The EU and Globalisation

Nicolas Goetzmann

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas Goetzmann

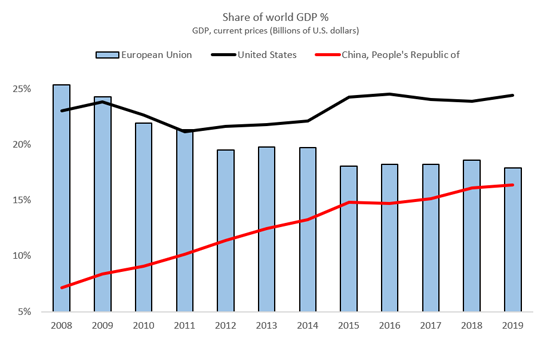

The early 1990s saw the demise of the Soviet bloc, erasing more than forty years of competition with the United States: the rest of the decade witnessed the economic emergence of the People's Republic of China and the formal advent of the euro area as the economic powerhouse of the European Union. Two decades later, according to data published by the IMF, almost 60% of the world economy is now shared between these three dominant economic areas, the United States, China and the European Union, reshaping the face of the competition for global power.

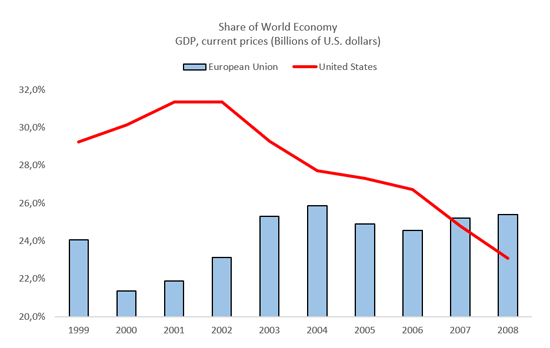

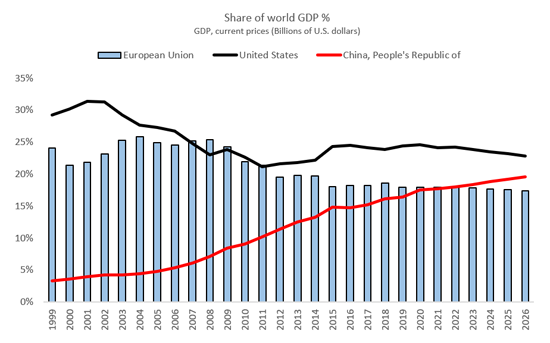

Since the beginning of the millennium, the race between the great powers has been highly volatile, allowing the European Union, in a first phase (1999-2007), to take the leading position in the world economy from the United States, before undergoing, in a second phase (2007-2021), a relative decline that now puts it within reach of being overtaken by China from 2022.

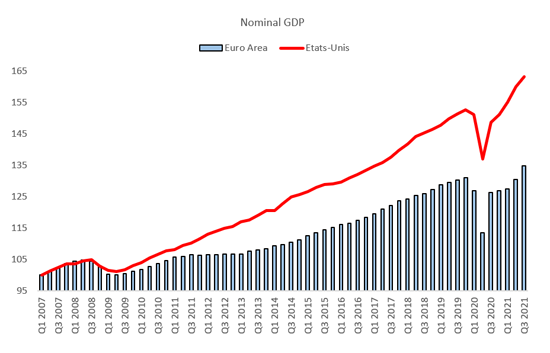

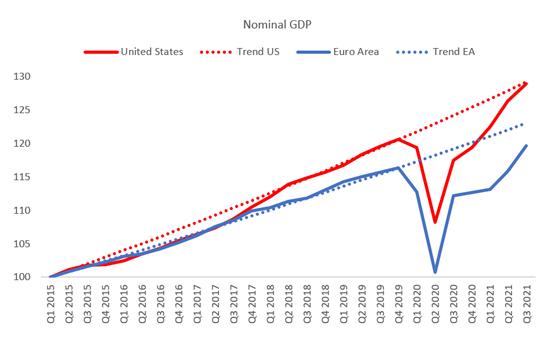

However, this decline was not inevitable. During the initial phase, the euro area saw its growth approach the pace set by the United States. In contrast, while the US economy grew by more than 20% between the great financial crisis and the eve of the pandemic, the euro area only achieved half of that figure. At the same time, the irresistible rise of the Chinese economy took advantage of Europe's underperformance to reach a position in which the latter could be overtaken.

The macroeconomic stability strategy governing the euro area and the European Union as a whole thus proved ineffective during this period of post-financial crisis recovery. At the same time, it became synonymous with relative stagnation for the European continent, in the face of a US economy that managed to maintain its position and twenty years of historic growth for China. The macroeconomic mistakes made in the aftermath of the great financial crisis were the cause of Europe's downward trajectory.

It is in this context that the European Union and the euro area have to review their economic strategy so as to return to a trajectory that will enable their participation in the global economic race following the pandemic crisis and, in this way, prove themselves consistent with an ambition of strategic autonomy that they have now assumed. This transformation is all the more necessary since the context associated with the Covid-19 epidemic places Europe in a phase of recovery, while its economic architecture has already proven its limits in such a configuration.

1999-2007: the euro area's golden age

From its birth to the eve of the great financial crisis, the euro area grew at an average annual rate of 2.33%, while the United States' rate of growth lay at 2.8% over the same period. This was the euro zone's golden age, resulting in the European Union overtaking the United States in terms of global economic weight, particularly thanks to the appreciation of the single currency.

Europe's performance is all the more remarkable given that China's economic weight doubled during these years, rising from 3.3 to 7% of world GDP between 1999 and 2008, without affecting Europe's ability to maintain its position.

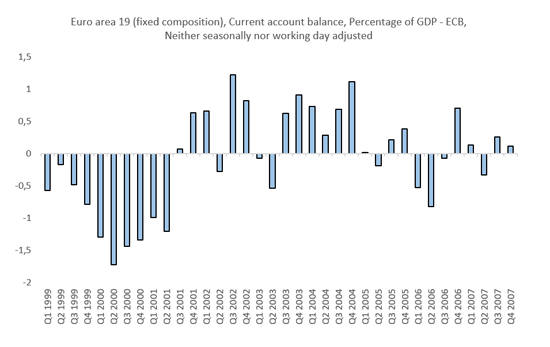

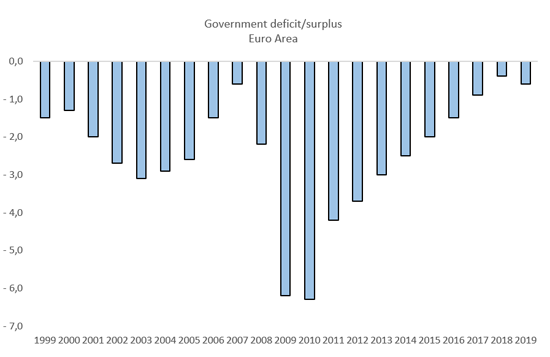

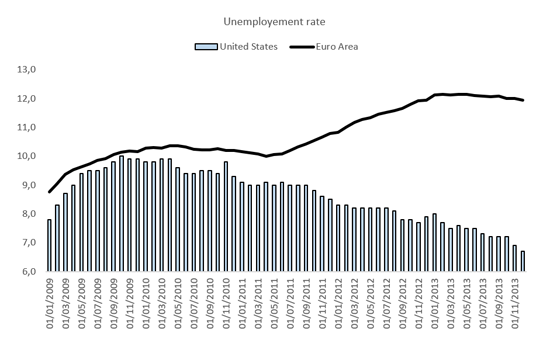

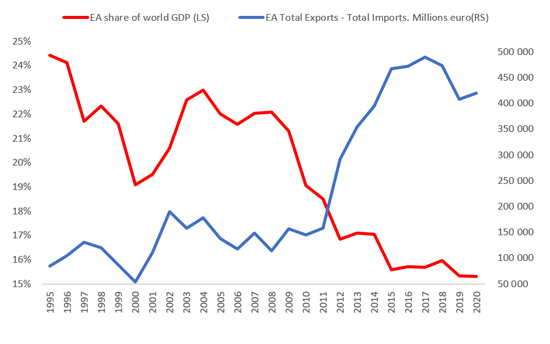

During this period, the unemployment rate in the euro area decreased from over 10% at the beginning of 1999 to 7.3% on the eve of the great financial crisis. Despite some deviations, the European budgetary rules, resulting from the Treaty, did not prove to be particularly restrictive for the Union's governments, which could count on high growth to increase their revenues and balance their accounts. This period also saw the relative stability of the zone's trade balance, which was close to 0% at the end of 2007, a sign of the macroeconomic balance brought about by this decade of growth.

2008-2019: the great financial crisis and its consequences

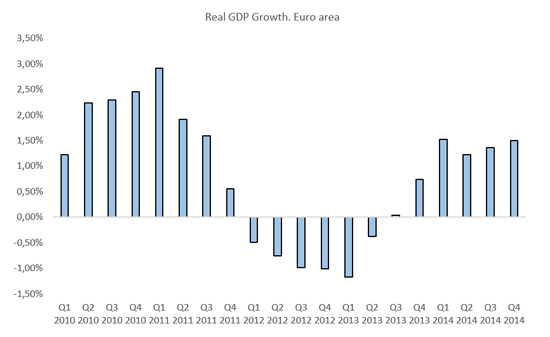

The onset of the major financial crisis in 2008 disrupted the balance of growth. While the United States returned to an average growth rate of 2.2% between 2009 and 2019, i.e. 20% lower than the growth experienced between 1999 and 2007, the euro zone experienced pronounced stagnation from 2011 on.

Over the decade 2009-2019, average growth in the euro area was 1.37%, 40% lower than in the years 1999 to 2007; a decrease of more than twice that recorded in the US. This result was the direct consequence of the European macroeconomic choices made during this period.

In an interview in December 2012, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said[1] : "If Europe represents 7% of the world's population, produces about 25% of the world's GDP, and has to finance almost 50% of total social spending, then it seems obvious that we will have to work very hard to maintain our prosperity and our way of life (...) We all have to stop spending more than we earn each year".

In fact, it was a policy of fiscal austerity, supported here by Angela Merkel, that was to be pursued in the euro zone during the coming decade. A choice that appeared to come in response to an increase in debt that occurred during the great financial crisis.

This choice of macroeconomic austerity clearly contrasted with the words of Hu Jintao[2], then President of the PRC, who announced in August 2012 that he wanted to double his country's GDP by 2020. This was also in contrast to the Federal Reserve's implementation of a new quantitative easing plan in 2012, aimed at accelerating an economic recovery that was deemed disappointing across the Atlantic and yet superior to that experienced in the euro area. The strategic divergence between the major powers was total; Europe chose frugality while China and the United States chose growth.

Thus, from a macroeconomic point of view, a cycle of budgetary restriction began in the euro area, but without this being compensated by expansionary monetary policy. A lack of coordination led to the failure of the European system as a whole. By choosing to reduce the growth rate of public spending by more than 45% between the period 1999-2007 and 2008-2019, Europe permanently undermined its growth without the European Central Bank (ECB) compensating for this movement. From an average nominal growth of 4.4% between 1999 and 2007, the figure fell to 2.02% between 2008 and 2019, i.e. a decline of almost 55%. Large-scale action by the ECB would have enabled an acceleration of nominal growth, which would itself have facilitated the efforts undertaken by Europe's governments. But instead of addressing the debt issue through growth, Europe chose the counterproductive path of a - dry - contraction of domestic demand.

Moreover, the fiscal squeeze that began in 2011 was strengthened by the ECB's monetary restriction measures. On 13 April and 13 July 2011, the ECB raised interest rates twice, despite the fact that GDP in the euro zone was 1.7% lower than its peak in the first quarter of 2008. By comparison, the first rate hike by the Federal Reserve took place in December 2015, when US GDP was more than 10% above its 2008 peak.

The arrival of Mario Draghi at the head of the ECB on 1 November 2011 helped to reverse these decisions before the end of that year, but it was not enough to halt a negative spiral that precipitated what has been unfairly called the "European debt crisis", since it was primarily the result of a strategy. Because of the decisions taken in 2011, growth in the euro area inexorably sank into the negative.

The dual action of macroeconomic, fiscal and monetary contraction witnessed the decline of the euro area - and the European Union with it - in their global economic weight as of 2008.

Although the European unemployment rate had begun to fall as of April 2010, dropping back below 10% in April 2011, it began to rise again the following month, reaching over 12% in 2013.

The relative weakness of the European economy was matched by an increase in its trade surplus, which might ironically be seen as a symptom of the continent's decline. The weakness of European domestic demand appeared to be the driving force behind the build-up of the surplus, compared to exports that were dependent on demand from the rest of the world.

For example, the strategy implemented within the euro area in the aftermath of the great financial crisis resulted in the continent losing its position as world economic leader to the United States, while second place might be lost to China as early as 2022, according to IMF projections.

In her interview with the Financial Times on 16 December 2012, Angela Merkel says: "We saw in the GDR and throughout the socialist system that an economy that was no longer competitive prevented people from prospering and ultimately led to great instability." She added: "I find it worrying that many people in Europe simply assume that, alongside the US, Europe offers the only frame of reference for the world - that Europe is traditionally strong and that the world looks to us (...) Other models have long since emerged: China, India, Japan, Brazil, and they will be joined by other countries that work hard and are innovative at the same time."

Paradoxically, it is by contracting its macroeconomic policy, by choosing austerity and "seriousness" - both at the budgetary and monetary level - in pursuit of a policy of competitiveness, that the European continent has experienced a relative decline in world GDP, notably to the benefit of China, while at the same time eroding the global influence of its model.

Europe's downward trajectory was halted, however, when the ECB introduced a quantitative easing plan in January 2015. But while the recovery of the European economy has allowed a return to stronger growth than in the previous five years, the effort has not been sufficient to make up for the losses accumulated since the great financial crisis.

2019-2022: the start of a new strategy

As the ECB ended its quantitative easing programme at the end of 2018, a deceleration of growth in the euro area was again apparent. To address this, Mario Draghi decided in September 2019 to implement a new plan of the same type.

In January 2020, Christine Lagarde, the new President of the ECB, initiated a review of European monetary policy with a view to updating a strategy whose results had been clearly sub-optimal over the previous decade. Thus, the drive for a macroeconomic reorientation of the continent appears to predate the pandemic.

Similarly, an exercise to "review" US monetary policy began at the end of 2018, for comparable reasons and with the aim of maximising US growth over the next few years. But in both cases, the "review" process was hit by the spread of the Covid-19 epidemic, which precipitated the implementation of a new macroeconomic approach in the West. Indeed, learning from past mistakes, the US and the euro area have committed to historically large-scale support for their economies through fiscal and monetary initiatives.

Thus, in July 2020, the European Union agreed on a coordinated continental level fiscal stimulus plan to the tune of more than €750 billion, in addition to the various stimulus plans implemented by each of the Member States. Similarly, the ECB has been implementing quantitative easing since March 2020, bringing the total amount of securities repurchases to €1,850 billion in support of the European economy.

These measures will help the two continents achieve a historic economic recovery concomitant with the publication of new monetary strategies by the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

As of August 2020, the Federal Reserve (Fed) adopted a Flexible Average Inflation Targeting strategy, with the aim of promoting a maximum employment situation that it felt had been ignored too much in the past. In this perspective, the Fed is adopting a "high-pressure" economic regime strategy which can also be seen as a response to China's ambition to overtake US GDP by the year 2030.

In Europe, the ECB announced the content of its new monetary policy in July 2021: a symmetrical inflation target of 2% replaced the "below but close to 2%" inflation strategy in force since May 2003. While this policy is clearly more expansionary than the previous one, it is still behind the one implemented in the US.

By the third quarter of 2021, US GDP was back on its pre-crisis path, something it never managed to achieve in the aftermath of the great financial crisis. For its part, and despite a result well above that recorded during the 2008 crisis, the euro zone is still 3% below this trend, and the ECB's current forecasts for 2024 do not suggest that this gap will close.

To avoid repeating past mistakes and with the aim of placing the continent in a phase of growth more in line with its potential, the national and Community monetary and budgetary authorities must pursue a policy of maximum support for the European economy over the next decade. Thus, the macroeconomic efforts made during the pandemic phase must become more structural than cyclical. Moreover, as a matter of priority, European macroeconomic policy must better articulate its fiscal and monetary policies, the latter being the most effective tool for complying with budgetary rules.

***

Either through the reshaping of the European monetary strategy, or through a new fiscal approach - the outlines of which will be drawn up in Paris[3] on 10 and 11 March 2022 during an exceptional summit devoted to the "new European growth model" - and their necessary coordination, the European Union can articulate its economic development model with a "high-pressure" growth strategy. While the Chinese economy will face the deceleration of its own growth, sluggish demographics and a necessary change in its development model, Europe has the opportunity to position itself favourably in the competition over the next decade, in line with its ambition for strategic autonomy.

In March 2021 American President, Joe Biden[4], described the competition taking place between China and the United States: "China has a global goal, and I'm not criticising them for that goal, but they have a global goal of becoming the leading country in the world, the richest country in the world and the most powerful country in the world. That's not going to happen on my watch because the United States is going to continue to grow and expand."

In this competition between Chinese authoritarian power and American democracy, the European model has a considerable asset to put to the benefit of liberal democracy: a social model that can neutralise the Chinese attacks on American inequalities.

If the durability of this model was undermined during the 2010's and was considered by Angela Merkel to be one of the continent's weaknesses, this European particularity now appears to be a strength and a bulwark, provided that it is supported by a "high pressure" growth strategy. If the continent succeeds in articulating its welfare state with maximum growth macroeconomic management, then Europe will have the most promising model of the next decade.

Indeed, as the Biden administration struggles with Congress to deliver on the President's social promises, seeking to reconcile foreign policy with middle class interests, the welfare architecture that the European continent has is emerging as a model for the future. A model that requires the continent's authorities to abandon a macroeconomic strategy of stability, which has proved to be synonymous with stagnation, in favour of a strategy of "maximum" growth, which would strengthen European domestic demand, balance the continent's balance of trade, rebalance its overdependence on exports and, in this way, place the continent in a position of strategic autonomy.

[1] Merkel warns on cost of welfare, Financial Times, 16 December 2012

[2] Hu's Goal for China: Double Incomes by 2020, Bloomberg, 8 November 2012

[3] Presentation of the French Presidency of the European Union. 9 December 2021

[4] Remarks by President Biden in Press Conference 25 March 2021

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

Strategy, Security and Defence

Jean Mafart

—

27 January 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :