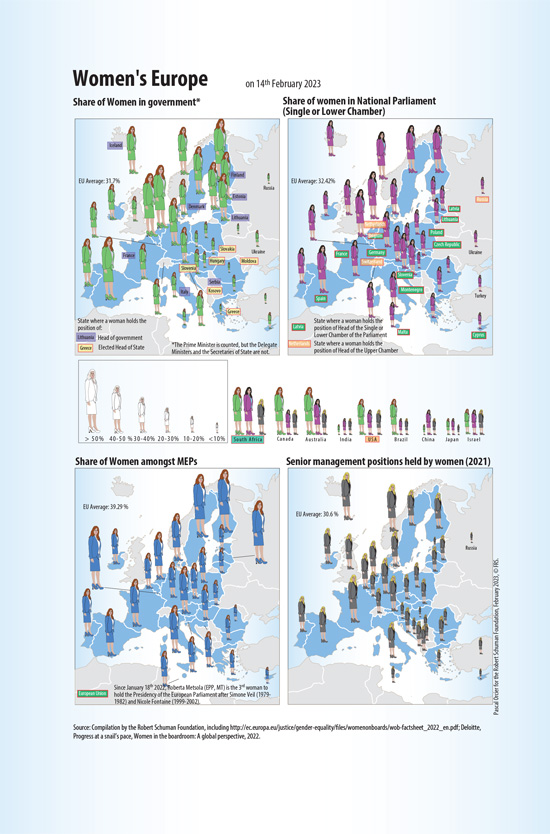

Female representation in politics in Europe is higher than elsewhere

Since the French journalist and great European, Louise Weiss, led a relentless fight to "a citizen of the woman" in the 1930s and another French woman, a great European, Simone Veil, was elected as the first President of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage in 1979, Europe has made considerable progress in the representation of women in the political institutions. At the highest political level, the European institutions have never been presided over by as many women as they are today: since 2019, the German Ursula von der Leyen is the first woman appointed to head the European Commission, French woman Christine Lagarde is also the first female to preside over the European Central Bank (ECB) - after having been the first to head the IMF - and since January 2022, Maltese Roberta Metsola is the third woman president of the European Parliament, after Simone Veil (1979-1982) and Nicole Fontaine (1999-2002). The Secretariats-General of the Commission (Ilze Juhansone since 2020) and the Council (Thérèse Blanchet since 2022) are also headed by women. This feminisation of the highest positions in the European institutions is welcome. However, it must be sustained - this will be one of the major challenges for the next political changes following the European elections in 2024. The European Commission is not perfectly equal, though - 44.44% of Commissioners are women. It should be noted however that this average is higher than that of the national governments of the Member States where currently 33% of heads of government are women. Furthermore, female representation in other non-European governments is often lower than in Europe: Brazil, Japan, India, Russia and notably China (with zero women in the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau) lie well below the European average. Within the EU, there are significant disparities. On the one hand, there are particularly high rates: 60.87% of the members of the current government are women in Spain, 57.89% in Finland and 53.33% in Belgium. On the other hand, some Member States have less pronounced female representation, such as Greece, where only two women are in government (8.33%), Romania (9.09%) and Malta (10.54%), and Hungary, where only one woman is in government (7.14%).

The number of women in parliaments is also higher in Europe than elsewhere, although parity is still not a reality. For the 2019/2024 legislature, 37.77% of the members of the European Parliament are women, which is higher than the average in the Member States, which is 31.53%[2]. Both of these rates seem quite high compared to the world average, which is 26%, and in comparison, for example, with the United States where the House of Representatives is composed of 28.57% women or with China which has 24.94% women in the National People's Congress. In general, the European Union stands out from other regions of the world with a higher representation of women in the various national and European political bodies. However, there is still room for improvement. Each new election, whether held within the Member States or at European level, will have to be looked at carefully to determine whether the results are moving in the direction of better female representation. In any case, such progress will require strong political will - from women and men in equal measure - to promote more women to the highest positions. Of course, this also presupposes that women can take their full place in a society in which significant obstacles are systematically placed in their way.

Women's place in society

Violence against women

With regard to gender-based and domestic violence, women are disproportionately targeted. Although gender-based violence also affects men in some cases, statistics show that women remain the most frequent victims. The pandemic once again highlighted this issue. According to a survey conducted by the European Parliament, 77% of women in the European Union believe that the Covid-19 pandemic has led to an increase in physical and psychological violence against women. In March 2022 the European Commission put forward a draft directive on combating violence against women and domestic violence, which aims to strengthen access to justice for women victims of violence, to criminalise forms of violence that were not previously criminalised (e.g. cyber-violence), to improve the prevention of violence and to strengthen cooperation between the Member States and the European Union. This proposal takes into account the planned accession of the European Union to the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. The Istanbul Convention was signed in 2017 by the EU but it has not yet been ratified. The path to accession is complicated by the fact that six Member States have not yet ratified it (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia) and others, such as Poland, may withdraw! Progress on this issue was made on 21 February 2023, when the Council formally asked Parliament to conclude the Union's membership of the Convention. Ratification of the Istanbul Convention by the Union in addition to the Member States would bring major benefits to the Union and give it an even sounder legal base to propose new legislation to combat violence against women. The MEPs' vote should be a formality, since in a resolution adopted on 15 February 2023, they stressed that "there is no legal obstacle preventing the Council from proceeding with the ratification of the Convention, as a qualified majority is sufficient for its adoption". In this respect, they refer to the opinion 1/19 of the Court of Justice of the European Union dated 6 October 2021, which clarifies the modalities for the accession of the European Union to the Istanbul Convention and confirms that the Council can proceed to its ratification by qualified majority, without having first obtained the agreement of all Member States.

Poverty is too often female

Poverty remains much more prevalent among women than men. UN Women, the UN entity dedicated to gender equality and women's empowerment, deems that in 2022, 388 million women and girls in the world were living in a situation of extreme poverty[3]. The share of European women is very low in this statistic: only 0.8% of women affected by extreme poverty live in Europe and North America. However, 11.2% of women versus 10.3% of men are in a situation of persistent poverty[4]. In Lithuania, 17.9% of women face this reality, compared to 14.2% of men. Even in countries with lower rates, women are still overexposed to poverty (e.g. Hungary, where the rate is 4.9% for women compared to 3.6% for men, or the Czech Republic, 5.1% compared to 2.6%). This is due to a number of factors affecting women: lower wages and pensions, higher unemployment rates, more part-time jobs, more unpaid housework than men, more single parenthood, etc. If all the projects are passed, the EU Gender Equality Strategy could have a positive impact in the fight to reduce women's poverty as it attempts to reduce gender inequality through a holistic approach, which takes on board all the factors that disadvantage women.

New technologies and their impact on women

With the emergence of virtual reality and in a rapidly changing technological context, new challenges for gender equality are emerging. This is why the Commission has included gender equality provisions in its proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (IA) currently under consideration by the co-legislators. Noting that "AI systems can perpetuate historical patterns of discrimination, for example against women", the Commission stresses that it is important to ensure that the development of new tools does not aggravate, or create, new discrimination. This regulation recognises that new artificial intelligence technologies can have a negative impact on fundamental rights and European values. This recognition is absolutely necessary to move forward with AI-related regulation. Carlien Scheele, Director of the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), stressed this during a conference in March 2022: "Artificial intelligence and gender equality are intimately linked. Indeed, AI is a human creation. And humans are not perfect." With this in mind, any new technology must be examined through the prism of gender equality. More generally it should be noted that only 17% of IT and communication specialists in the European Union are women. A lack of representation which translates, as in politics, into a lack of voice, and ultimately into a lack of consideration of the different forms of discrimination against women and an increase in sexist prejudice.

Improving women's status also means adapting policies towards men

Women's lives will not improve if those of men remain unchanged. This concerns the economic sphere, but also childcare, for example. Paid paternity leave is not currently provided for in all EU Member States. The directive on work-life balance for parents and carers, adopted in June 2019, aims to harmonise arrangements in the Member States by establishing a minimum of ten working days paternity leave for fathers. Importantly, the period of leave must be paid. Member States had until 2 August 2022 to transpose the Directive into national law. The text should therefore introduce paid paternity leave in the four Member States that do not currently provide for it (Austria, Croatia, Germany and Slovakia) and to extend paternity leave by a few days in six other Member States (Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands and Romania). Although this is a minimal gesture that concerns only a few days, progress in this area is slow and Member States are dragging their feet in transposing the Directive. On 20 September 2022 the Commission launched an infringement procedure, sending a letter of formal notice, against 19 states (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Spain) for insufficient transposition regarding parental or carer leave. In Germany, on 24 December 2022, the law transposing the directive came into force ("Gesetz zur weiteren Umsetzung der europäischen Vereinbarkeitsrichtlinie in Deutschland"). Even though political changes in support of men have been growing for the last few years, including at Member State level - with for example the extension in France in 2020 of the period allocated for paternity leave from a previous 11 to 28 days, or in Belgium which raised the same leave from three to four week on January 1 2023 much remains to be done. In general, the issue of men's under-representation in so-called care work, carried out within the family and in unpaid domestic work, needs to be raised to achieve true gender equality. Real policies and mechanisms to achieve this are, however, still too rare.

***

Every crisis strengthens the Union, but the risk of setbacks for women may increase. It is therefore crucial that socio-economic policies address gender equality in a holistic way so that women are not weakened in these critical phases. Moreover, the global context seems to be hardening and progress towards gender equality is currently taking too long; it is often not decisive enough to have a real and systematic impact on women's lives. Threats to the rule of law in some Member States must also be understood as threats to women's rights and the EU must respond. The European Union remains the region of the world where women live best. Moreover, important European policies are on the agenda or have come into force in recent years to ensure that discrimination against women in Europe is reduced and that new forms of discrimination do not emerge. However, there is still a long way to go, particularly at global level, but also in Europe. With its comparative advantage, the European Union must ensure that any obstacles preventing European women from moving ahead are removed, because ... their impatience is growing. And they are worth it! The author would like to thank Lina Nathan, Research Assistant at the Foundation, for her help.

[1] See Ramona Bloj, Women's Europe, Robert Schuman Foundation Policy Paper N°587, March 2021

[2] Lower or single houses

[3] According to UN Women extreme poverty is defined as living "on less than $1.90 per person per day."

[4] According to Eurostat, persistent poverty refers to "the population whose equivalised disposable income was below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold in the current year and in at least two of the previous three years".

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Fondation Robert Schuman

—

23 December 2025

Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

—

16 December 2025

Digital and technologies

Josef Aschbacher

—

9 December 2025

Democracy and citizenship

Florent Menegaux

—

2 December 2025

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :