Businesses in Europe

Olivier Perquel

-

Available versions :

EN

Olivier Perquel

Former head of Natixis's corporate and investment banking division, senior advisor at Ares Alternative Credit, member of the Foundation’s Scientific Committee.

At the end of the year 2025, all economic players agree that Europe's economic and financial situation is worrying, and that there are many issues at stake. However, it is no doubt worth trying to list them, by presenting a few figures, and highlighting some avenues for recovery, or a new start.

A growing productivity gap

Compared with its international competitors, the European economy is suffering from a growing productivity gap. Whereas GNP per capita was on a par with the United States in the 1990s, today it is 20% lower than that of the latter, and the main reason for this is the shortfall in labour productivity[1].

One of the main causes is the lack of innovation in European companies, particularly in the technological field. Spending on research and development, for example, represents 3 to 4% of turnover for large European companies, compared with 12% on the part of their American counterparts[2].

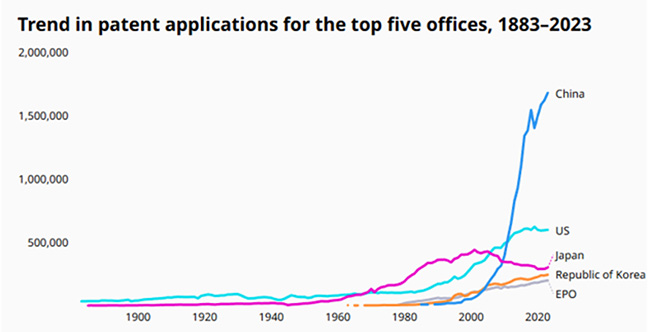

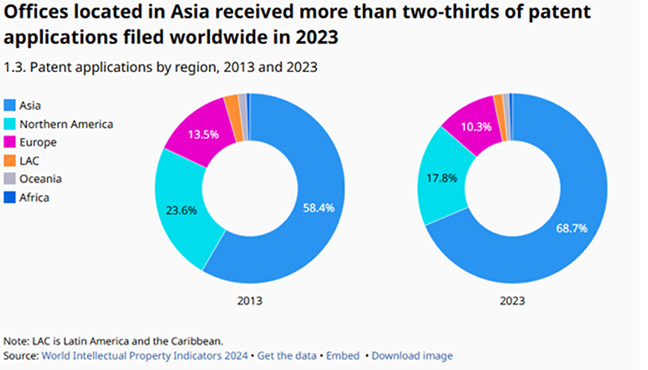

The gap is similar in terms of patent applications (69% in Asia, 18% in North America, 10% in Europe)[3]. Finally, public research is less well funded and less focused on technological innovation. Another illustration of this innovation gap is the shortage of start-ups, and a greater difficulty in growing them on our continent: there are fewer unicorns (private start-ups with a valuation of at least $1 billion) in Europe: 790 in the United States, 280 in China, 310 in the rest of Asia, 110 in the European Union and 65 in the United Kingdom[4]. Venture capital investment accounts for less than 0.2% in the European Union, compared with nearly 0.7% in the United States and 0.55% in the United Kingdom[5].

Patent applications by office, 1883-2023

Patents by office in 2023

Venture capital investments 2013-2023

(Average GNP percentages)

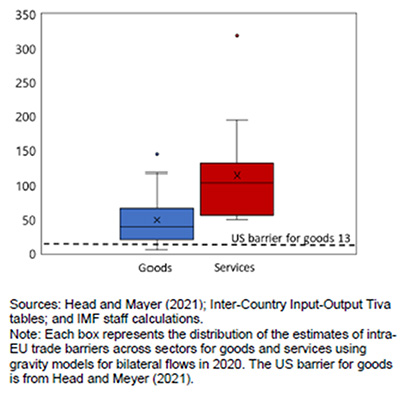

The second cause is the fragmentation of the European market. The intensity of trade between the 27 Member States is 40% of that between the 50 States of the United States, and trade barriers (restrictions imposed by administrations on international trade) are estimated at around 45% for goods and 110% for services. This represents an increase of 6% and 11% respectively since 1995, while barriers to trade in goods are 15% in the United States[6].

Intra-European Union trade barriers in 2020

One of the explanations for the level of trade barriers is European over-regulation, resulting in an explosion of standards and controls, with a major impact on productivity and lead times, and even simply on the ability to start a business or work. There are many anecdotal examples: the difficulty of reindustrialising or setting up polluting factories, the destruction of the European car industry, competition law preventing the creation of European champions like Siemens-Alstom, the ban on many areas of medtech in Europe, threats of withdrawal by the oil industry (ExxonMobil) because of legislation on sustainable development.

US tariffs and the fall in the dollar are further widening the competitiveness gap and will accelerate growth of the productivity gap if this situation continues.

Higher labour costs

Moreover, the European economy also suffers from higher labour costs. Tax and social security contributions are around 50% higher. The tax wedge on an average salary is 30% in the United States, 29% in the United Kingdom, 33% in Japan and 45% in Europe (48% in Germany, 47% in France) in 2024[7].

Tax wedge per country

(as a percentage of labour costs in 2024)

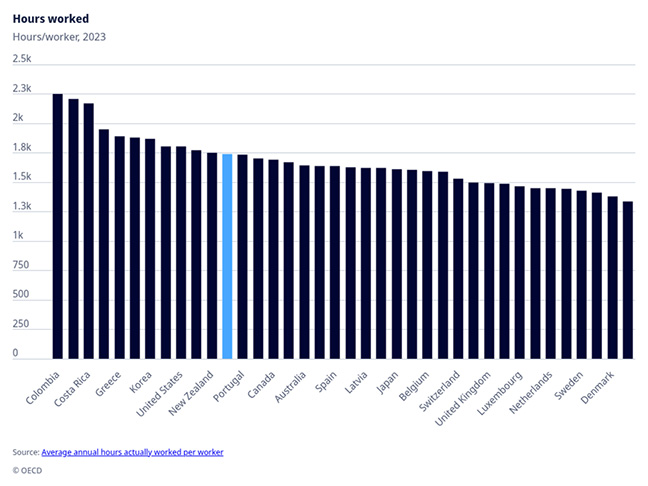

The hours worked is significantly lower in Europe: for 1800 hours worked per year in the United States, Germany works 1350 hours and France 1500[8]. The difference is even greater when we look at the total time worked over a lifetime: the average effective retirement age is 68 in Japan, 65 in the United States, 63 in Germany and 61 in France; finally, the unemployment rate is 4.2% in the United States, 4.5% in the United Kingdom, 3.5% in Germany, 7.6% in France, 6.7% in Italy and 2.5% in Japan[9].

Hours worked by country

The same applies to energy costs

Finally, the cost of energy, mainly due to the phasing out of Russian fossil fuels and the low use of nuclear power in the European Union, is 2 to 3 times higher than in the United States. Renewable electricity remains expensive, with wind power not performing as well as expected and solar power reaching a plateau. In fact, its intermittency and the lack of sufficient batteries mean that its production has to be compensated for by additional fossil fuels during off-peak hours, generating additional costs and undermining the ecological transition. The cost of electricity is 8 cents/KWh in the United States, 22 cents/KWh in the United Kingdom, 18 cents/KWh in Germany and France, and 17 cents/KWh in Italy. The cost of natural gas is 5 cents/KWh in the United States, 8 cents/KWh in the United Kingdom, 10 cents/KWh in Germany, 12 cents/KWh in France, and 13 cents/KWh in Italy[10].

Industrial electricity prices by country (2024/2025)

An insufficiently developed equity market in Europe

As a result, the profitability and growth prospects of European companies are lower than those of their American counterparts, and investment in them is less attractive. It is therefore not surprising that a large proportion of European savings are invested in the United States, while the reverse is much more marginal.

The US public and private equity market is 2.5 times larger than in Europe. Financial assets there represent $80 trillion, two-thirds of which is equity, while in Europe and China, they each represent $60 trillion, with one-third being equity[11].

This is largely due to the modest role played by mandatory funded pensions in most Member States, which results in pension funds being relatively small. In the United States, the ratio of assets to pension funds as a percentage of GDP is 170%. In the Netherlands and Denmark, the only European countries where funded pensions are compulsory, it is over 200%; elsewhere in Europe, it is less than 15%[12]. This is obviously the main source of savings that is thus absent from our economies.

But this can also be explained by the lack of appetite for risk on the part of individual European investors, influenced by European investor protection policies. Individual American investors spend 4 times their GNP in the economy via investment or private pension funds, whereas Europeans invest only once the amount of their GNP[13].

So, it comes as no surprise that equity financing is less available to European companies. Over the last 20 years, they have raised half as much as American companies. Similarly, start-ups have the greatest difficulty in raising capital in Europe beyond the Series B level (see data on venture capital investment). It is also interesting to note the advantage this gives American investment banks, which have been able to expand in Europe to an astonishing degree as a result: they take 40% of the commissions in Europe, and 70% on mergers and acquisitions and on the primary equity market (ECM).

It is also worth noting the absence of securitisation in Europe, which was largely blocked after the subprime crisis. The American market is 6.5 times the size of that of Europe. Finally, we should mention the new competition from private debt, again largely American, against European bank financing.

A structural disadvantage in terms of raw materials and rare earths

Another European challenge is that of raw materials, particularly rare earths and metals. Europe currently relies on Chinese imports for almost 98% of its mineral requirements[14], and since the 1980s China has been proactively structuring its “rare” mining industry in both extraction and refining. However, mining capacity exists elsewhere, and other countries such as Japan and Australia have adopted proactive strategies. In March 2024, the European Union adopted the European legislation on critical raw materials, which recognises its dependence on rare metals. In March 2025, an initial list of 47 European projects designed to strengthen European control over these value chains was drawn up. These projects cover the extraction, transformation, recycling and substitution of raw materials in Europe. However, these projects, which have major environmental consequences, are likely to come up against local resistance like the NIMBY (‘not in my backyard’).

Weakness in the face of tougher international trade

Finally, it will not have escaped anyone that the nature of international trade has changed in recent years. The era of happy globalisation is over, and international trade has entered an era of power struggles at best, and economic warfare at worst. American customs duties and GAFAM's attacks on European digital regulations are an American manifestation of this; the massive redirection of Chinese exports to Europe reflects China's response. China currently exports 16% of its production to the European Union, and 10% to the United States; just a few years ago, the reverse was true[15]. Faced with these two heightened risks, Europe's response is slow in coming.

Possible solutions

Possible solutions exist and have been clearly identified. However, these are long-term avenues that will require a sustained effort over several decades, and a return to genuine political stability and shared ambition.

The Draghi Report

The Draghi report lists the main ones: push innovation, adopt a new industrial strategy (taxes, trade and geopolitics), reform European competition law, finance investment (reduce the fragmentation of capital markets, finalise the banking union and relaunch securitisation), reform the European decision-making process by reducing the flow of regulation and simplifying ‘implementation’.

To boost innovation, the report recommends refocusing and stepping up the EU's framework programme for research and innovation, better coordinating public R&I between Member States, consolidating European academic institutions, improving the regulatory and financial environment for entrepreneurs, facilitating consolidation in the telecoms sector, and ensuring the maintenance and expansion of public R&I for key manufacturing sectors such as pharmaceuticals.

In terms of industrial policy, the report details its recommendations in ten sectors: energy, critical materials, digitisation and advanced technologies, energy-intensive industries, green technologies, the automotive industry, defence, space, pharmaceuticals and transport.

The report also recommends better planning for decarbonisation, combining industrial planning, particularly in the renewable energies and automotive sectors, with an aggressive policy to strengthen security and reduce dependence on critical metals.

Funded pension schemes

In addition to the creation of a single financial market, the introduction of mandatory funded pensions in all Member States is, in our view, an essential tool for rebuilding Europe's financial capacity. In 1997, Canada set up a public system based on independent governance and in-house management of more than 50% of assets. In 25 years, assets under management have jumped from 34 to over 600 billion Canadian dollars, 75% of which is invested in the real economy. In 1992, Australia introduced a compulsory occupational ‘superannuation’ scheme that allows employees to pay part of their remuneration into their superannuation fund, while benefiting from a favourable tax regime. Today, the majority of Australians save via their occupational plan, which represents more than AUD 2300 billion, 75% of which is also invested in the real economy. It took ‘only’ 30 years for these two countries to set up this essential tool to finance the real economy. In Europe, a number of timid attempts are being made, such as France's retirement savings scheme. But a clearer political will needs to emerge.

Reciprocal protectionism?

China's systematic and aggressive use of forms of protectionism: dumping, massive subsidies, access to public procurement markets, and control of foreign investment; and the massive American return to this, mainly through customs duties requires a more effective response from the European Union. Various tools and procedures exist, and their effectiveness must be strengthened, but in this area too, Europe must above all find a more consistent, unified political will for automatic reciprocity. The preponderant size of the European market undoubtedly gives the Union real room for manoeuvre, both in terms of negotiating capacity and in terms of more systematic implementation of existing measures or “implementation” of additional protective regulations. As far as the United States is concerned, the current choice of compromise will not withstand the next U.S. phase, even if there is a real possibility that tariffs will collapse of their own accord as a result of political developments in the US or domestic legal constraints.

At Member State level

And there are also many avenues for recovery at national level: generalising supply-side taxation, or even standardising European taxation, dealing with budget deficits in Europe, particularly in the South, harmonising social security systems and developing funded pensions (creating pockets of additional capital and reducing the growth of social security system deficits), returning to nuclear power, etc.

***

There is nothing to indicate that the people of Europe are ready for this change in approach, or even for this leap of faith. But it must do so, otherwise the 21st century, which has already witnessed the return of empires, could well also be the century of new colonisation, for which Europe, like Africa for that matter, would pay the price.

[1] IMF, Regional Economic Outlook Europe

[3] World International Property Organization

[4] Visual Capitalist website, Crunchbase

[6] Head and Mayer 2021

[7] OCDE tax wedge

[11] IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, remarks on strategic priorities for the European capital markets, 15 June 2023 and after the Eurogroup Meeting 19 June 2025

[12] FMI and Federal reserve of St Louis

[14] ‘La guerre du métal’, Jean-Wilfried Diefenbacher, published by Hermann, October 2025.

[15] ‘La dette sociale de la France’ Nicolas Dufourcq, published by Odile Jacob October 2025

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

Strategy, Security and Defence

Jean Mafart

—

27 January 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :