Institutions

Ramona Bloj,

Cindy Schweitzer

-

Available versions :

EN

Ramona Bloj

Cindy Schweitzer

In this context, note the reorganisation of the Commissioners' College. This involved notably the appointment of a first vice-President, Frans Timmermans, presented by Jean-Claude Juncker in 2014 as his "right hand man". In addition to the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, the Commission comprises 6 vice-presidents, which has resulted in a distribution of commissioners by project teams and "supervision" by vice-presidents who, in many cases, have been Prime Ministers in their own countries (Jyrki Katainen, Valdis Dombrovskis, Andrus Ansip), as recommended by the Robert Schuman Foundation prior to the 2014 elections. As from 1st November 2014 communications were also directly attached to the Commission President.

Politically, the Commission is responsible to the European Parliament, which approves the College of Commissioners (article 17, paragraph 7, TFEU) and hears them (article 230 of the TFEU). Also, according to the treaties, Parliament has to power to issue a vote of defiance against the Commission (article 17 TEU and article 234 TFEU). Although the Spitzenkandidat procedure reinforced links between the two institutions, the Juncker Commission had to find a way of being more "political" in its relations with the European Council, and distance itself from the trend which sought to qualify it as the "second general secretariat".

Because, although officially the European Council gives the Union impulses and general political directions, and establishes its priorities whilst being legally excluded from any kind of legislative function (article 15, paragraph 1, TEU), it has seen its influence increase following the management of the multiple crises with which Member States have been confronted.

The treaties state that the Commission can make proposals on its own initiative separately from the European Council. It has gradually broken free from the strict framework of its jurisdiction under cover of the principles of subsidiarity, whilst however respecting the principle of proportionality. Thus, even though the number of legislative acts fell under the latest mandate, we have witnessed a production that takes a variety of forms: communications, objectives, decisions and citizen consultations. It should be remembered that the Commission is both the executive body of the Union and also a real administration, itself supported by 75% of European civil servant staff. This capacity, which should be put into perspective compared to numbers of national civil servants[1], gives it however a "strike force" which, although it cannot propose to legislate on all public policies, enables it to intervene to varying degrees on several topics, particularly since it is not responsible for implementation in the field of European decisions, which remains under the jurisdiction of national administrations.

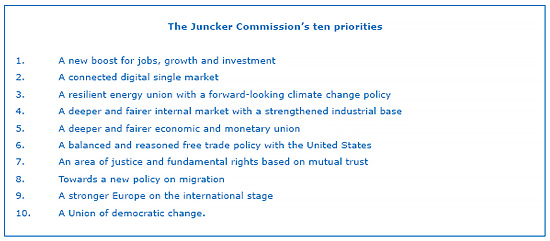

Although under the current mandate, the Commission was able to adapt and react to the banking and financial crisis that affected Member States, the Juncker era underwent other forms of crises and international mutations. The Commission had to show proof of resilience whilst keeping focussed on the measures defined in response to the 10 priorities set by its president at the start of his mandate. Jean-Claude Juncker could not ignore the economic situation when he took up the job. In 2014 unemployment still affected 10.4% of European citizens and more particularly 21.7% of young people. As for investments, their level was still well down compared to the pre-crisis position (-10% in 2008). Finally, public debt still represented 88.3% of total GDP in the Union.

The legacy of President Juncker's mandate remains positive: throughout the numerous crises and geopolitical changes that have taken place since 2014, Europe has continued to make progress and to adopt difficult texts on important subjects. One observes that, over the years, the Commission's proposals have gained in ingenuity with regard to definition of the legal basis: remember the proposals concerning migrant quotas, the creation of a European "Minister" for the economy and finances, or the skill with which it dealt with defence matters, extending to the limits of its powers.

I - The European Commission faced with successive crises and international change

A- Intrinsic crises

The democratic crisis

The respectable level of participation recorded during the last European elections (50.95%) should not lead one to forget the lack of mobilisation observed five years' previously (42.6% in 2014). Added to this are the higher scores achieved by Eurosceptic parties in both the 2014 and the 2019 elections.

Within this context, the Commission has continually reinforced the involvement of citizens in its decision-making process[2]. The reform of the European citizen's initiative has made this democratic tool more accessible, with a collaborative platform on line and a free signature-collection service. Since November 2014, 22 initiatives have been recorded (1 retained, 7 in hand, 10 rejected and 4 withdrawn).

Nevertheless, the mechanism remains controversial in view of procedural difficulties. There are other tools for European citizens such as Futurium, the web forum for discussions about European policies (the latest request concerns artificial intelligence) or the Refit programme platform, to improve the formalities linked to a legislative act. Finally, numerous public consultations are regularly opened on line.

Follow-up to the Greek crisis - a matter for States

The stigmata of the financial and banking crisis have been gradually erased since 2008. Even though Greece has seen a primary budgetary surplus since 2013[3]. In January 2015, a few months' prior to the term of the second rescue plan, decided in 2012, the Greek people elected the radical left-wing party, Syriza, into government. Extremely tense negotiations then followed between the Greek government and the Troika, to which the Commission belongs, together with the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. At the peak of this crisis, during the referendum in July 2015 on whether or not to accept the proposed plan, the risk of Greece leaving the euro zone was at its greatest. Jean-Claude Juncker, who was against this alternative, got to work with the support of a few Member States, willing, if necessary, to go beyond his role. Since the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was the competent body in this respect, intervention by the Commission for the release of funds to support Greece was indeed limited. It was not until 2018 that a protocol of agreement was signed setting out the working relationship between the two institutions. The Commission did intervene nevertheless in terms of optimisation of funds for Greece, mobilising €35 billion over the period 2015-2020 and offering administrative technical support via its support for structural reform department.

The quarrel over the name of Macedonia

Another disagreement with Greece, which received much less media attention, concerned the name of Macedonia. In the Prespa agreement of 12th June 2018, the Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsípras, and his Macedonian counterpart Zoran Zaev agreed that the country would be officially called "Republic of North Macedonia". On 12th February 2019, after ratification by both parties, the agreement came into force, thus unblocking North Macedonia's membership of NATO, and its application to join the European Union. This appeasement would probably not have come into being without the Commission's strategy towards the Western Balkans.

The migrant crisis: European proposals, national blockages

Contrary to the financial crisis, the migrant crisis reached its peak during the mandate. Originating to a large extent in the Syrian civil war, triggered during the 2011 Arab Spring, migrant flows to Europe culminated in 2015.

Germany, the UK and Sweden were the preferred final destinations of the refugees, but countries under direct migratory pressure were those that allowed the migrants access, that is Austria, Italy, Greece and Hungary.

In addition to highlighting the deficit in the Union's foreign policy, this situation also underlines the limits of the Schengen area, where each State is responsible for managing its own external European borders. The question raised then is that of the management of requests for asylum. In this context the Commission issued an initial proposal of agreement to relieve those countries required by the Dublin regulation to manage and retain applicants. Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, which are used to cooperating within the context of the Višegrad group, showed a united front in this case. They all refused to welcome asylum seekers to their countries within the context of a mandatory distribution system.

In fact, Hungary, as a transit country which suffered only relative temporary pressure, did not agree to meet all the new demands proposed by the Commission. However, these countries were not the only ones to refuse the Dublin III regulation, which makes the States of first entry responsible for dealing with asylum applications. Conversely, Germany was somewhat exemplary in this respect. After this initial aborted attempt, Jean-Claude Juncker, during his annual speech on the state of the Union in September 2015, reminded States of their past and their heritage in terms of solidarity and called on their responsibility. Finally, in view of the urgency and scale of the phenomenon, a temporary, non-obligatory[4] agreement was found, thanks to support from Schengen area Member States. If we must remember anything from this episode it is that, like Germany, the Commission gave an example of reactivity.

The answers were to be found in an agreement with Turkey (€4.2 billion paid in aid), and in its development policy, with 1.5 billion taken from the regional trust fund for projects benefitting 2 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, the Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq (together these countries welcomed up to 4 million refugees at the height of the crisis in 2015). The Emergency Trust Fund for Africa for its part finances projects aimed at remedying the causes of illegal migration with a budget of €4.2 billion, and the public and private external investment plan, of a total amount of €44 billion to be operated by 2020 is destined for Africa and the Union's neighbourhood countries (renewable energies, agriculture, digitalisation, microenterprises, etc.).

Mention may also be made of the existence of a fund for internal security, aspect "External borders and visas" representing a total of €2.76 billion over the period 2014-2020. This aims at guaranteeing a high level of security within the European Union without restricting freedom of movement. Achievement of this objective involves strict, uniform controls at the Union's external border in order to combat clandestine immigration, and efficient processing of "Schengen" visas, guaranteeing equality of treatment for nationals of third countries, with a respect for fundamental freedoms.

The problems of temporary re-establishment of controls at internal borders have not been resolved (cf. terrorism). Similarly, no common asylum regime has been negotiated, guaranteeing a joint legal framework covering the entire asylum procedure with the support of an existing dedicated agency, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO). As for the development of Frontex, now the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, it is still only taking baby steps, with just 1600 guards at the external borders of Bulgaria, Greece, Spain and Italy.

Issues around the Commission presidency

The Luxleaks tax scandal erupted only a few days after Jean-Claude Juncker took office. This involved historical advantages granted under the cover of tax rulings for major multinationals located in Luxembourg. These practices, although legal since they complied with national regulations, posed ethical questions and were thought to be the origin of distorted competition within the Union. The affair also took on a moral aspect since the whistle-blowers were subjected to legal proceedings.

A so-called fiscal transparency package was proposed and then validated in 2015. The automatic exchange of information regarding tax rulings granted were limited, however, to States between themselves, without no access to either the Commission or the general public. Then, several versions of lists were drawn up of tax havens outside the Union. It is important to remember that the Union's competency is limited in terms of taxation to the correct functioning of the internal market and to measures are taken only after a unanimous vote by Member States in the Council. Several enquiries into distortion of competition have been opened on multinationals located in Luxembourg and have resulted in the levying of fines (Amazon, Fiat), as well as in the Netherlands (Starbucks) and Ireland (Apple).

The other controversy concerned the way in which Martin Selmayr, director of Jean-Claude Juncker's cabinet, was appointed to the position of deputy general secretary to the Commission in March 2018. Since then the European mediator has considered the issue and has observed irregularities whilst the European Parliament has held several non-binding votes calling for his resignation.

The first time a Member State has announced its departure

In a referendum held in June 2016, the United Kingdom voted in favour of leaving the Union (Brexit). This was the start of a long process of unexpected developments; for David Cameron's government it had been a question of honouring a campaign promise and was an attempt to bring together disunited members of the Conservative party! For the United Kingdom, free trade and competition are of historic importance. Its defiance of European legislative power is common knowledge. The obligation of European solidarity, within the euro zone and in terms of immigration, probably tipped the balance for the British people, nevertheless the majority in Scotland and Ireland voted in favour of remaining in the Union. Since June 2016 there has been a succession of episodes in the process of the United Kingdom's difficult departure from the Union, and departure is now set for 31st October 2019, although there is still no certainty in that regard.

The question of the rule of law and European values

2014 was the year in which Viktor Orban was re-elected as Prime Minister of Hungary, under the banner of Fidesz. In 2015, Andrzej Duda, candidate for the Law and Justice party (PiS) became President of Poland, with the support of Jaroslaw Kaczynski. In Romania, the 2017 victory of the Social-Democratic party (PSD), under Liviu Dragnea, threatened to make the corrupt Romanian legal system even more fragile. At the end of 2017, the extreme right-wing Freedom Party (FPÖ) entered a coalition government in Austria. That same year saw in the German Bundestag the arrival of 92 members from the AfD party (Alternative für Deutschland) and qualification for the second round of the French presidential elections of Marine Le Pen (National Front, now renamed National Rally). In 2018 an atypical government was formed in Italy comprising the 5 Star Movement and the League.

In fact, the rule of law is under threat in both Poland and Hungary. The independence of the justice system is in danger in Romania, corruption is a curse in Bulgaria and note should also be taken of the assassination of journalists in Malta in 2017 and in Bulgaria and Slovakia in 2018.

The Union has very few tools at its disposal to defend the rule of law. There is of course recourse to article 7 TEU, which provides for sanctions going as far as the suspension of the right to vote for the State in question, but this has to be voted unanimously by the Council (with the exception of the State concerned). The planned multi-annual financial framework (2021-2027) presented in 2018 proposes to link the obtaining of European funds to respect for the rule of law. In fact, the European Parliament voted several resolutions against Hungary in 2017 and 2018, which have still not been passed by the Council. The Budapest government can rely on its allies in the Višegrad group, and particularly Poland, which was also the object of a triggering of article 7 by the Commission in December 2017.

Although it is clear that solutions still need to be found in view of the limited scope of existing tools, by the very nature of decision-taking within the Union, we should note that in 2018 the Commission did achieve its ends against the Polish government by referring Poland to the European Court of Justice with regard to the law reforming the justice system in that country. Since the findings of the Court's advocate general were extremely favourable, the Polish government withdrew its law, without even waiting for the final decision. It would appear that the Commission intends to take similar action, with the support of the ECJ, in other cases of flagrant violation of the general principles of law. It has found the most efficient procedure by which to guarantee respect for the treaties.

B - Geopolitical mutations

Challenge to multilateralism: the election of Donald Trump

The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States at the end of 2016 is without question one of the most notable changes. To achieve his objective of "make America great again", his principle line of conduct, "America first" came down to destabilising as much as possible the multilateralism that has prevailed since the end of the Second World War. At the G7 meeting in June 2018, he saw the WTO (World Trade Organisation) and the European Union as his two enemies. He has threatened to leave NATO on several occasions. In Donald Trump's eyes, the Union is "a system that is much too complicated", which he refers to as "German Europe". He has also declared that Brexit is "great". His aim is to manage to divide Europeans within their institutions and to encourage populist and Eurosceptic parties. After increasing customs duties on the steel and aluminium exported by the Union, and having threatened to do the same on European cars, common ground was found in July 2018 after a trip to the United States by Jean-Claude Juncker and negotiations that he undertook personally with the American president. These resulted in a joint declaration on 25th July 2018[5].

Alongside all this, the Union rejected a demand from the United States to isolate Iran economically and updated a 1996 regulation known as the blocking statute, concerning European companies present in Iran, in order to counter American sanctions caused by their withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (Iranian nuclear deal).

During the summer of 2018, the Commission had to face the threat of the United States leaving the WTO. Considering that the latter spends more time on the settlement of disputes than on negotiations, Donald Trump continues to block the appointment of judges to the organisation's appellate body. To counter these difficulties, it is now proposing reform of the WTO and a plan to combat the subsidies that distort the markets[6]. Chinese practices are targeted in particular, whilst the Unites States contents itself with taxing Chinese imports.

More generally, European proposals consist of up-dating the rules governing international trade, strengthening the WTO's surveillance role and overcoming the blockage of its dispute settlement mechanism.

China's increase in power

The Commission has put forward several proposals in view of China's rapid rise on the international stage, illustrated by its demographic weight. In 2016 it was able to reach a solution to the dilemma facing the Union in terms of the question of knowing whether China's membership of the WTO made its passage to the (privileged) status of "market economy" automatic after 15 years. Contrary to the United States, which refused to grant China this status, the Union considered rather a change of method, by directly applying anti-dumping and anti-subsidy measures that put an end to the difference between countries that have a market economy status and those that do not.

Also, based on a proposal by the Commission, in April 2019 a new framework came into force concerning the filtering of foreign investment at European level, for better supervision of the Union's strategic interests.

In March 2019, the Commission also published a joint communication with the European External Action Service, in which China is no longer considered as "a developing economy", but as a "systemic rival" and a "strategic competitor". Whereas China is the top investor in renewable energies, the Commission denounced the building of coal-fired power stations in many countries, weakening the combat against climate change. China is also a protectionist country, which restricts access to its market by European companies "by the selective opening up of markets, the granting of licences and other restrictions to investment, as well as major subsidies to public and private companies".

Within this context, the Commission has requested the signing, by the end of 2020, of a bilateral agreement on investment and the "rapid signing of an agreement on geographical indications" and "air safety". It has also invited China to address the question of industrial subsidies, to meet its commitments under the WTO reform and to cap its CO2 emissions by 2030".

The Commission refused to allow the Union to be associated as such with the "Silk Routes" initiative designed by China to promote its interests.

The combat against terrorism

The Union is no longer spared from the rise in violence. Several terrorist attacks took place on European soil between 2015 and 2017, in France, Copenhagen, Brussels, Germany, the United Kingdom and Spain. These tragic events increased the determination of the 28 Member States to work together.

Member States can use the Internal Security Fund - ISF "Police" (police cooperation, crime prevention and repression, crisis management) i.e. a total of €1 billion over the period 2014-2020, which reinforces their ability to deal with risks linked to questions of security, to prevent and combat organised crime and halt the advance of terrorism.

As it did with tax havens, the Commission has drawn up a list of 23 countries identified as financing terrorism, after an initial list of 16 countries in 2018. The Council rejected it arguing a lack of transparency when it was drawn up.

A European Counter Terrorism Centre (ECTC) was created in January 2016, attached to Europol, an agency in which the Commission has only an observer's role.

Finally, in December 2018, stricter rules on money laundering came into force. Sanctions are now identical throughout the Union and result in at least 4 years' imprisonment.

Moreover, the Commission's legislative proposals are still being negotiated:

- Quick and easy obtaining of the digital traces of criminals, particularly terrorists, which can be used as proof for police and legal authorities.

- Automatic removal within a maximum of one hour of any on-line content of a terrorist nature.

Finally, other measures are in hand such as extension of the jurisdiction of the future European chief prosecutor to include cross-border terrorist offences or securing of the Schengen area. The issues of the temporary re-establishment of controls at internal borders within the Schengen area have not been resolved despite ideas put forward by the Commission in March 2016 (Return to the Schengen spirit) and in September 2017 (Preserve and strengthen Schengen). It is a question of finding a balance between management of threats to internal security and internal controls that must not hinder freedom of movement in Europe.

Note also the creation of the ETIAS, the European model of ESTA, which implies systematic checks on entering the Schengen area. It should be in place by 2021.

Environmental emergency

In December 2015, the COP 21 brought the international community together with, as its conclusion, signature of the Paris Climate Agreement by 195 States. Its aim in particular is to contain the increase in the planet's average temperature to below 2°C, or even 1.5°C. It also aims to reinforce the ability of signatory countries to adapt to the damaging effects of climate change, and make financial flows compatible with sustainable development. The European Union ratified the Paris Agreement on 4th October 2016. The Agreement came into force a month later, confirming progress in international action on climate. In this respect, the Union has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 80 to 95% by 2050[7].

In November 2018, the Commission presented its long-term strategy, calling for carbon neutrality in the Union by 2050.

In addition, a global strategy on plastics was adopted. After the measures taken in 2015 to overcome the problem of plastic bags, the Commission focussed on the ten single-use items and fishing materials which together represent 70% of marine waste in Europe.

Moreover, the future common agricultural policy[8] will be based on nine objectives that reflect its economic, socio-territorial and above all environmental multi-functionality.

II - Progress made by European public policies in view of the 10 priorities

Digital transition

For the Juncker Commission digital is a European priority with the proposal in May 2016 of a strategy for the single digital market. Objective: to bring together 28 fragmented national markets and attempt to face up to American domination. The proposal takes on a vast range of subjects from big data through to the regulation of internet platforms, on-line trade and the harmonisation of copyright.

The gradual reduction and then disappearance of roaming fees in 2017 is part of this strategy. More recently, the costs of calling abroad have dropped as far as being divided by 10. Digital is also an area supported by European funds (cf. Juncker Plan).

To enable Europe to remain competitive in terms of China and the United States in the field of artificial intelligence, at the end of 2018 the European Commission presented a plan of €20 billion private and public investment based on cooperation between Member States. This plan must meet 4 objectives:

- Stimulate growth in public and private investment,

- Encourage greater availability of the data that is essential for development,

- Cultivate talent by training European experts and retaining them, and by attracting specialists from abroad,

- Develop guarantees of confidence.

The Juncker investment plan coupled with the growth and stability pact

The investment plan for Europe was launched in 2014. The European Fund for Strategic Investment, which is part of it, had the aim of removing obstacles to investment, bringing technical assistance and mobilising private investment backed by an initial stake of €21 billion in public credit, which enabled double the amount to be borrowed on the bond markets.

This amount is broken down into a guarantee fund of €16 billion financed by the European Union budget and a contribution of €5 billion by the European Investment Bank (EIB). With a lever effect and mobilisation of private funds this mechanism enabled, according to the Commission, investment of €393 billion for 945 000 SMBs in various fields as well as for major projects such as infrastructure, research, renewable energies, the environment (7.2 million households have access to renewable energies), digital projects (15 million households equipped with broadband internet) and social projects.

The plan targets future-looking projects which could not have obtained finance from the EIB. It does not provide for either geographical or themed quotas. Member States are therefore not beneficiaries of the plan in any uniform way, although the European authorities do seek to deploy it across the whole of European territory. It completes but does not replace the traditional instruments of European cohesion policy, particularly structural and investment funds (ERDF, ECF, CF, EAFRD and EMFF).

The "six and two packs", which came into force in 2011 and then 2013, constitute a set of 7 regulations and one directive. The aim of the six-pack is to reform the stability and growth pact (SGP) and to increase the budgetary surveillance of Member States thanks to the European semester procedure, by giving the European Commission the possibility of demanding corrections to national budget plans and of inflicting sanctions. The two-pack completes it by reinforcing the transparency and coordination of national budgetary decisions, whilst taking better account of the specific requirements of the 19 States in the euro zone. The Commission went beyond this mechanism by offering a method that guarantees a good balance between these two directions: healthy budgetary practices that have led to reforms in certain States and support for growth via an investments policy (cf. Juncker plan).

The Union's economic performance has led the Commission to believe that this method of operation had a positive impact between 2014 and 2018:

- 6.8% reduction in public debt;

- Reduction in the deficit by 2.4% at 0.6%;

- Increase in GDP by 0.8%;

- Creation of 1.5 million jobs.

Reconfiguration of free trade agreements

The comprehensive economic and trade agreement (CETA) signed with Canada in 2016 came into force on 21st September 2017. This agreement removes over 99% of customs duties between the European Union and Canada, as well as restrictions in terms of access to public contracts. It harmonises the rules applicable in terms of intellectual property and provides for the institution of a court to settle disputes for the protection of investments. Only that part of the CETA that depends on the exclusive competence of the Union (i.e. 90% of the agreement) has come into force. Total application of the agreement will only be possible after its ratification - which is in hand - by the 43 national and regional parliaments of the 28 Member States.

An economic partnership agreement (EPA) has also been signed with Japan[9], it came into force on 1st February 2019 and applies provisionally whilst awaiting ratification by Member States. The trade zone created by this agreement includes over 630 million inhabitants and represents almost one third of world gross domestic product (GDP). It allows for the removal of customs duties on almost 90% of products exported to Japan by the Union (estimated by the Commission at €58 billion in goods and €28 billion in services annually).

Also, the Commission and Japan have mutually recognised each other's rules on the processing of personal data, and have created the world's greatest space for freedom of circulation of personal data (cf. GDRP). For the first time, within the context of a commercial agreement of this type, references to the Paris Agreement have been included. Negotiations on a strategic partnership were also undertaken at the same time. This consolidates the relationship between the European Union and Japan in terms of foreign policy and the promotion of values such as human rights, democracy, multilateralism and the rule of law.

We may also mention the signing of a free trade agreement with Singapore, which opens up access to a large section of ASEAN markets. Other agreements are currently being negotiated.

Measures with a view to forthcoming agreements

The negotiation of these agreements has, however, aroused much controversy, particularly the CETA. Much of this is linked, on the one hand to a supposed lack of transparency in the negotiations, noted by civil society in spite of numerous studies published on the economic, social and environmental impacts and public consultations undertaken. On the other hand, the parliaments of Member States consider that they were involved in the process too late.

The question then also arises as to the Union's jurisdiction in terms of the negotiation of trade agreements. Although it does have exclusive jurisdiction in this field, the new agreements include aspects that fall, in part, under the jurisdiction of Member States. After being consulted by the Commission, the European Union Court of Justice[10] pronounced on the free trade agreement with Singapore, which could only be signed jointly by the Union and its Member States, in view of clauses linked to indirect foreign investment and to the settlement of disputes.

In answer to this, the Commission has suggested splitting the trade agreement in two. On the one hand there will be purely commercial provisions, which require only the Union's agreement in order to come into force. These are anti-dumping rules, customs duties, non-tariff barriers, etc. On the other hand, an investment agreement will have to be ratified by all parliaments because these provisions fall under national jurisdiction. This may concern guarantees given in case of legislative modifications to ensure that investments made by foreign countries cannot be challenged, the limits of investments to protect certain sectors or the competent courts in case of dispute. One must expect greater rigidity by partners on the commercial aspect of agreements due to the fact that some of the agreements risk not being ratified nationally, which may weaken the Union's position during trade negotiations.

Reciprocity in the opening up of public contracts

In addition to agreements that have been negotiated or are currently being negotiated, in January 2016 the Commission proposed a new tool in answer to the protectionism of numerous countries outside the Union, which unilaterally do not allow European companies to access their public contracts. Companies from these protectionist countries could, in turn be disadvantaged in tenders published within Member States. However, this proposal is yet to be adopted.

An innovation, the multilateral investments court

In answer to the concerns of NGOs, in March 2018 the Council adopted guidelines authorising the Commission to negotiate, in the Union's name, an agreement setting up a multilateral court responsible for settling disputes involving investments. In the long term this would replace bilateral jurisdictional systems based on the following principles:

- The court must be a permanent international institution;

- Judges must have a fixed mandate, be duly qualified and receive a permanent salary. Their impartiality and independence must be guaranteed;

- Procedures brought before the court must be carried out with transparency;

- It must be possible to appeal against a decision made by the court;

- Effective execution of the court's decisions must be a fundamental element;

- The court must rule on disputes arising within the context of future and existing investment treaties that countries decide to submit to its authority.

Based on this mandate, the Commission will commence negotiations with its trading partners within the context of the UN Commission on International Trade Law.

III - Increasing impact of a concept: a Europe that protects

Initially mentioned by Jean-Claude Juncker in his speech on the state of the Union in 2016, the concept of a Europe that protects appears to have come a long way and is now used increasingly frequently.

Europe already protects in many different ways its citizens, its consumers, its farmers, its businesses, data and individual freedoms, the rule of law, borders and internal peace. It protects both from risks in terms of food safety, health, security, the environment, economic and agricultural risks, social and fiscal dumping and the problems of globalisation. It must now do so better and develop the expected new policies.

Major progress in terms of European defence

In terms of defence, the Commission has gone as far as the treaties allow it[11]. It has responded to a need, playing a central role in recent progress (the creation in 2017 of Non-executive Military Planning and Conduct Capability within the EEAS, the implementation, in December 2017, of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), bringing together 25 Member States). Indeed, in accordance with its president's wish to make the European executive "more political", in November 2016 the Commission presented its European Defence Action Plan and proposed the creation of a European defence fund in order to "support investment in joint research and development of defence equipment and technology[12]", "the promotion of investments in SMBs, start-ups, medium-sized companies and other suppliers to the defence industry" and "the strengthening of the singe defence market".

In 2017 the European Defence Fund was launched, with two aspects, "research" and "capacities" receiving annual amounts of €500 million and €1 billion respectively for the period 2020-2027. Also, within the 2021-2027 multi-annual financial framework, €13 billion is to be dedicated to industrial defence policy.

All this progress is in a direct line from the vision presented by Jean-Claude Juncker in 2014: "Even the greatest peaceful powers cannot ignore the need for integrated defence capacities". It remains to see what competencies the Commission would like to appropriate in the management of the European Defence Fund. For the first time, and contrary to what the treaties say, the Union's budget will be able to contribute to the defence effort made by Member States!

Civil protection mechanisms

To respond specifically to natural catastrophes, the Union's civil protection mechanism can come into play. To date 34 countries contribute to it. In 2017 and 2018, it was activated 52 times. A new reserve of capacity, known as RescEu (comprising helicopters and water bombers) came into being in May 2019. A transition phase also allows Member States to benefit from financial aid when they provide their material resources. It should enable every type of emergency to be dealt with: medical, chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear.

Data protection and cybersecurity regulation

The general personal data protection regulation (GDPR) came into force in May 2018 and is truly innovative. It replaces 28 different national procedures, with a planned optimisation saving of 2.3 billion per year at Union level. It covers right of access, rectification, portability and digital oblivion, such that personal data is not the object of commercial transactions unknown to its "owners". This regulation is a source of inspiration for countries outside the Union (Argentina, Canada, India, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand and Uruguay). Mention can be made of a complaint brought at the end of May 2018 to the French National Computerised Data and Freedoms Commission (CNIL) which resulted in a record fine of €50 million for lack of transparency, unsatisfactory information and the absence of any valid consent for the personalisation of advertising. These offences, which were still in place at the beginning of 2019 justify the size of the penalty.

The rules on respect for private life on line are yet to be reviewed, however: citizens' communications can be read by on-line service providers without their consent whenever they fall outside of the GDPR framework.

We must to refer here to the proposed directive on copyright already adopted in March 2019[13].

Moreover, to support Member States in the combat against threats and attacks in terms of cybersecurity and to establish a European certification framework that will reinforce the cybersecurity of on-line services and mechanisms open to the general public, in 2017 the Commission proposed a legislative act that was adopted by Parliament in March 2019.

IV - The European Commission: prospects and challenges

A -Prospects for adjustments

Future shape of the Commission

As a reminder, the president of the European Commission and the College of commissioners are designated by the European Council and their appointment is approved by a majority vote in Parliament "taking into account the results of European elections". In 2018 European political parties again, for the most part, designated their Spitzenkandidat. The EPP won the greatest number of seats again in May, but this time a coalition with the PES alone will not be sufficient to have a majority in the Parliament, at least 3 groups will have to form an alliance[14].

Derivatives of comitology

Legislative acts can be supplemented by "secondary" acts, which come under procedures known as "comitology". There are:

- Delegated acts: The Commission's powers result from an authorisation specifically mentioned in the legislative texts adopted by Parliament and the Council, which can revoke the Commission's proposal or simply block the act to be produced;

- Execution acts used in case of a need for uniform application of a legislative text in the Union, which cannot be left to the appreciation of each Member States in application of the principle of subsidiarity. In this latter case, the Commission must seek the advice of a committee of national experts (generally according to the rule of qualified majority).

The scope of certain delegated and execution acts proposed by the Commission is challenged notably because they exceed either its "mandate" or its competency. Substantial elements in the initial act may thus be affected by this comitology phase. In the absence of a majority within the committee, the Commission can take the decision alone. According to certain NGOs it often decides against the principle of precaution in cases where opinions from scientific committees consider that no danger can be proved. These detractors from comitology believe that the interests of industry benefitted from these decisions to the detriment of the interests of consumers, notably in terms of health. In February 2019 the Commission therefore proposed:

- To make votes public;

- To be able to take matters to the Council, when cases are blocked;

- To no longer include abstentions or absences in the calculation of qualified majority. To date they have been considered to be a vote against. The reverse will now be true.

This proposed reform has yet to be adopted however.

A new European prosecutor to alleviate the limits of the European anti-fraud office

In a special report published in January 2019, the European Court of Auditors evaluated the efficiency of the Union's anti-fraud policy. In 2017, the amount of fraud detected amounted to only €390.7 million, i.e. 0.29% of all payments made from the European budget.

The Court of Auditors "does not have exhaustive information regarding the scale, nature and causes of fraud". Its statistics on detected fraud are incomplete and undetected fraud has not been estimated. This lack of information has a negative effect on the Commission's anti-fraud strategy, and on the prevention of corruption.

Moreover, the efficiency of the OLAF, which is responsible for administrative enquiries that often lead to criminal enquiries at national level, is challenged:

- The length of procedures reduces the chances of prosecution (only 45% of cases result in prosecution);

- OLAF's final reports sometimes lack information, which prevents the recovery of European funds that have been unduly paid over (less than a third of these amounts are recovered).

In November 2017, the European Union adopted a regulation aimed at creating a European Prosecutor, responsible for combating major cross-border crime affecting the Union budget. The Prosecutor's competency will be limited to offences falling within this field of application. Also, it will be operational in only the 22 Member States[15] which have currently decided to participate and should commence its activities at the latest by the beginning of 2021. This will increase the number of prosecutions and enable more efficient recuperation of funds obtained fraudulently by getting around national and European rules, estimated at several billion euros[16].

With jurisdiction for criminal enquiries, it will carry out its functions completely independently, in the interests of the Union and will neither ask for nor accept any instructions from European or national authorities. It will operate as a single prosecutor for all participating Member States, outside the framework of existing institutions. The European Parliament has already asked for its jurisdiction to be extended to include cross-border terrorist offences.

Alongside this, the OLAF will continue to carry out administrative enquiries into irregularities and fraud that are harmful to the Union's financial interest in all Member States. Within this context, it will consult the European prosecutor and will work in close collaboration with it. This distribution of jurisdiction will result in greater protection of the Union's budget.

B - Priority projects

The budget or pluriannual financial framework (PFF) 2021-2027

The UK's departure will de facto lead to a loss of contribution estimated at between €12 and 14 billion per year. The only consolation is the fact that this departure puts an end to the discounts granted to that country and to those granted to Member States in compensation (discounts on discounts). The Commission has announced, with an equivalent perimeter of 27 Member States, a ceiling figure for commitments of €1 279.4 billion (current prices) or €1 134.6 billion (constant 2018 prices). This represents 1.11% of the Union's gross national income (GNI) for 2021-2027, i.e. a rate slightly below the level of 1.13% for 2014-2020 even when the European Development Fund is included.

Through resolutions the European Parliament has demonstrated its belief that this level of commitments lacks ambition; MEPs would like to see it at 1.3% of GNI. But that level is judged not credible by the European Council, in view of the demands of Member States. Indeed, contributions are considered to be too high by some of them (Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark) and, conversely, insufficient by others.

In order to be able to maintain this level, new resources of the amount of €22 billion (i.e. 12% of income) have been mentioned as a supplement to national contributions: customs duties collected in the Union (reviewed upwards thanks to the reduction in collection costs) and VAT. This is the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB - cf. tax harmonisation) and a tax on non-recycled plastic, which must however first be the object of a legislative vote. Finally, it is proposed to re-affect 20% of national income from the national emissions trading system (of greenhouse gases). The Commission proposes to direct the Union's financial intervention in terms of added value, notably in areas where a Member State does not have sufficient impact to act alone. Thus, the accent is put on:

- The management of migrations and border control (multiplied by 2.6 compared to 2014-2020) which results notably in an increase in the numbers of

border guards, from 1 200 to 10 000;

- Defence and security (multiplied by 1.8);

- External policy (multiplied by 1.3);

- The environment (multiplied by 1.7 directly and multiplied by 1.6 indirectly when including climate questions), such that €1 in 4 spent will be dedicated to action on climate change;

- Research, innovation & the digital economy (multiplied by 1.6);

- Youth (multiplied by 2.2).

In a search for overall efficiency, traditional policies such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the cohesion policy, which still represent most of Union spending, will be modernised, whilst seeing the amounts allocated to them reduced respectively by 5%, and from 6 to 7%. Restructuring into 7 new sections, as well as the difficulty in reading amounts depending on whether they are in constant or current prices, do not allow for easy measurement of developments in the limits of a same policy between the future CFF and the current one. In 2018 this led to reaction in Parliament, which disputed variations, which it estimated at -15% for the CAP and -10% for cohesion policy, a level of reduction relayed by the regional Committee. As for Erasmus, the former proposed a doubling of commitments which the latter denounced in favour of a tripling. Added to these financial frameworks is a star measure, which is the protection of the rule of law via a mechanism for suspending funds. In view of the current political situation, notably in Poland and Hungary in terms of the independence of the legal system and freedom of the press, one may wonder, nevertheless about the probability of unanimous adoption of a CFF that promotes such a measure.

The implementation of flexibility instruments is also planned in order to be able to:

- Respond to emergency situations with the "Union's new reserve fund";

- Support economic and social convergence;

- Stabilise investments;

- Have an impact on the international stage.

An effort is made for European citizens and users:

- By simplifying subsidy formalities for beneficiaries;

- By reducing the number of programmes from 58 to 37, as well as the number of tracking indicators.

The various proposals are made in the new regulation fixing the CFF. The European Parliament can approve or reject these proposals without however being able to amend them. In turn, the Council will adopt this regulation unanimously, or not. The European Council intervenes only through the orientations that it expresses to the Council within the context of negotiations with Parliament.

Jean-Claude Juncker had expressed the wish to see this adopted before the European elections held in May. With the forthcoming renewal of the institutions a challenge to the CFF 2021-2027 proposals is to be envisaged. Might the ultimate proposal of aligning in the long term the duration of the CFF with the five-yearly political cycle of the Parliament and the Commission be a solution to avoid this type of situation? Unfortunately, this is not yet being considered.

Fiscal and social harmonisation

Numerous proposals for fiscal modernisation by the outgoing Commission are still under negotiation. With regard to corporate tax, a common consolidated corporate tax base (CCCTB)[17] would permit financial optimisation for companies, fairer competition and less tax evasion. In terms of value-added tax (VAT), the creation of a single taxation area in the Union would result in a reduction in fraud and therefore an increase in public income. As for digital services, a so-called "GAFA" tax would tax profits according to the "digital" place in which they are made and no longer based on the geographical location of the companies themselves.

Also, rules on posted labour have been harmonised to ensure that for identical work, in the same location, a worker posted from another Member State benefits from the same salary as local workers. And to check on the application of these harmonised rules on mobility, the European Labour Authority has been created. Its aim is to encourage cross-border cooperation in terms of Union law, with joint inspectors and access for stakeholders to their rights, obligations and associated services in this regard. Nevertheless, the interaction of social security mechanisms within the Union will remain complex to the detriment of inhabitants or workers established in another Member State (17 million Europeans in 2017) as long as the proposal put forward by the Commission at the end of 2016 has not been accepted.

Competition

The Competition policy is part of the exclusive competency of the European Union and it is based specifically on two pillars: it aims to protect consumers and it is applied impartially and independently by the Commission[18]. Although over the past few months, following rejection of the Alstom-Siemens merger, it has been the object of lively debate amongst Member States, being reproached specifically for hindering the emergence of large size companies that could rival Chinese and American businesses, one notes above all the measures taken to regulate the digital giants: as an example, in 2017, 2018 and 2019 Google was fined €2.42 billion, 4.34 billion and 1.49 billion respectively for having abused its dominant position. The Commission also fined Facebook €110 million for having provided misleading information during the buyout of WhatsApp, and a fine of €13 million was levied on Apple due to its tax agreements with Ireland. As for the Russian giant Gazprom, to settle concerns in terms of competition in Central and Eastern Europe, in May 2018 the Commission adopted a series of legally restrictive regulations[19].

Although competition remains a major project for the next mandate, after the Alstom-Siemens affair, France and Germany have put forward proposals to reform the law on competition for better protection of European champions.

Deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union

Only modest progress has been made in deepening the Economic and Monetary Union[20], despite the numerous proposals put forward by the Juncker Commission (for example the proposal to create a position of European Economy and Finance Minister, a support programme for reforms and a European investment stabilisation mechanism, etc.). Major work still needs to be done with regard to completion of the Banking Union and the Capital Markets Union, the creation of a budgetary instrument for the euro zone and the creation of a safety net for the Single Resolution Fund.

In 2015, the Commission created the European Budgetary Committee, an independent body that elaborates consultative opinions with regard to the Union's budgetary policies. The Commission has also started to pay particular attention to use of the euro at world level and its international role, an essential aspect in reinforcing European geopolitical power[21].

Natural resources management strategy

In view of increasing dependency on natural gas imports, despite the energy transition that has been started, the Commission initiated modifications to the directive on gas in 2017, which were adopted in 2019, to harmonise rules particularly for suppliers across the whole of the Union's terrestrial and maritime territory.

In terms of drinking water, one of the Commission's proposal remains under negotiation. Its aim is to reduce health risks linked to water to less than 1% of the population compared to the current level of 5% and to guarantee access to water for all, compared to 11% of this same population currently affected by shortages. These measures would enable a reduction in the consumption of bottled water, a source of economy and reduction in the production of plastic waste and the associated greenhouse gas emissions.

***

The legacy of the Juncker Commission is remarkably positive. Within a particularly turbulent geopolitical environment it has been able to adapt, reacting quickly by means of relevant, innovative proposals. It has not hesitated to "go to the limits of its competencies" in order to bring solutions to issues that Member States have shown themselves incapable of dealing with together.

Such is clearly the case in terms of immigration. Without the measures taken by the Commission, the migration wave of 2015-2016 would not have been contained. In other areas it has been able to respond to the concerns expressed by the European Council and offer firm follow-up to its demands. This was the case in terms of Defence and Security, areas that are all too clearly within the competency of States.

Finally, it has carried out its mission with imagination, tenacity and competence. Adoption of the GDPR or the reform of copyright law owe a great deal to its constancy and commitment.

The signing of numerous trade agreements with Canada, Japan and Singapore, as well as negotiations commenced with others, in spite of sceptical opinions and a slow-down in multilateralism amongst some of our major partners, must also be posted to its credit.

In most cases the Juncker Commission has made real the wishes of the European council and the meeting of Heads of State and Government responsible for defining "major orientations" of European policies, and has overcome blockages by the Council, the assembly of ministerial representatives from Member States, often paralysed by the clash of national interests.

In its relations with Parliament, the Juncker Commission has found a more active, more efficient collaboration at the service of European citizens.

The real negative remains, as has been the case for many years, Communication.

For many years forbidden by Member States from communicating itself, and then often paralysed by the idea of angering them, Jean-Claude Juncker himself acknowledged with regard to Brexit, that the Commission had refused to communicate with citizens directly, intelligently and simply.

It could have done so, and must do so. For that several conditions are required:

- Communicate only when there is something to say,

- Communicate only within one's scope of competence,

- Communicate only in the name of the Union and not in the name of the Commission and its services,

- Communicate directly and without a spokesperson.

With this reservation, which is nothing new, it must be recognised that Jean-Claude Juncker has accomplished a positive mandate at the head of the Commission. His personal input must not be under-estimated so attached is he to his vision of a more political European Union, closer to citizens but also more efficient and more reactive to such considerable changes in the geopolitical environment.

A strong and active Commission is essential for the correct functioning of the Union. He has once more just demonstrated as much.

Authors

• Ramona Bloj

Head of Studies, Robert Schuman Foundation

• Cindy Schweitzer

Research Assistant, Robert Schuman Foundation - Master® "Expert in European Public Affairs" (MSEAPE) ENA

The authors would like to thank the entire Robert Schuman Foundation team for its contribution to this publication.

[1] i.e. around 33000 civil servants compared, for example, with 2.427 million staff working in the public sector of the French State (79.9% in ministries and 20.1% in national public administrative authorities).

[2] Independently of new procedures to lodge complaints (Solvit).

[3] IMF Country Report No. 14/151.

[4] EU decisions 2015/1523 of the Council of 14th September instituting provisional measures in terms of international protection in favour of Italy and Greece, and 2015/1601 of the Council of 22nd September 2015 instituting provisional measures in terms of international protection in favour of Italy and Greece.

[5] There is a gap of around 10 percentage points between the shares of LNG imports from the United States at 12%, compared to 2.3% before the joint declaration and since the first cargo of American LNG delivered to Europe in 2016.

[6] http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/september/tradoc_157331.pdf

[7] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-519-fr.pdf

[8] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-503-fr.pdf

[9] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-502-fr.pdf

[10] Opinion 2/15 of 16th May 2017 from the CJEU in response to a request for opinion under the terms of article 218, paragraph 11, EU Functioning Treaty, introduced on 10th July 2015 by the European Commission.

[11] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-474-fr.pdf

[12] The Commission estimates that the lack of cooperation between Member States in the field of defence represents an annual cost of between €25 and 100 billion.

[13] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/doc/questions-d-europe/qe-512-fr.pdf

[14] The number of groups is set to be identical to that in the last parliament.

[15] Germany, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Spain, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

[16] In 2015, for example - in addition to VAT fraud - Member States notified fraud impacting the Union's budget representing an amount of around €638 million.

[17] Without common taxation rate

[18] Sébastian Jean, Anne Perrot, Thomas Philippon, Concurrence et commerce: quelles politiques pour l'Europe? Notes from the economic analysis council, no 51, May 2019.

[19] http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-3921_fr.htm

[20] European Commission - Press release, Deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union: the Commission's report, 12th June 2019

[21] https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/questions-d-europe/0506-pour-une-geopolitique-de-l-euro

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Gender equality

Helen Levy

—

3 March 2026

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :