Franco-German

Grégoire Postel-Vinay

-

Available versions :

EN

Grégoire Postel-Vinay

At this, the start of the year the Union faces two imperatives which is causing a great amount of activity: the need to aid recovery with competitiveness policies which can stimulate growth and employment, as well as the need to settle concern about sustainable development which is reflected generally in many issues on agenda 21 and which focus on the question of energy transition (ecological transition includes energy transition but cannot be summarised by that alone: the assimilation of these notions does not take adequately on board the deterioration of some parts of our eco-system, which has occurred faster and been more evident than that of raw materials, for example the problem of the world's food production capacity). All of this is occurring in a context in which, since the second war in Iraq and with the rise of the emerging countries, the rise in energy prices, governed by the cost of hydrocarbons, has meant that the Union has spent more than 1000 billion additional € on its energy imports (the EU imports 60% of its gas and 80% of its oil; its coal imports have been growing since the US are selling more); this weighs on growth and at the same time forces the EU to increase its exports so that it can cover these additional costs. Hence whereas energy issues were important during the reconstruction of Europe and were the origin of the ECSC and then Euratom, with energy transition they have now become pressing once more.

These concerns have led to policies in the Union and the Member States: title XXI of the Lisbon Treaty is devoted to them and they have been addressed by four European Councils. The Council of March 2007 set three priorities: competitiveness, climate change and energy supply security which were transposed into legislative terms (3rd "internal gas and electricity market package", oil and gas supply security, review of the directives on building energy efficiency, and the labelling of energy associated products, eco-design) via strategic guidelines (the 20-20-20 energy-climate package by 2020). The meeting of 2011 defined the energy strategy, by listing mid-term priorities for 2020 on the one hand (infrastructures, research and innovation, energy efficiency, internal market, internal production, external relations) and on the other it noted that these issue involved long term, and even extremely long term investments (buildings, infrastructures) and therefore they speak of perspectives up to 2050. The May 2013 Council insisted on the need for sustainable energy supplies at affordable prices, and that of December 2013, noting the need to increase electricity grids if renewable, intermittent energies are developed, insisted on European interconnections.

Two new dates have now emerged: the European Council of 2014 will address both industrial and energy policy which illustrates how interlinked these two issues are. It will also take place in view of the 21st climate conference at the end of 2015 in Paris. At the same time national strategies taking on board each country's specific nature are being drafted, which in the light of the production and consumption of energy and their articulation on more local levels, have very different requirements. What are the main issues at stake now? To understand these, a world analysis is necessary, and possibly a declension of its consequences for Europe and its Member States. Secondly we have learnt from recent experience - which of course has been atypical because of the crisis but which reveals several factors suggesting that the policies undertaken can be perfected, that three goals have not been achieved: the Union's energy dependency is growing, unlike that of the USA, its goals to reduce greenhouse gases by 2020 will probably not be achieved, and energy prices are growing sharply in the Union, thereby straining household buying power and demand, and also industry and services' production costs. Without pretending to be exhaustive this paper will address issues pertaining to governance, international negotiations, the Union's energy autonomy, competition, technical progress, energy insecurity, specific national factors, tariffs and production, and their effects on infrastructures and supply security.

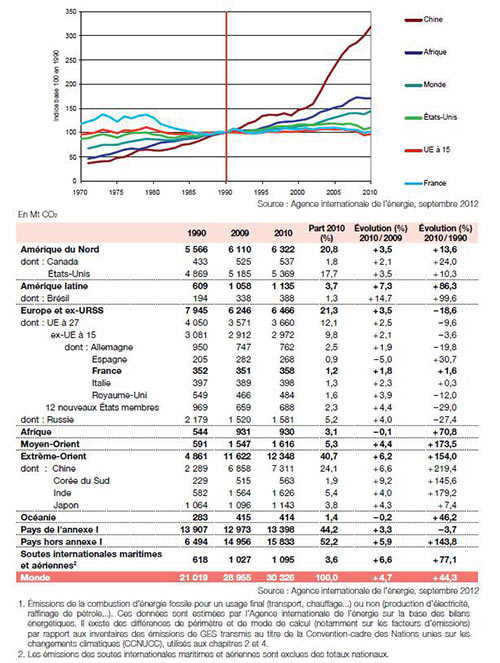

On a world level - the question of greenhouse gases

Since the Stern report world summits have succeeded one another. However they have not led to a clear reversal in the general trend, carried along by demography and the impetus of the emerging countries, of increasing greenhouse gases. The landscape is extremely contrasted however: in 20 years Russia, especially due to its collapse during the 1990's, has reduced its emissions by 27%, the European continent (including Russia) by 18.6% (and over the coming decades its contribution to greenhouse gas emission will be below 15% of world emissions), the EU has reduced them by 9.6% and its share in world emissions was only around 12% in 2010 whilst Japan's emissions have increased by 7%, North America by 13.6%, Africa by 70%, Latin America by 86%, the Middle East by 173%, Asia by 154%, including India 179% and China, 219%. The Far East alone now represents more than 40% of emissions and by 2050 this share is due to rise even more and will be more decisive for the planet than all of the previous centuries put together.

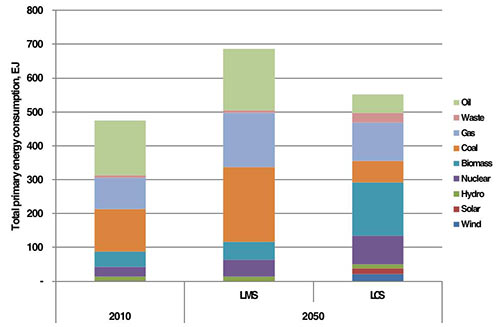

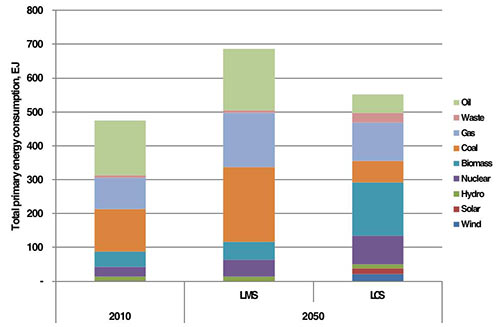

Regarding demand, studies, like the extremely detailed one by the Imperial College of London in 2013, illustrate scenario without concerted action (Low Mitigation Scenario-LMS) or with concerted action (Low Carbon Scenario) thereby modelling possible developments for 2050 (without prejudice to possible improvements brought by technical progress), hence some structuring details emerge.

Primary Energy in 250 according to two scenario (Imperial College)

Primary Energy in 250 according to two scenario (Imperial College)

Final Energy Consumption according to two scenario (Imperial College 2013)

Final Energy Consumption according to two scenario (Imperial College 2013)

Nine stylized conclusions emerge:

- The climate challenge can be overcome to a cost of around 1% per year of global GDP by 2050 in investments;

- Presently known technologies enable this without prejudice to the improvements that might be provided by innovation and R&D;

- No solution is possible without a significant increase in the share of electricity in the world energy mix and that this share comes from decarbonised sources; the low carbon scenario includes both major energy savings and a two-fold rise in world electricity output by 2050. This is a vital condition in the scenario, in which annual CO2 production is reduced from 32 billion tonnes at present down to 16 billion in 2050 i.e. that we limit global warming, in the light of current knowledge, to 2° in 2100.

- All solutions for electricity will have to be decarbonised: renewable sources with an overall supply involving the simultaneous production of alternative energies to compensate for the intermittence of some of them (solar, wind), the capture and storage of the carbon produced by these alternative energies (gas, coal, oil, biomass etc ...) and the retention of nuclear resources. But also the share of the use of electricity in transport has to increase.

- On a world scale the share of biomass and the recycling of waste in renewable energies will be preponderant;

- The chances of rising to the climate challenge firstly depend on the goals defined at the G20 level at least, of CO2/kWh emission ratios and CO2/km run by vehicles, and more generally of the effort made in the design and modernisation of our towns to turn them into smart cities (major agglomerations aggregating a major share of the population) ;

- Industry and services will play a major role in energy transition both through their new offers and as consumers. Moreover we should note that in the 20th century the world population tripled in size, the GDP rose 20 fold, fossil energy consumption by 30, industrial activities by 50 in volume. Again these consumptions only involved slightly over one billion people. Although services occupy an increasing share in the GDP, requirements in terms of physical goods will still rise in the 21st century, thereby making efficient use of non-renewable resources and increased efforts in terms of recycling all the more necessary.

- Hydrocarbon producing countries may have an in interest in oil prices ranging from 75 to 110 €/barrel (in terms of present €/$ parity) and yet still overcome the climate challenge;

- Hydrogen could be amongst the new sources of energy to improve productivity in the manufacture of synthetic fuels and also for the storage of renewable energies when there is a surplus.

These initial conclusions provide some suggestions for governance and diplomatic priorities.

Governance:

Because of their nature, energy and environment related subjects, like those related to competitiveness affect all human activities. In order to take balanced decisions, skills involving economic analysis, R&D devoted to the relevant technologies, analysis of the effects on employment, housing, transport, urbanism, industry, services and agriculture, implications for defence and security and international negotiations have to be brought into play. This supposes steering which takes on board all of the societal issues at stake and prevents those bodies in charge of the legitimate problems that emerge from operating in silos. The prospect of a new Commission and European Parliament provides an opportunity for thought about this. Of course the same applies to the Member States whose internal arbitration will take differing starting points into consideration.

International Negotiations:

Secondly from the point of view of reducing greenhouse gases - a global problem - Europe cannot play a totally effective role by just taking decisions for itself. It has to influence its partners - as they influence it-, or continue the global trajectory as seen in the statistics. The bid to shape additional effort for its partners' agreement has already been tried in vain. Concerns of domestic order prevail and additional effort - even significant on the part of the Union, would be but marginal in view of the developments witnessed in other regions of the world. In addition to this unilateral commitments, in the event of sufficiently adequate mechanisms not being simultaneously set in place to prevent the relocation of energy-intensive activities, would also increase global greenhouse gas emissions via the relocation of these activities to less restricted areas and via the transport costs thereby incurred; this would lead to unemployment and the loss of value added in Europe. The best way to prevent this phenomenon would be to achieve an international, binding agreement, both universal and ambitious, expressed in commitments followed by reductions in greenhouse gases in all of the countries involved. Without this a carbon border adjustment mechanism would be necessary, which has already been planned for as an option by the legislation in force. Hence conditioning the pace of European commitments to significant commitment on the part of its partners would encourage a virtuous process. We must therefore send out a pro-active message and at the same time, and not successively, negotiate its implementation as part of the preparations for the Paris Summit.

We must also bear in mind that the investments required worldwide will be all the more effective if each euro, dollar or yuan is invested where emission reductions are the most efficient. In this regard in 2013 we see that China approved the construction of at least 15 major coal mines, capable of producing 100 million tonnes and more and that Germany increased its production of greenhouse gases in spite of its renewable energy programme, due to the need for other means of production when intermittent renewable sources were not available, and also due to tariffication that has led to the substitution of coal fired installations with those running on gas.

It follows that work devoted to improving techniques in Europe, whether on a national or European level, via pertinent chapters in the H2020 programme, must explicitly include an international chapter for the sale of products and services to those countries which produce the most greenhouse gas, taking on board their specific nature, which is often different from that which prevails in Europe.

This also means that monitoring would have to be undertaken to check labelling on products in terms of their energy content and the energy consumption they cause, including those imported into Europe.

It also follows that as far as consumption sources are concerned, which are mobile by nature, only international agreements will be really effective. Hence, for example, the achievement of an agreement within the international maritime transport organisation to improve ships' energy efficiency and to limit their CO2 emissions is vital if we want to both improve energy efficiency and maintain fair competition in the world economic sector.

Finally it follows that the goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 and by 60% by 2040 - in line with its long term goal to divide its greenhouse emissions by four by 2050, which the Union has to set itself in regard of its ecological goals - must include a conditional element for the achievement of an international agreement which provides for firm commitments in 2015 in order to protect the EU's negotiating position and the competitiveness of our businesses in contrast to third countries since the goal of competitiveness is just as important. Setting a goal for 2030 will also improve the strength and the credibility of the emission transfer system (ETS) which is weak at present, (as shown by the volatility of CO2/tonne prices), as it sends out the pertinent signs to market players. Other international aspects will be discussed concerning grids and supply security.

What level of energy independence in the Union?

A third series of questions addresses the Union's energy independence and the strategies followed by other major regions in the world: hence the USA have developed their strategy which, to date, has focused on the mastery of world resources towards greater autonomy based on innovation and the more intensive use of their own natural resources. The first has given rise to an extraordinary appearance of new solutions which is continued with renewed effort in terms of R&D and greater links between digital technologies and energy problems (smart cities, vehicle piloting etc ...); the second has led to drilling for shale gas or non-conventional hydrocarbon resources, (that has gone together with a reduction in coal prices and an increase in their export, notably towards Europe), which has brought it to an almost autonomous situation in terms of energy.

As far as China is concerned in the 12th plan we can see that efforts are focusing on further energy saving and rational energy use, rapid growth of renewable energies and nuclear power, projects focusing on 193 smart cities and greater import flows of energy sources from third countries. In February 2014 the Council for State Affair's Centre for Research and Development declared that China's energy policy priorities for 2030 should be energy security, the respect of the environment and energy efficacy. Based on the work of several dozen international experts the Centre is trying to anticipate the effects of China's increasing dependency on international markets (75% of the oil used in China in 2030 would be imported) and is calling to provide more space on the markets in the area of energy in line with the guidelines defined during the third plenum of the 18th Central Committee. Emphasis is also being placed on the need to build compact cities to limit urban sprawl and to reduce the flow of associated transport whilst 65% of the population might be living in towns by 2030.

On a world scale the OECD countries are not the decisive ones: overall energy consumption growth in the EU is less than that worldwide. 60% of consumption increases forecast by the IEA in its recent long term scenario come from China, India and the Middle East. Qualitatively these increases govern the position of coal and the main developments in world and regional flows of oil and gas.

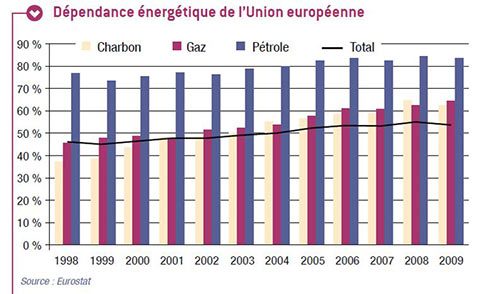

In the meantime Europe is witnessing a rise in its energy dependence, governed by the dual phenomenon of a reduction in its internal production capacities and an increase in its demand for coal and hydrocarbons, linked in part to world coal prices, and also to the overall internal demand or the increased share of intermittent renewable energies, whilst the issue of storage and increasing the interconnection of grids has not been completely resolved.

Hence the European Union's energy dependency totalled 53.8% in 2011 against 47.4% in 2001. The gross internal consumption of primary energy in the Union totalled 1,697 billion toe in 2011, the year when it imported 939.7 Mtoe. It imports more than 80% of its oil requirements - whose price has tripled in 10 years - more than 60% of its gas and coal requirements. Concomitantly the decline in its production of primary coal, lignite, crude oil, natural gas and more recently nuclear energy has meant that the Union is increasingly dependent on other countries for its primary energy imports to satisfy its requirements.

However should dependency be feared? We know what the arguments are: short term the optimisation via best market prices wherever the resources come from, maximises the creation of value. To this there are long term counter arguments: greater competition from several regions in the world for access to rare resources like fossil energies is a potential source of conflict; over dependence on the resources of a third country might enable the exporting countries to influence the strategy of those importing (the present case of Ukraine being typical in this situation); the profit created amongst those exporting gives them the capacity to purchase many assets, extending in some cases to strategic control (oil profits provide 800 billion $/year to exporting countries); rapid fluctuations in the principal market, which the oil market is, affect consuming industries, whilst, if they have drafted processes that depend on sources that are relatively insensitive to market fluctuations and at the same time remain competitive they enjoy, on the contrary, a structural advantage for their competitiveness and employment; finally dependency on imported resources makes the equivalent production in exportable goods and services necessary, at the risk of impoverishment and debt. The Union devotes 2.5% of its annual GDP to energy imports; in 2011 the oil bill totalled 270 billion € and the gas bill 40 billion €.

As a result it is important to at least have indicators to show dependency levels and to act according to what public debate reveals to be the optimum; it also follows that recently developments have not been positive and call rather for greater independence long term.

The Impact of the Competition Policy

We should note that the question of energy autonomy is not separate from the Union's competition policy. This has been positive due to the increased dynamism required on the part of the various operators. It can also be negative if it works against long term contracts which are sometimes necessary for heavy investments that are paid off over long periods of time and whose risk level supposes stabilising mechanisms; indeed in this case only "light" investments are made which mainly involve gas or more costly examples and in the end which encourage the import of hydrocarbons into the Union. This is important just as the Commission deems that nearly 1000 billion € have to be invested in the European energy sector by 2020. The case of the British EPR will be significant in this regard and the Commission might not be advised to give further reason for the separatist trend on the part of the UK to prosper. From a general point of view long term electricity and gas supply contracts mean that investors enjoy the visibility necessary for major projects.

More generally the review of the Community's management of State subsidies, notably those pertaining to R&D and innovation, should refocus monitoring towards those which create the greatest distortions on the internal market. And the ongoing review of State subsidies will not endanger energy-intensive industries, since it takes better account of the global dimension of the issues at stake and employment in Europe.

Technical Progress

The main EU Member States, have like the USA, been undertaking R&D into energy, seen as a leading strategic issue. In this domain, especially over the last twenty years, the EU has been breaking through, notably with guidelines in the R&D "H2020" programme which clearly strengthens the share devoted to energy: 5.9 billion € by 2020 in the part devoted to safe, clean, efficient energies and 2 billion € for Euratom, which reflects one of the five declared priorities for 2010 as a strategy for competitive, clean, safe energy (energy efficiency, internal market and infrastructures, consumers and safety, research and technology, external dimension). There is also the 2030 energy-climate package put forward by the Commission in January 2014. Of these funds 85% are being granted to research into non-fossil energies and spread across three major themes: energy efficiency, low-carbon technologies, smart towns and communities. The whole is subdivided into many parts: carbon capture and storage, intelligent grids, land and off-shore wind farms, 2nd and 3rd generation biofuels, geothermal energy, hydrogen technologies, and fuel cells, bio-energies and technologies for the storage of various energies. Moreover complementarity with other parts of the Horizon 2020 programme, notably in transport and digital technologies and Euratom are involved in the R&D into fusion, fission and radiation protection. All of this is a major tool for more effective action undertaken on a European level which will take better account –better than it has been to date - of the strategies adopted by each country and from a more optimistic standpoint, to improve how they function together. These investments may also help to maintain and improve the world rank held by European businesses in both conventional and renewable energies. It may also help their leadership in the area of nuclear energy and electrical equipment before and after the meter.

However this work is only marginally oriented towards measures applicable outside of the Union and will only benefit its businesses whilst it will not be the main contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, nor the main consumer by 2050. Changes might be provided to ulterior phases of the programme in the light of results of the Paris Conference.

Energy Insecurity

The economic crisis has left many Europeans in a state of insecurity linked to access to energy, which can weigh heavily in the budget of poor households. In 2010 the European Parliament deemed that this insecurity - according to varying modes of assessment - often arises when energy represents more than 10% of household spending and that this affects between 50 and 125 million Europeans. The effects of energy insecurity are multiple: they affect employability negatively, likewise health, growth and energy consumption itself since poor housing is rarely renovated to improve insulation. The main means to address this are legislative (conditioned preferential tariffs), or incentive based (the FEDER finances the energy improvement of housing in all Member States in principle).

Specific national, tariff and production features and their effects on infrastructures and supply security

Energy mixes, that is all of the factors involved in production, vary greatly from one Union country to another, which for a long time has limited the scope of the energy policy planned for Europe. This is still a reality and means that the goals set on a community level allow Member States a great deal of flexibility regarding how they are implemented.

Energy policy is vitally dependent on price signals. Just two examples which match nearly half of the European GDP illustrate this. The French and German situations are extremely different from the point of view of tariffs: in Germany households bear the burden of subsidies granted to its renewable energies (to a total of around 20 G€/year at present) whilst its businesses are exonerated. To date France has privileged light tarification on its households providing them with the benefits of the surplus created by its nuclear fleet. If there were to be a sharp rise in tariffs this would affect growth negatively since household purchasing power would be affected, whilst right now, France is being forced, in terms of salaries, toward moderation in order to prevent the relative drift experienced in comparison with Germany over the first decade of the century. Raising tariffs applied to businesses, particularly electro-intensive industries would be disastrous in both countries and would encourage off-shore investments rather than create jobs in Europe. In France where margins are low this would damage opportunities to be taken in the world recovery and in Germany it would damage exports. It follows that focus must be placed on electro-intensive issues and carbon prices including European imports.

More generally with extremely low inflation in Europe the rapid rise in energy prices suggests that other areas of economic activity are following deflation and its detrimental effects on investment and employment in several Union countries. This calls for new solutions to be developed, not only according to reduced energy consumption, but also reduced production costs. Since the other argument is that as energy import costs are rising, European industry and services must be efficient and export more, which again means the control of energy costs that have to be a vital component of Member States' and the Union's energy policies.

Regarding consumption fossil energies represent 78.8% in Europe where they are preponderant, as elsewhere in the world: oil takes first place in the energy mix, followed by gas, whose share has risen over the last fifteen years and coal whose share was decreasing, but which is now rising again because of low American prices.

Regarding production, nuclear materials are the first source of primary energy in the Union, ie 28%, involving 17 Member States, but the spread is heterogeneous: France alone represents nearly half of European consumption and the UK a major share. Then we have coal (20.8%), of which Poland and Germany are the main producers, renewable energies (20.3%), gas (19%) and finally oil (12%).

One of the effects is that diversity almost mechanically leads to infrastructure requirements for the transport of energy: hence the Commission believes that half of the investment requirements in energy by 2020 i.e. 500 billion € are required in transport infrastructures. The EIB could help finance these.

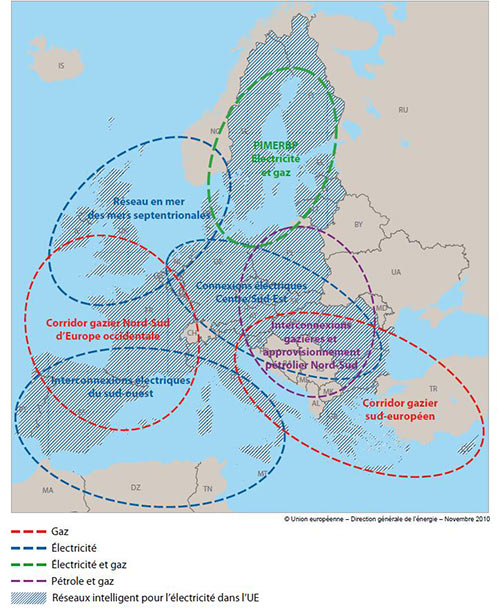

The densification of infrastructures also matches a concern for intra-European solidarity in terms of supply security: the regulation governing energy infrastructures adopted on 21st March 2013 provides for the financing of 12 priority corridors for the Union with a focus on security and solidarity between Member States, as expressed in article 12 of the Lisbon Treaty: "Without prejudice to any other procedures provided for in the Treaties, the Council, on a proposal from the Commission, may decide, in a spirit of solidarity between Member States, upon the measures appropriate to the economic situation, in particular if severe difficulties arise in the supply of certain products, notably in the area of energy." Moreover chapter 6 of the Euratom Treaty provides that nuclear supply security be guaranteed by the common supply policy implemented by the Euratom Supply Agency. And the need for a European energy strategy including geostrategic analyses, appropriate diplomacy, the upkeep of a diversity of source supplies also contributes towards this security via infrastructures, (gas pipelines, electricity grids around the Mediterranean, the Caspian, gas resources in the Eastern Mediterranean etc.)

The issue of grids and tariffication is also related to the development of intermittent energies: in France the transport network manager notes that a lack of capacity will emerge in 2016 and other countries believe that the wholesale price of electricity does not remunerate sufficiently existing leading edge installations, nor does it enable further investments, production or reductions in consumption. Other European countries have nearly suffered blackout. The difficulty notably lies in the need to price the intermittence of the energy sources. Also the contribution made by major flexible consumers, like power intensive groups, to the balance should be acknowledged and we should learn from this in terms of valuing their capacities in order to foster their upkeep long term in the Union.

Conclusion

Europe is facing a triple challenge: geopolitical, regarding its position to influence the world; economic, regarding the performance of its industries and services to go with the nascent economic revival; energy and environmental, in a context of energy dependence and climate change. Rising to this challenge means undertaking a great number of both public and private actions, which should be coordinated and yet allow for sufficient subsidiarity that takes on board the diversity of situation in the Member States. Three factors can respond to this challenge: the European Council in March which is addressing industry in a timely manner, competitiveness and energy, the prospect of the renewal of the European Parliament and the Commission and the Paris Conference on Climate. Significant improvements might result from the way they are managed and the leverage they achieve over the Union's partners: we should know how to seize these opportunities and send out a message of hope which is necessary for cohesion and durable peace.

The present article does not engage the opinion of the institutions to which the author belongs.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :