supplement

Emmanuel Sales

-

Available versions :

EN

Emmanuel Sales

Chairman of Financière de la Cité.

Introduction

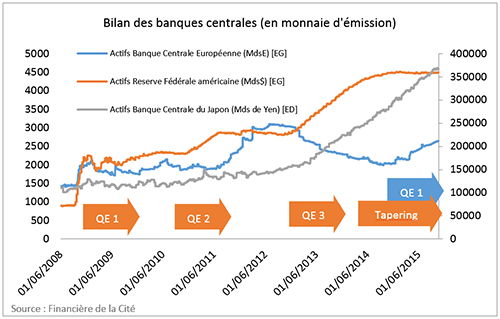

The financial crisis led to unprecedented action on the part of the central banks: the Fed increased the size of its balance sheet by six; the BoE, the BoJ and then rather late on the ECB launched similar policies. The financial system was rescued, intercession on the part of the central banks helped prevent the developed world plunging into a depression similar to that of the 1930's, with a loss of confidence, savings withdrawals, contraction in trade, bankruptcy of businesses and banks.

The extent of the central banks' intercession led to concern on the part of proponents of monetary orthodoxy and amongst amateurs of the Austrian school. However QE policies bear an inherent paradox: in spite of action by the central banks, growth has not been recovered; inflation is at its lowest ever level, debt has increased, whilst a liquidity glut has led to breakpoints across an entire swathe of financial assets. The central banks seem therefore to be in deadlock: the normalisation of monetary policies is capped by the dangers of economic collapse or debt-deflation - conversely, the upkeep of QE and low rates weighs on recovery and depresses activity. How can this vicious circle be brought to an end?

The continued expansion of the central banks' balance sheets will be a major stake in government policy for years to come. The "virtuous" end of QE, with a progressive normalisation of monetary policies and a reduction of the debt, is unlikely. In these conditions we have to look into the possible adjustment variables of QE policies (increase in interest rates, renewed rise in inflation, general restructuring of government debt, the taxation of savings, increased competition between monetary areas, etc.) and the ways of preparing for it.

To address these issues I shall describe QE mechanisms and at the same time, a certain number of preconceived ideas will be eliminated. Secondly, I shall take stock of the QE policies undertaken by the main central banks. Finally, a third part will be devoted to the conditions necessary for a return to normal monetary policies.

I. Description of QE policies

"A national bank must be tight when everyone is giving money away ... but when the crisis arrives it must be brave enough to give money to trade" (Thiers).

The philosophy behind QE policies lies in the continuity of the purpose of a central bank as they were defined at the turn of the 19th century: to provide struggling financial establishments with liquidities, provide markets with liquidities when trade is in danger of seizing up, to support confidence [1]. The central bank, as described by Bagehot in his book Lombard Street, is a reserve bank, and only secondly is it an issuing bank: it cannot act like a deposit bank, it has to ensure an issue margin so that it can withstand any waves of panic, i.e. limit discounts in normal times and provide liquid assets to the market when lending becomes more difficult [2]. It is the traditional "open market" policy that leads to the support of business via inflows of cash in times of waning confidence, with all of the associated dangers of collusion and quick gain for market operators close to the central bank, mechanisms that were described by the economist Cantillon in the 18th century.

QE policies, however exceptional they might be, are therefore part of the rationale behind the action undertaken by the central banks. They stand apart however, due to their scale and the nature of the techniques employed.

A. The mechanism: an increase in the base currency

In a system of flexible exchange rates the key rate is sovereignly defined by the central bank according to its interpretation of the economic and financial cycle within the remit granted to it by the authorities [3]. The central bank is supposed to select a relatively high interest rate when inflation is beyond target, or when the economy seems to be overheating and reduce its key rate in the opposite situation. This the traditional framework of modern monetary policies as set out by the economist Taylor in the rule bearing the same name.

However there is an absolute limit to the reduction in interest rates since the public can choose to retain savings in the bank or in the shape of cash. When interest rates are close to zero the central bank has no means of action to support activity and price levels, unless it envisages "fixed-demurrage currencies" or the taxation of cash savings [4]. In this case its only solution consists in providing liquidities to the market in the shape of the purchase of a certain number of long-term assets, notably government securities. This is the rationale behind quantitative easing.

QE is an operation whereby the central bank purchases assets in view of increasing its monetary base. This aim is perfectly set out by the Bank of England: "QE is an operation that concentrates on the quantity of money: the central bank purchases a certain quantity of assets financed by the creation of the base currency and an increase in central bank reserves" [5]. QE is therefore clearly different from traditional discount operations (or credit easing) which aim to re-establish a market's liquidity by providing liquid assets in exchange for commercial paper that is due to for relatively short-term reimbursement. Hence in theory, in the case of QE, any type of asset can be used as collateral to increase the central bank's balance sheet. Ben Bernanke, when he was chairman of the Fed declared: "in a strict regime of QE the aim of monetary policy is to increase reserves, which are the central bank's bonds; the composition of the loans and securities entered on the assets side of the balance sheet is accessory." [6] Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, a former member of the ECB Board of Governors supports this: "when a central bank decides to expand the size of its balance sheet, it has to select which type of asset to buy. In theory it can purchase any type of asset from whoever it likes." [7] Hence QE quite naturally goes hand in hand with qualitative easing, which leads to a deterioration in the quality of the assets acquired by the central bank as a representation of its monetary base. In practice however central banks purchase politically neutral assets deemed to be the most liquid, i.e. government bonds.

QE does therefore have a direct effect on the quantity of currency and on desirable deposits. Economic agents selling the assets acquired by the central bank (mainly pension funds, insurance companies, investment funds etc.) find that they are holding more liquidities than they would have in an ex ante situation. In this way they are encouraged to diversify their portfolio, by purchasing for example, private bonds or stocks, which reduce the cost of capital for businesses and stem the contraction of activity.

This presentation of QE helps correct a certain number of preconceived ideas:

QE's primary goal is not to reduce interest rates. When a central bank purchases government bonds it substitutes default or interest rate risk assets with monetary reserves and deposits that are not default prone but which are open to inflation and exchange rates. The reduction in interest rates results from operations undertaken by economic agents, with the risk of creating accumulation and breakpoints, as at the end of April 2015 on the euro zone markets;

QE is not free money for the banks: the excess of reserves caused by QE does however correlatively increase bank deposits. Banks play the simple role of intermediary in the operation and they cannot "lend" additional reserves to the economy;

In theory the Central Bank can expand the size of its balance sheet indefinitely, the only impediment being public confidence in the State's credit. Unlike the country's other economic operators the central bank can function, in theory, with negative capital, in that it can recapitalise eternally by the creation of money. The central bank does not have to worry about its "solvency". The ECB is however in a different situation, given the monetary culture handed down to it by the Bundesbank, which means it will defend an imaginary convertibility of the euro [8].

With this presentation now complete we must look into how QE policies have been applied by the various national central banks since the start of the financial crisis.

B. Different policies according to the specific features of each monetary zone

Originally designed to prevent the collapse of lending in the weeks that followed the demise of the Lehman Brothers, as of 2010, QE became a general monetary policy tool which set out to counter deflationist trends in the economy. Asset purchase policies were therefore reflected in an unprecedented expansion of central banks' balance sheets, with each institution acting according to the specific features of its own monetary zone.

The Fed and the BoJ, which are traditionally lenders of last resort, dating back to the management of the banking crises of the 19th and 20th centuries, stepped in as soon as the financial crises worsened in November 2008, as they stood as counterparties for banks in difficulty and by rapidly expanding their size of their balance sheets - firstly helping banks and building societies (2008-2009), and then by preventing their economies from deflating (2010-2013). The BoJ kicked into action in 2010 following Shinzo Abe's entry into office. During this period the ECB limited its intercession to support operations to the bank sector and to declarations of principle (the famous, "whatever it takes" declared by Mario Draghi in July 2012). The effective implementation of QE by the ECB only happened at the end of 2014 when the Fed reduced its purchases of government securities (the famous "tapering") and prepared the market for a tightening in its monetary policy. Therefore there was joint action by the central banks to relay each other in the provision of liquidities to the market. (cf. chart 1).

European Central Bank Assets (Bn€)

European Central Bank Assets (Bn€)American Federal Reserve Assets (Bn$)

Central Bank of Japan Assets (BnYen)Source : Chart 1

In the specific rationale of QE securities purchase operations go together with a wide range of assets. Although the Fed's activities extends to a wide range of securitization instruments (MBS, RMBS, etc.), the activities undertaken by the BOJ and the ECB firstly focused on the banking sector which represents the main source of financing the economy in both Japan and continental Europe [9].

II. What are the results?

It is still too early to take stock of these policies which might have to be prolonged indefinitely. By committing to a massive purchase of assets in 2008 the Fed certainly prevented the developed world from plunging into a major depression. However eight years after the start of the financial crisis and a range of monetary support programs, growth has still not recovered its pre-crisis level and debt has grown. At the same time asset bubbles have formed. Finally the risk of economic relapse, in a world with greater debt than in 2008, makes it difficult to normalise monetary policies. Although QE has not led to over-inflation it has deeply disrupted price formation on the financial markets, since it has created the conditions for an even more serious financial crisis.

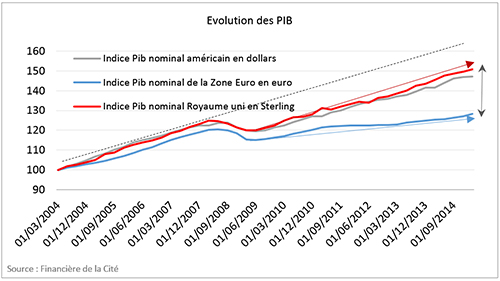

A. An effective tool to end the financial crisis

As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard [10] remarked regarding the economies that acted promptly and with the necessary vigour, the experiment with QE has been a positive one. The purchase of government bonds by the Fed did not lead to any further debt in the US, since the increase in the government debt was set off by a reduction in private debt. The American budgetary deficit is now declining, unemployment has fallen sharply, American growth has recovered its pre-crisis trend (without making good the gap in the former trajectory). Of course, the recovery of the US economy is not just due to monetary factors alone. There are other variables: the flexibility of the American economy, the rapid restructuring of the banks, the boom in shale hydrocarbons and the re-industrialisation of the American territory. QE policy undertaken by the British authorities also helped end the crisis, even though this has gone hand in hand with a larger trade deficit and a contraction in investments. London's role as a trade and financial centre has grown. Moreover, without the rapid intercession of the US authorities in restructuring the banks, savers would have faced many bank failures with a knock-on effect on the other side of the Atlantic. The QE policies undertaken by the FED have helped protect the operating principles of credit and trade in Western societies.

US Nominal GDP indicator in dollars

US Nominal GDP indicator in dollarsNominal euro area GDP in euro

Nominal UK GDP in SterlingSource : Chart 2

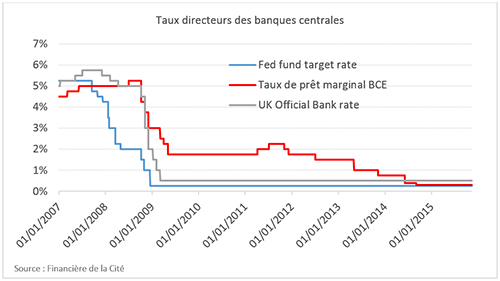

In contrast the euro area whose government and private debt levels were lower than those in the Anglo-Saxon economies were more severely affected (Chart 2). They have not recovered their pre-crisis levels unlike the Anglo-Saxon economies. Debt and unemployment have risen, internal imbalances within the euro area have increased. The claim made about "structural impediments" linked in particular to the cost of labour and the level of government spending, is not enough to explain this difference, as the vigour of the European economic recovery in 2009 illustrates. Explanation can be found in the upkeep of a restrictive monetary policy in a context of budgetary contraction, since the ECB committed rather late to quantitative easing operations and rather curiously proceeded to raise interest rates (in 2009 and twice in 2011) before returning to a "zero rate" policy in the following months (chart 3).

ECB Marginal Lending RateSource : Chart 3

ECB Marginal Lending RateSource : Chart 3

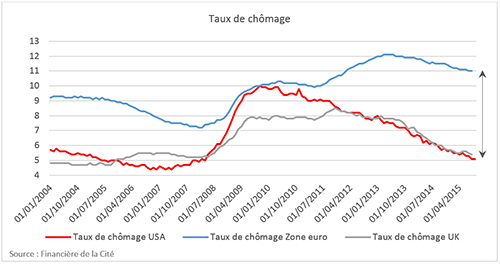

The combination of a restrictive monetary policy and budgetary contraction policies have damaged the countries of the euro zone. (Chart 4).

Unemployment rate USA

Unemployment rate USAUnemployment rate euro area

Unemployment rate UKSource : Chart 4

Since some economists who sometimes hastily claim they belong to the Austrian school support that it is the ECB's "honour" to have preserved the value of the currency and European purchasing power. This remains a question of debate. Until 2014 the ECB followed the same policy as the BoE in 1922, which, for political reasons decided to return to the pre-war parity gold standard, whilst the world conflict had overturned balances completely. We note that in similar circumstances (but under a long-standing integrated monetary zone!), some years later Moreau, then Governor of the Banque de France stabilised the value of the French franc at a fifth of its pre-war value leading to an influx in capital and the rapid restoration of financial balance [11].

The combination of restrictive monetary policy and demand contraction policies therefore have had highly negative effects on the euro area. In circumstances of exceptional crisis it is the central bank's responsibility to palliate the contraction in global demand to prevent the collapse of the economy. It is a well-established fact, notably in the wake of the work done by Friedman on the 1929 crisis [12].

In order to take these ideas forward, political will that was lacking on the part of the French elites, was required (which could only oppose German interests) [13]. The financial crisis might have provided a unique chance to create an integrated monetary zone and to take a European growth model forward in the face of the Anglo-Saxon and Chinese economies. Instead it highlighted internal balances between States, which had been hidden during the period of convergence.

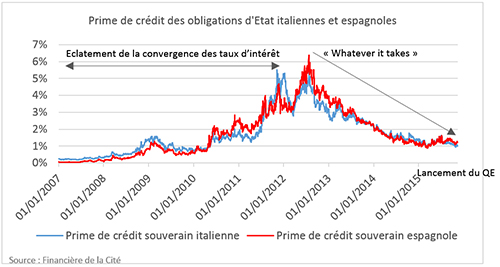

In effect the situation of the euro area's peripheral securities markets was not so different from that of the famous baskets of securitized subprime-backed assets, ranked AAA by the major ratings agencies. The euro masked the imbalances in current accounts between Member States, facilitated the expansion of capital from the European center (German, Belgian, Dutch and French banks) towards the periphery (Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Greek markets), by creating the illusion of an integrated market. Unlike the Fed, the ECB did not act to calm the markets when the crisis started (August 2010). Its interventions were limited to cash advances to the banking sector via long term financing operations. Tension on the euro area's interest rate markets only calmed in July 2012, following declarations made by Mario Draghi [14] (cf. chart 5), i.e. four years after the start of the crisis.

The ECB's inability to act as a central bank, i.e. as a reserve bank, therefore heightened tension on the interest rate markets, which in turn created an additional level of rigidity [15]. In this regard it led to the idea that intervention caps set by the monetary authorities played a negative role in encouraging the markets to test the limits that had been set [16]. In this context the implementation, contrary to all common sense, of cumbersome regulatory projects (Basel III, Solvency II), underpinned by a kind of bureaucratic inertia [17] increased pressure on the economy.

Credit premium of Italian and Spanish government bonds

Credit premium of Italian and Spanish government bondsCollapse of the interest rate convergence

Launch of QESource : Chart 5

The implementation of QE by the ECB at the end of 2014 did not appease uncertainty. Sovereign risks have persisted, and according to the rationale of "Banking Union" [18], banking risks are still addressed on national level according to the "bail-in" mechanism which means engaging the contribution of bondholders and depositors, before the implementation of any European financial guarantee [19]. Within the euro area the crisis went together with the renationalisation of assets [20]. The sovereign debt markets are therefore much less integrated and much less liquid than they were. The 19 euro area members are not safe from further financial difficulties, all the more so since the ECB's policy is increasingly contested, in Germany, where it is (wrongly) considered as a "minting plate" (since the leaders of the Bundesbank do nothing to invalidate this vision of matters), as well as in the countries qualified as "peripheral", which have suffered total contraction in credit.

Political uncertainty about the governance of Europe has added to these financial difficulties [21]. Ill adapted to a situation of crisis, the institutions of Europe have made inter-State relations more complex and more artificial, which is impeding the traditional state of diplomatic play. The ECB's QE does not enjoy the same level of legitimacy as that of the Fed or the BoE; in the absence of coordination in economic policy (even without going as far as a common treasury), it has gone together with many asymmetrical shocks [22].

B. Greater risk of financial and political instability

The more long term effects of QE on the financial markets and the economy are still of concern however. QE is having a pernicious effect on price formation on the financial markets, it compromises healthy economic recovery and goes together with high political and social tension. Again more in the long term, when linked with greater monitoring of financial activities (Basel III and Solvency II), there is a danger of the administrative control of the economy.

A discretionary credit allocation mechanism

Contrary to popular thought QE cannot be likened to a traditional "minting plate" policy. The money created by the central banks is not for the people. It is channelled by the central bank to the benefit of financial institutions (pension and investment funds etc.) and a small number of reputable banks which are "too big to fail". QE policies have therefore led the central bank to undertake the role of planner, by substituting, in a discretionary manner, the interplay of market forces. By maintaining low interest rates, whilst committing to support long term asset prices if necessary, by encouraging market operators, the central bank has left its traditional role of being a reserve bank behind.

Formation of financial bubbles

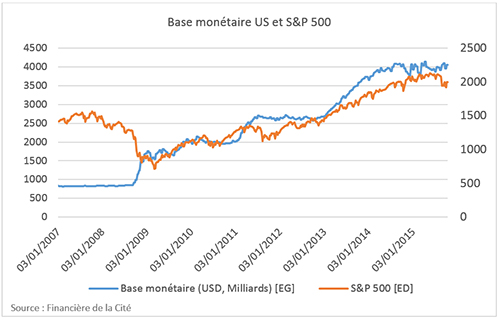

Asset purchase policies and forward guidance (comprising in central banks committing to the future trajectory of the key rate) have strengthened the self-referential nature of the financial system. As in 2003, when the Chair of the Fed committed to maintaining low interest rates "for a considerable length of time", thereby contributing to the formation of the American real estate bubble, market operators were directly encouraged to borrow short-term at low rates to invest in long-term assets (stocks and bonds), whilst benefiting from the implicit guarantee of the central bank [23]. Big businesses took advantage of this situation to purchase their stocks, whilst the financial institutions and investment funds engaged in massive processing operations. The expansion of the Fed's balance sheet went together with a constant rise in the stock markets (chart 6). The pursuit of yields led to critical accumulation points across an entire range of assets (government bonds, private bonds, convertibles, emerging debt, real estate) which led to a downturn in the quality of the portfolio, to the benefit of unsafe, illiquid assets (loans, securitisation operations and high yield securities).

In an open world, in which the development of major asset management businesses have increased the sensitivity of capital to bad news (or to the emergence of new investment themes), reactive forces can behave quite brutally, as shown by the sharp rise in interest rates at the end of April 2015. As the central bank has become a main counterparty, QE has deteriorated the liquidity of the bond markets. QE policies (like the famous "Greenspan put" in its time) are therefore long-term generators of financial instability.

Source : Chart 6

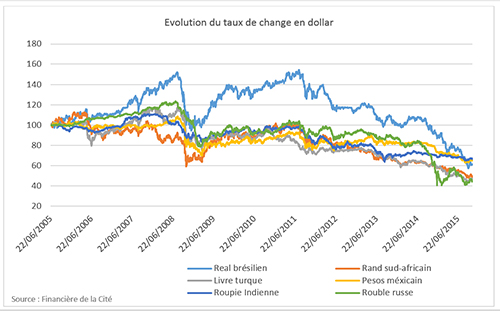

Source : Chart 6Increased Instability of the Emerging Countries

Undertaken by the central banks in the main developed countries, QE policies have fostered financing conditions of businesses in emerging countries by creating a real investment boom, often funded by debt. Criticism was notably made by Raghuram Rajan, Governor of the Central Bank of India, already author of a book on the imbalances of the American economy [24]. From 2009 to 2015, QE indeed led to an expansion of capital towards the emerging and developing countries, offering more favourable prospects of yield and growth as expressed by the BRICS. In spite of various measures to control exchange rates, businesses in the emerging countries incurred massive debts in dollars, notably via intermediary off-shore markets (Hong Kong for China). As the Geneva Report [25] notes, QE policies have gone hand in hand with rising overdrafts in dollars outside of the US and increasing debt in the emerging countries. Faced with a fall in raw material prices and the rapid depreciation of their currencies (Chart 7) emerging countries are therefore no longer able to take any further financial shocks.

Brazilian Real

Brazilian RealTurkish Pound

Indian Rupee

South African Rand

Mexican Pesos

Russian RoubleSource : Chart 7

Economic Stagnation

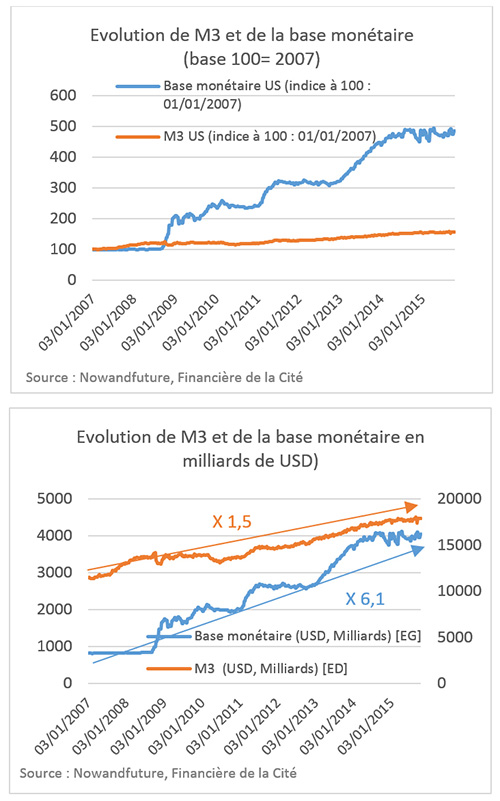

A more fundamental monetarist criticism has been made by monetarist economists [26]. Ultimately QE is the creation of "central bank" money in the shape of savings which are added to the monetary base (coins and notes + bank reserves). But as Henri Lepage quite rightly points out most money is created by the banking sector via the granting of new loans (loans make deposits) and via the refinancing mechanism (repo) of negotiable financial assets given as collateral [27]. On the eve of the financial crisis the share of the central bank's money in the entire American monetary mass was only 6.5%; since a major share of loans to the economy were provided in exchange for collateral assets delivered in the shape of guarantees. The increase in the monetary base remains therefore modest in comparison with the overall volume of credit flows into the economy and has relatively little effect. Hence in spite of unprecedented intercession by the Fed, the overall volume of the American monetary mass, in the widest sense of the term (M3) has stagnated and its growth rate remains below the total achieved prior to the crisis (chart 8). A similar situation can be seen in Europe. Henri Lepage notes that "against all expectations, the adjustment of money creation has remained extremely restrictive during this entire period." [28] The ratio between the total amount of credit flows to the economy (M3) [29] and the monetary base has indeed contracted during the entire period of expansion of the central bank's balance sheet.

Development of M3 and the monetary base (in billions of USD)

Source : Chart 8

Source : Chart 8

The accelerated implementation of the Basel III reforms and zero rate policies has increased the restrictive trend monetary policy. Banks have been encouraged to reduce their leverage by reducing their overdrafts or by increasing their capital. Deprived of a positive scale of interest rates (due to the overwriting of term premiums) they have deemed it preferable to retain their resources in their reserve accounts at the central bank rather than lend with a zero margin to fragile businesses in a period of crisis. QE policies and low rates have therefore led paradoxically to a rationing of loans, to the detriment of SMEs which have not had access to commercial paper. The recessive effect of these policies is particularly visible in France and in the countries of Southern Europe or in businesses that mainly depend on bank credit.

Intergenerational transfer of financial imbalances towards the youngest

From a general point of view QE comprises spreading the cost of the crisis between the debtors and the creditors via the taxation of private savings. However not all creditors can be viewed in the same way. Most adjustment is borne by young workers, who are forced to save at long term historically low interest rates, whilst bearing the burden of the retirement of the post-war generations. Investors, who held large portfolios of investments in government bonds have however raked in substantial profits. By reducing interest rates without managing to revive inflation QE policies have led to an intergenerational transfer of the crisis over to the younger generations.

Political and social tension

Finally QE policies are contributing to the development of high social tension. In the USA as in the euro area there has not be a "trickle" of liquidities towards the real economy. Low interest rates and policies to purchase assets have benefited the holders of financial assets and real estate and financial operators. However populations have been severely hit by the crisis and businesses, which did have not had access to the markets, have suffered credit contraction. Hence the idea has spread amongst the public that "austerity" is for the "Have Nots" and that the "Haves" have profited from a scandalous speculation premium. In the USA and in the Anglo-Saxon economies asset purchase policies have gone together with increasing inequality [30]. Polarisation in political debate with the unprecedented rise to power of people working on the edge of traditional government parties (D. Trump, B. Sanders) is the symptom of this tension and a kind of deterioration of American democracy as described by Tocqueville.

Since the capital markets are interconnected the destabilising effects of American QE were also felt in the euro area, although the ECB maintained a restrictive monetary policy throughout this period. Differences grew between major companies who were trading with countries outside of the euro area and which had access to the capitals markets and SMEs, which were hard hit by the contraction in demand and credit. The upkeep of internal demand contraction policies increased internal imbalances in the euro area: geographic and sectoral polarisation, marginalisation and desocialization of the youngest. As Allais said, in zones of fixed exchange rates adaptation via internal prices is long, uncertain and costly both on the political and social levels [31].

The endurance of the populations, the resistance of the territories, solidarity between families and the political maturity of the electorate have enabled the absorption of the effects of these internal demand contraction policies until now. However opposition has grown between Germany and the other countries of Europe, whilst QE implies a common agreement to overcome the burden of the debt. Since transfer policies, both financial and sovereign, are increasingly misunderstood and rejected by the populations, the outcome of the situation seems extremely uncertain.

Technocratic economic management

QE is part of a technocratic rationale in the mechanisation of financial activities [32], which also underpins financial regulation (Basel III, Solvency II). From this standpoint banks and financial intermediaries are responsible for allocating credit to the economy according to "incentives" calibrated by government authorities, who themselves are informed by panels of experts. The rise of technocracy in the guise of "governance" answers a social demand conveyed by the administrative elites and the media. However, there is a danger of disempowerment of those players, together with a kind of economic and political decline. Moreover the standardisation of behaviour increases systemic risks.

Loss of innovation capital

Finally, in combination with a tightening of prudential rules QE policies are leading to a loss of innovation capital and a poor allocation of resources: banks are momentarily called to increase their own funds to the detriment of any increase in risk-taking, major industrial groups prefer to purchase their own shares rather than take forward new projects, insurance companies stock up with State bonds. Capital becomes scarcer, SMEs are forced to seek other finance sources (loan funds, private equity) which leads to short-term expectations and creates further liquidity constraints.

III. Returning to traditional monetary policies

A. Natural normalisation is difficult

A smooth transition out of QE policies seems difficult. Every attempt to restore a more normal monetary policy ("tapering", increase in key rates etc.) comes up against investor expectations which then affects action taken by the central bank. Possible increases in interest rates are limited by the risks of debt-deflation, but conversely abnormally low rates constrict credit by creating accumulation points on financial assets and real estate, without contribute towards economic recovery. Central banks, and in particular the Fed, are trapped by the expectations that they have created.

Indeed we might ask the central bank not only to be a reserve bank, ensuring the centralisation of monetary resources, but also to act as a price regulator via the expansion of its balance sheet. Of course, as we recalled in the first part of this paper, it is the traditional purpose of a central bank to "provide trade with money" when confidence evaporates. The novelty of QE policies lies in using the central bank's credit to maintain a certain interest rate and price levels indefinitely without ever undertaking the direct emission of paper money. Hence QE creates a kind of "repressed inflation": collateral prices increase, lending to the economy contracts, whilst the surplus liquidities thereby created pour into the financial markets. Distortions in asset valuation undermine confidence and skew the references that are vital for the smooth functioning of the economy. How can this vicious circle be brought to an end?

The answer to this is complicated in that monetary policy is influenced by normal economic development and by State intervention during periods of crisis. In our opinion it depends to a great extent on developed countries' ability to absorb the slowing of emerging economies, particularly China.

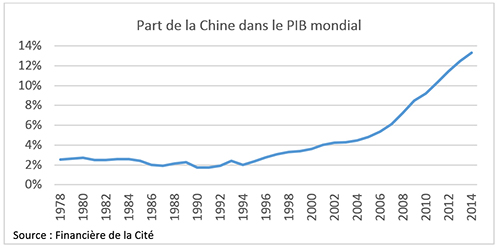

Chinese growth is indeed "the elephant in the room"; the deep-rooted cause of the economic crisis - far more than financial innovation and the level of government debt [33]. In less than 20 years China's share in the world's GDP has tripled (Chart 9). The entry of millions of men onto the labour market has had a massive deflationary effect on the economy. Low labour costs and the abundance of Chinese savings, which have mainly been re-invested in Chinese bonds, reduced interest rates across the world by creating massive over investment in the real estate markets typified by a traditionally low level of private saving and the extensive use of lending mechanisms (USA, UK, Ireland, Spain). The market has naturally responded to this state of affairs by providing operators with securitization tools that have enabled some to incur debt and others to benefit from a yield outperformance in an environment of low interest rates [34]. This is the structure that collapsed in 2007-2008 and made intercession by the central banks necessary.

Source : Chart 9

Source : Chart 9

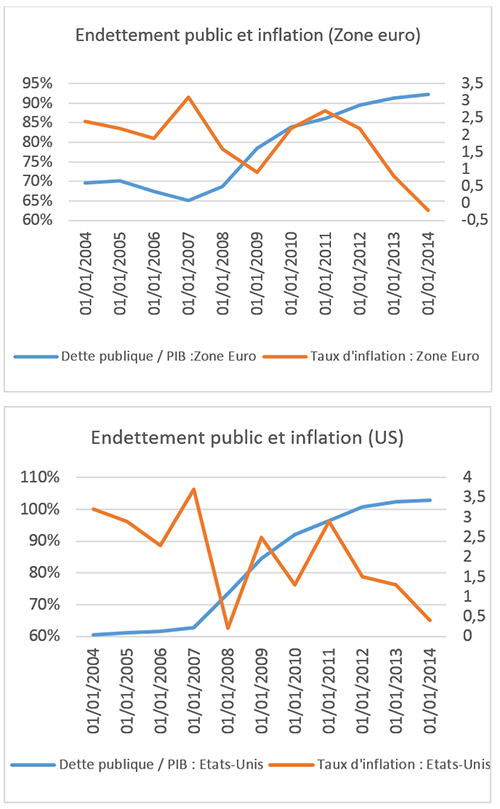

So far QE policies have been powerless in counterbalancing the profound and permanent effects of China's impact on world prices. Hence there is low growth, central banks are fighting to counter deflation and increasing debt (Chart 10). With no international, independent standard, with destabilising flows in capital, another currency war, a nationalisation of some economies cannot be ruled out.

To date the particular status of the dollar, as well coordination on the part of the major central banks, have prevented these problems. The USA has decided to adjust the rise in interest rates to the slowing of emerging economies [35]. The ECB and the BoJ have taken over from the FED in terms of QE policy. China is preparing for the internationalisation of the renminbi. However in view of the most recent inflation and growth figures, there is nothing to indicate that the present policies will be enough to counter the trend in declining world prices. The natural end to QE policies via growth, the progressive re-establishment of budgetary balance etc. seems to be highly compromised, notably in Europe where security issues have once again come to the fore. Unless we come up with other means of monetary action the developed economies will therefore have to find agreement in terms of sharing the burden of the debt and of spreading the cost between debtors and creditors.

Government Debt and Inflation (US)

Government debt/GDP:US Inflation rate: US

Government debt/GDP:US Inflation rate: USGovernment debt/Euro area GDP Inflation rate: euro area

B. Restructuring government debt

Whatever these operations might have achieved, QE never creates permanent purchasing power. Advances to the central bank always have to be reimbursed. A central bank only creates purchasing power by increasing the mass of monetary means available to the public. If growth is not recovered, the only way out in terms of recovering controllable levels of debt and "normal" monetary policies might be to inject newly created money directly into the economic circuits. As he referred to Friedman, Ben Bernanke recalls that "sufficient injections of money will always overcome deflation. Under a regime of paper money the government can always increase nominal revenue and inflation even though short-term rates lie at zero."

Ultimately, as Milton Friedman, the guardian of monetary orthodoxy illustrated, like many before him [36], fluctuations in the monetary mass in the widest sense of the term facilitate economic growth. The quantity of money is not the cause of growth but it helps. The development and world expansion of the European continent during the Renaissance can mainly be explained by the inflow of gold which had a decisive effect on prices and the speed with which money circulated [37]. Conversely restrictive policies undertaken by monetary authorities (as the Fed did in 1930) make crises more acute as they wrongly contract money supplies.

The emission of paper money (just like the increase in the production of gold under the gold standard) is therefore the absolute weapon with which to counter price decreases. Moreover by increasing the nominal GDP the emission of money erodes the real burden of the debt. This is the solution with which the USA and the major developed countries brought high debt levels to an end after the last world war. This type of policy was also successfully undertaken in the 1930's by the Prime Minister of Japan Takahashi Korekiyo, who is often quoted as a reference point by Ben Bernanke.

The central banks hold a growing share of government debt and can easily recapitalise by creating money. Since they are the origin of the world's money supply they have a wealth of techniques at their disposal to inject money directly into the economy without frightening the proponents of monetary orthodoxy: they can decide to monetise their considerable stock of bonds which they have acquired, proceed directly or indirectly to the financing of government deficits, take part in major investment projects etc. At the same time, a vast compensation operation between central banks and National Treasuries, undertaken under the aegis of the BIS would also be possible [38]. It would enable every major country to recover a certain amount of leeway: debt levels in the major countries would return to pre-crisis levels, the restructuring of debts would go hand in hand with a return of inflation, the normalisation of monetary policies and an end of "zero rates".

Unless there is a "deus ex machina" (a new major technological revolution for example), the transition out of QE policies should in our opinion be reflected in the long term restructuring of government debts and the return of inflation. The upkeep of free trade and central bank coordination is however a vital condition for this. The downturn in the situation in certain major developed countries might indeed lead to a nationalisation of the financial markets, a kind of economic withdrawal and repressed inflation. The situation is especially worrying in Europe where the management of the crisis has accentuated the fault lines. The path towards an end to QE policies is therefore narrow and perilous.

Conclusion

However effective they might be, the means used to increase the base currency to save banks of bankruptcy are simply palliatives. As Allais noted, when a house is burning, the fire has to be put out first, whatever the cost. But this will serve little purpose if we have not remedied the causes of future fires. The failure of QE policies has highlighted the weakness of a badly established monetary system. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the rise of China, the opening of the markets and technological progress have led to a general instability in capital and greater competition between monetary zones. The problem to solve is not a new one. The return of a common standard on the basis of which trade might be established and which protects the public against governments' monetary and financial arbitrariness is highly desirable; this was the logic behind the European currency. This solution supposes however the respect of economic and financial discipline by all participating States. We have seen the problems that this raises. In these conditions the upkeep of open cooperation between central banks is vital to prevent any further disruption.

[1] : The book by C. Rist, Histoire des Doctrines relatives au Crédit et à la Monnaie (Sirey, 1938) is a reference work in terms of understanding the origin and role of central banks.

[2] : This idea was defined quite clearly by Warburg in his articles for the creation of real Reserve Banks in the USA. The Central Bank is the reserve where all banks can use to find supplies and to satisfy their clientele's liquidity requirements. It is both the "hammer" and the "anvil": it must both restrict itself to a passive role, waiting for discounts to come from the market according to its requirements, and take the initiative to intervene on the market to increase its liquid assets via the purchase of government bonds at relatively short maturity.

[3] : When gold established de facto solidarity between the various international markets it was the movements of precious metals that mainly defined the orientations of monetary policy and the variations in discount rates (the equivalent of the key rate of the central banks today). The central bank was advised to increase its discount rates during periods of economic expansion to defend its bullion, prevent surplus credit and compensate for downturns in foreign exchange rates.

[4] : The most recent ideas already mentioned by Keynes and certain economists prior to the 1914-1918 War, are being revived again today to foster an increase in the circulation of money. The libertarian blogosphere has often echoed these projects to denounce the attack on cash and the challenge made to individual freedom.

[5] : Quarterly Bulletin of the Bank of England, first quarter 2014, p. 24.

[6] : B. Bernanke, "The Crisis and the Policy Response", speech at the London School of Economics, 13th January 2009.

[7] : L. Bini Smaghi, "Conventional and Unconventional Monetary Policy", speech at the International Centre for Monetary and Banking Studies, Geneva, 28th April 2009.

[8] : Since the European Central Bank is not a real reserve bank (nor an emission institution, a task that is still the domain of the national central banks), but a sui generis administrative body responsible to setter a exchange rate agreement, its action is part of a more complex political framework: vis-à-vis the outside, it acts as would a modern national central bank, whilst it behaves as if it had to defend the bullion of its shareholders vis-à-vis Member States. This is one of the reasons why it committed rather later and with extreme reticence in QE policies and according to specific conditions.

[9] : Alongside this action in 2009 China launched a far reaching investment plan of nearly 600 billion dollars to finance infrastructures. This is also a kind of QE policy.

[10] : QE central bankers deserve a medal for saving society, Telegraph, 29th October 2014.

[11] : The memoirs of Governor Moreau were published in 1954 with a preface by Rueff. Having a purely technical view of their tasks, the executives we send to the ECB are totally unaware of the history of monetary policy, which for them is the focus of curiosity and amusement. However the acknowledgement of particular features of history, psychology etc... of each monetary market in the euro zone might have helped prevent many errors.

[12] : The Allais analyses move in the same direction. During the Asian crisis in 1998 he declared that given the "crisis, what we have to do today has been known since the Great Depression of 1929-1934. We must avoid any reduction in global spending and ensure that it increases" (Interviews with P. Fabra, Politique internationale, 2nd December 1988). The euro zone authorities have done exactly the opposite.

[13] : The unspoken, pusillanimous fear of Germany, alienation from economic realities, the disdain of the senior public administration for academic know-how, many factors explain the failure of the administrative and political elites which emerge in other domains.

[14] : Whereby the ECB supports the euro with, "whatever it takes". This cleared market uncertainty and led to a sharp decrease in the long term interest rates in the euro zone, without being followed by an effective intervention by the ECB. According to reality which is that of the financial markets, the statements are performance oriented: saying is doing. The ECB has lost a great deal of time.

[15] : The ECB's situation is clearly the reflection of the balance of power in continental Europe which has been totally disrupted since France handed over the management of the single currency to Germany. The long term consequences of this decision have not been assessed very well. A sovereignty tool was granted to a provincial State whose economy is mostly turned towards the exterior of the euro zone and which is not able to exercise "imperial" responsibility.

[16] : With this in mind, Bagehot criticised the Peel Act (1846) which whilst granting the monopoly of emission to the Bank of England, established limits that were too rigid from the point of view of steering the discount rate, thereby limiting its ability to act in the event of a financial crisis. Thiers noted the superiority of the rules governing the Banque de France on this point. The Banque de France was also to serve as the model for Warburg in the creation of the Fed.

[17] : The obstinacy in implementing these reforms (which added useless regulatory viscosity to key economic sectors and whose intellectual foundations were mostly swept away by the financial crisis) is extremely revealing in terms of a neo-conservative, authoritarian trend in European democracies. We note in this regard that the American banks and insurance companies did not set these constraints upon themselves.

[18] : It is strange to qualify a measure that sanctions the financial fragmentation of the euro zone as " Banking Union ". The new contemporary administrative language is full of these euphemisms.

[19] : The complexity of this mechanism makes its effective implementation very uncertain. Moreover the discretionary powers that the bank regulation authority has should require more serious guarantees. It is strange that Europe allows the development of an organisation within its midst that accumulates powers to regulate, investigate and to sanction without any counterbalance.

[20] : Hence in France, the main institutional investors withdrew completely from the debt markets in the countries of southern Europe. The ebb of capital also involved all of the North of Europe. Prudential regulations (Basel III, Solvency II, financial regulation, ARRCO-AGIRC in France) encouraged this movement by giving normative value to indications provided by the ratings agencies.

[21] : On this point see the article by T. Chopin and JF Jamet, Europe and the Crisis: What are the possible outcomes? European Issues n°219, Robert Schuman Foundation, November 2011.

[22] : Hence the drop by the euro against the dollar mainly benefits the economies that trade with countries outside of the euro zone and therefore Germany and its subcontractors (Poland, Slovakia etc....) in the main.

[23] : The so-called "forward guidance" policies comprising the central banks' commitment to the future trajectory of the key rate have strengthened the self-referential nature of the financial system.

[24] : Fault Lines, How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. 2010. The paper by R. Rajan on the effects of QE on the emerging economies is available on the International Settlements Bank site.

[25] : Deleveraging, What Deleveraging? 29th September 2014

[26] : S. Hanke, former member of President Reagan Economic Committee; W. Williamson, economist at the FED Saint Louis. Henri Lepage is the chief representative of this trend of thought in France, this paragraph takes up his analysis.

[27] : These operations grew sharply as of the 2000s with ITs, the accumulation of significant trade surpluses by China, low interest rates and the rarefaction of the supply in American treasury bonds in the wake of government deficit reduction policies undertaken by the Clinton administration.

[28] : H. Lepage, Sortie de crise : quel scénario ? Politique Internationale, n°139, Spring 2013,

[29] : The M3 figures are no longer provided by the American authorities. Some specialised web sites (Nowandfuture, Shadowstats) recalculate this data.

[30] : The rise in the death rate of "middle-aged white Americans" reflects this disenchantment with the American dream Cf. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century Anne Case and Angus Deaton, PNAS, September 2015.

[31] : "The natural regulatory parameter of the balance of the balance of payments is mainly the exchange rate. Wanting to achieve balance in the balance of payments via action on price levels or on the interest rate can only lead to greater difficulties than the ones we want to remedy." M. Allais, Caractéristiques comparées des systèmes de l'étalon-or, des changes à parités libres et de l'étalon de change-or, in Les Fondements philosophiques des systèmes économiques, Mélanges de textes en l'honneur de J. Rueff, Payot Paris, 1967.

[32] : In this sense in various articles H. Rodarie, Delegate CEO of the SMABTP presented the "cybernetic" model on which financial regulation is based, which led, in his opinion to a risk of "resonance" of financial operators.

[33] : The destabilising effects of China's incursion in the world economy are comparable to those of the development by the USA at the end of the 19th century, which led to the implementation of protectionist policies across Europe and a withdrawal of national economies. On this point cf the good book by Mr. Prasad, The Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty, Harvard University Press, 2012.

[34] : "Finance" is therefore not responsible for the financial crisis. Collusion between ratings agencies and banks, the implicit guarantee given by the FED to market operators, the situation of political irresponsibility in which many executives of institutions are placed as they take cover behind "benchmarks and the opinions of consultants have all contributed to creating the bubble.

[35] : We too often forget that the dollar is also a burden as well as an "exhorbitant privilege" for the USA. The FED cannot ignore the impact that the end of its monetary stimulation policies would have on other parts of the world. In this sense the dollar is really the only world reserve currency.

[36] : Bodin, Law, Cantillon, etc.

[37] : The British industrial revolution was financed with gold from Brazil, which mainly went to English trade due to its privileged links with Portugal. The discovery of mines in the Transvaal at the end of the 19th century led to comparable effects after many years of European economic stagnation.

[38] : This idea was drawn up by X. Strauss, economist, during a conversation with the author.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

Strategy, Security and Defence

Jean Mafart

—

27 January 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :