Economic and Monetary Union

Nicolas Goetzmann

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas Goetzmann

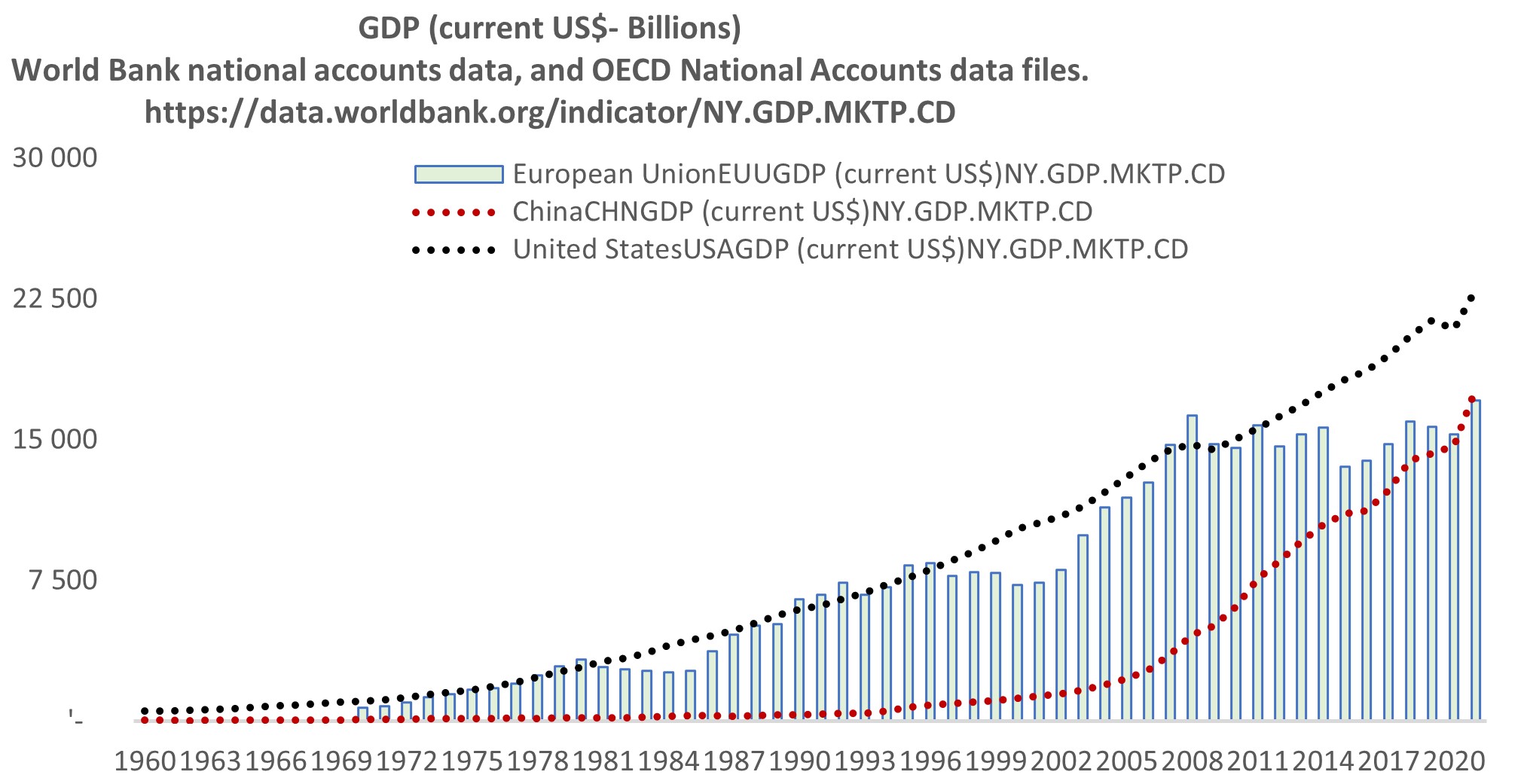

The succession of shocks that have hit the global economy since the beginning of 2020 highlights the strengths and vulnerabilities of the different growth models of the major global blocs, namely the United States, China and the European Union[1].

While the United States can still count on domestic consumption, which is the unsinkable foundation of the country's development, China faces the necessary evolution of a model considered obsolete by its authorities[2]. From growth guided by a level of investment that will be difficult to sustain over the long term and a trade balance that is largely in surplus, Xi Jinping's China is under increasing pressure to support its domestic demand as a means of correcting its imbalances. Situated at the centre of this Sino-American competition, the European Union - and more precisely its heartland, the euro area - finds itself weakened by sluggish domestic demand and development based largely on foreign trade, the structure of which has been geopolitically undermined over the last three years.

However, the shortcomings of the European growth model came to light in the aftermath of the great financial crisis, which pushed the GDP trajectory onto a path of stagnation, the first consequence of which was that it fell behind the United States, before being overtaken by the Chinese economy in 2021.

It is in this context of upheaval in the global economic hierarchy that inflation started to rise at the end of 2021 - before worsening in 2022 and undoubtedly in 2023 as well - and that the economic authorities, led by the European Central Bank, ran the risk of persevering with a model that had become synonymous with relative decline, which was by no means inevitable.

The fragility of the European economic model

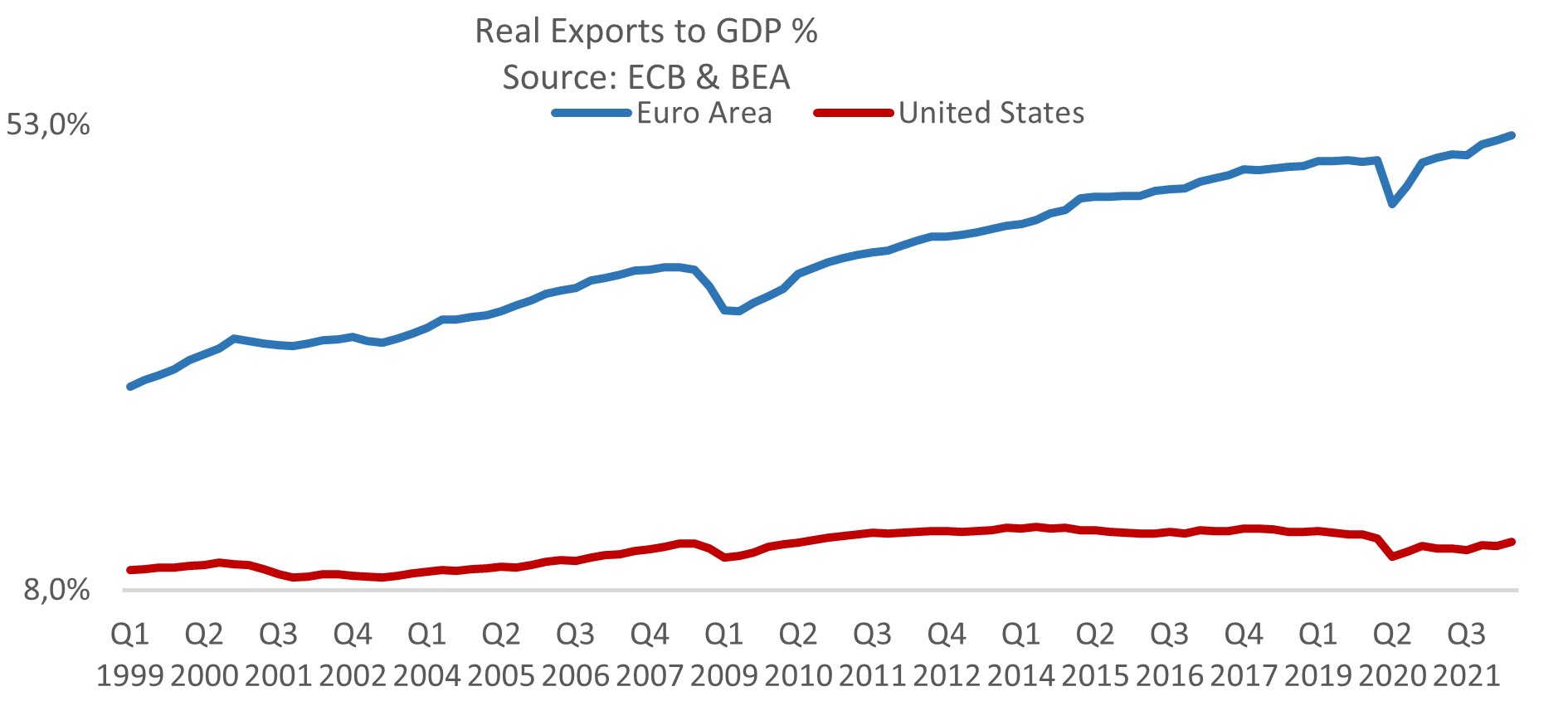

The European economic model can be measured by its results. Between 1999 and 2022, the share of exports rose from 29% to 52% of GDP in the euro area, while imports increased from 28% to 48% of GDP over the same period. By comparison, exports account for less than 12.7% of US GDP, and data published by the World Bank indicate that they will account for only 20.7% of Chinese GDP in 2022, compared with 18.2% in 1999.

Compared with the other two blocs, the USA and China, the euro area is characterized by an overexposure to trade. Remarkably, in the first quarter of 2023, the economic weight of its exports (1,544 billion) was greater than that of household consumption (1,534 billion), i.e. a ratio of 100.7% versus 20.3% in the USA. The euro area exports more than its households consume, while American households consume five times more than the country's total exports.

In 2018, a record trade surplus of more than €500 billion was achieved by the euro area over its economic partners. In contrast, in the same year, the United States’ trade balance lay in deficit of almost $580 billion. This divergence between the two continents is further revealed by the evolution of the American trade deficit with the European Union since the advent of the euro area; while it was $29.3 billion in 1999, it rose to $148.5 billion in 2021, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

However, this European export "performance" has been achieved at the expense of the continent's domestic demand. Indeed, the export performance and the quality of European goods and services do not suffice to explain the constitution of such trade surpluses. These surpluses have been achieved through the relative weakness of European domestic demand: the more the continent exports, benefiting from the strength of global growth, and the less it consumes in relative terms, the larger the trade surplus will mechanically be.

Between the end of 2007 and the end of 2013, the export of goods and services from the euro area grew by 9% while imports only grew by 1.7%. This gap automatically led to an increase in the trade balance, which tripled during this period to reach a share of nearly 5% of the euro area's GDP. In fact, the constitution of the European trade surplus is the result of an internal weakness that prompts questions

Sluggish domestic demand

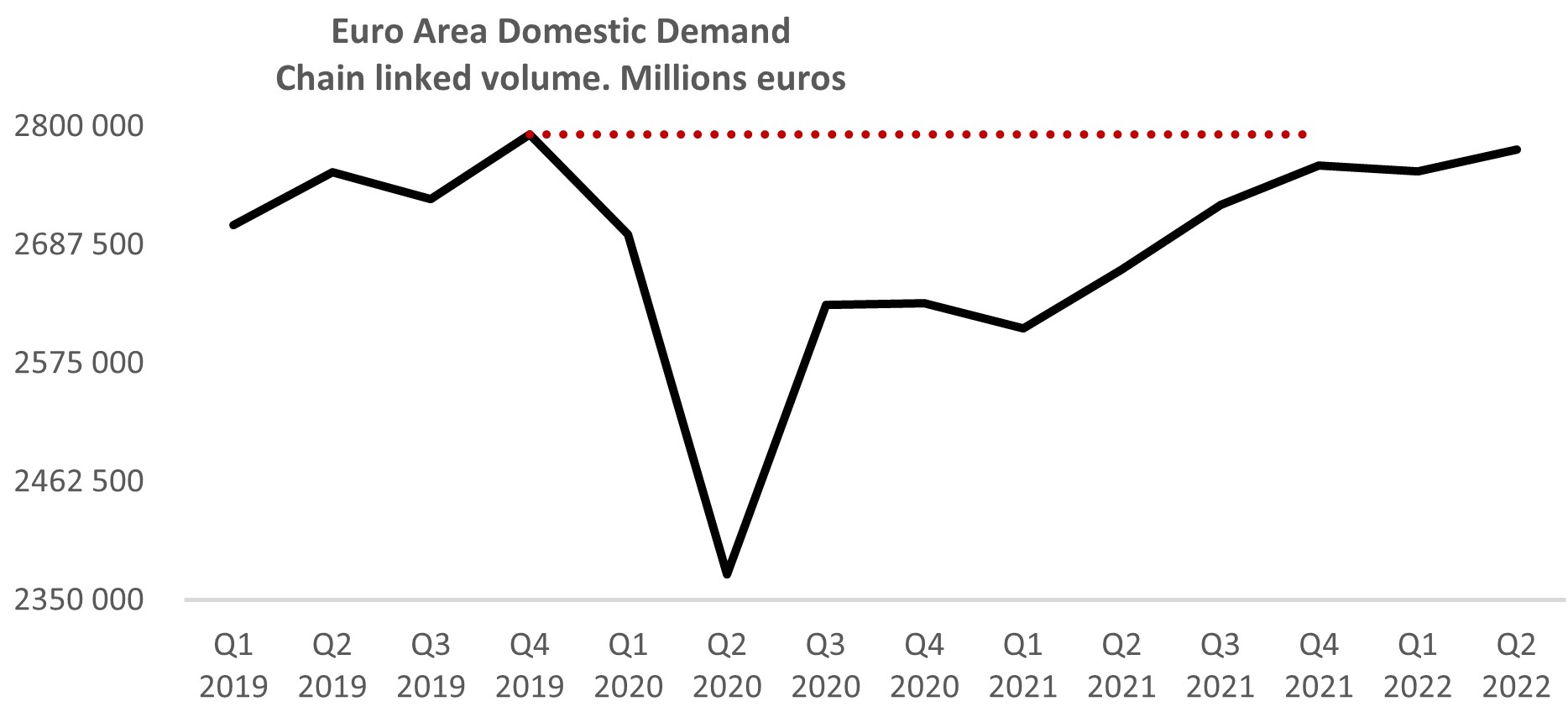

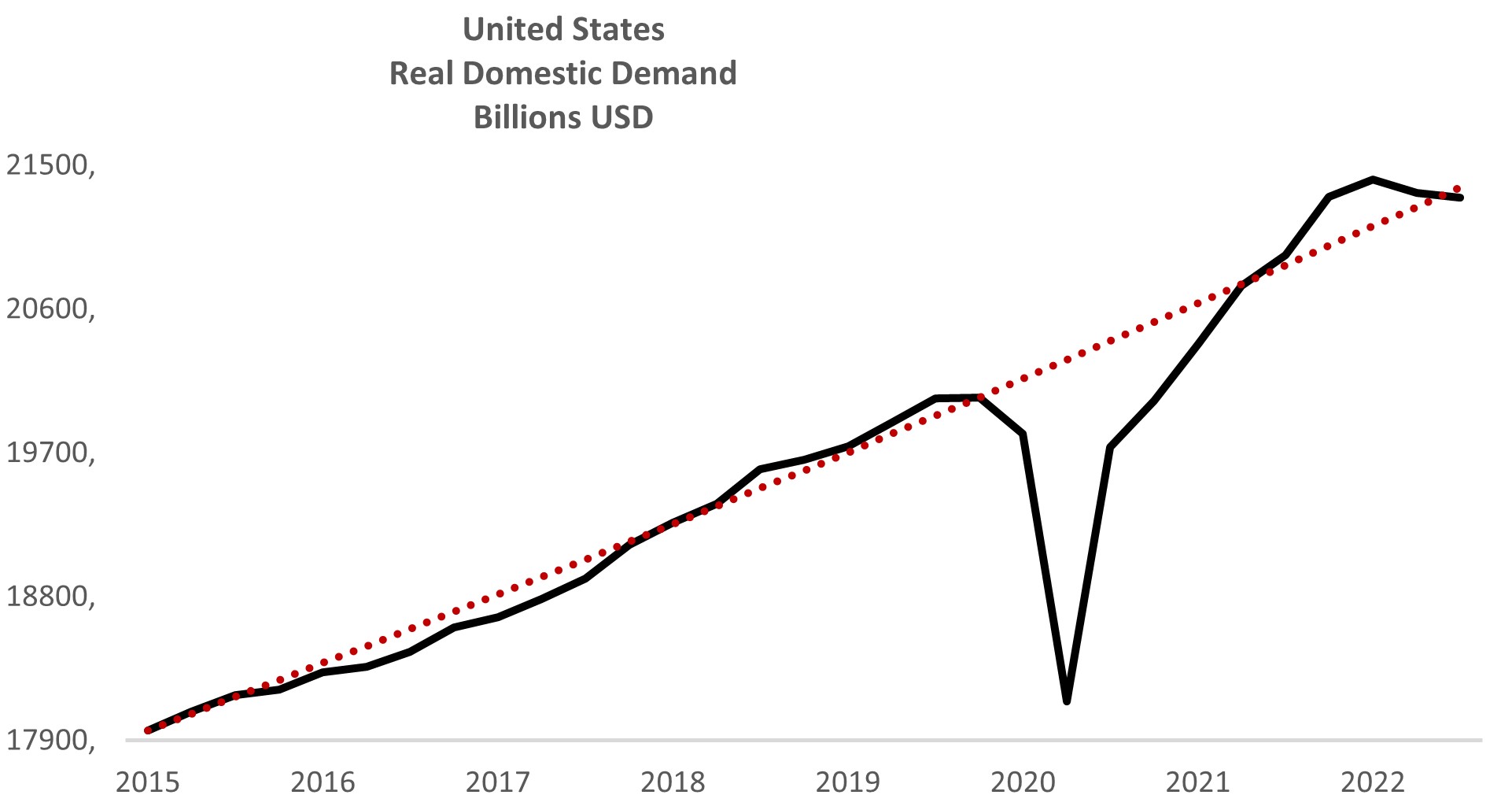

As the euro area has developed, between the first quarter of 1999 and the second quarter of 2023, euro area domestic demand (comprising consumption, investment and inventories) grew by 30.1% compared to a 67.1% increase in the US. US demand for the global economy has thus grown more than twice as fast as demand from the euro area. Since 2008 and the great financial crisis, this trend has become more pronounced, with US demand growing three times faster than demand from the euro area. This context makes the American market the object of great envy, relative to a sluggish European market.

The weakness of domestic demand is not the result of fate, but of macroeconomic policy. Whether through the Stability and Growth Pact aimed at limiting budget deficits or through the price stability mandate of the European Central Bank, the macroeconomic design of the euro area is geared towards a restrained outcome of this nature in terms of European domestic demand, which is mainly reflected in wage growth.

For the euro area, the average compensation per employee adjusted to inflation increased by 10.3% between 1999 and 2022, in contrast to 31.7% in the US. This is due to low wage growth in the euro area, the downward trend in hours worked, but also to the high rates of inflation in recent months. This situation is preventing the European domestic market from being seen as a base for the development of its companies, unlike the United States.

Unlike the US, which treats wage growth as a priority source of growth, the European approach to wage moderation is part of an export competitiveness strategy. But this approach has led the euro area down a path of declining relative geopolitical weight, increased vulnerability to China and Russia, and a weakening of its employed population with a sustained stagnation of income, which is also threatening the continent's political stability.

In her inaugural speech as head of the European Commission on 27 November 2019, Ursula von der Leyen said: "It is a geopolitical Commission that I have in mind, and that is what Europe urgently needs”.

While Ursula von der Leyen's geopolitical ambition makes sense in the light of the events that followed this statement - from Covid-19 to the Russian aggression in Ukraine, to the extraordinary surge in Chinese automobile production - her use of the term "competitiveness" nine times in the same speech marks a profound paradox. It is indeed this model of competitiveness, which has led Europe to become highly dependent on those external markets; from Chinese demand to energy supplies from Russia, which are also considered to be more 'competitive'. This model is also the primary cause of massive European under-investment, a circular consequence of the low growth it generates.

A clear awakening in the midst of the pandemic

In response to the risk and uncertainty caused by the outbreak of the pandemic in early 2020, the world's major economic areas reacted vigorously. Building on past experience of unsatisfactory economic recovery in the aftermath of the major financial crisis, Europe and the United States have managed to produce historic stimulus packages, both from a fiscal and monetary perspective.

Whether it was through an initial large-scale response by the European Central Bank or through the agreement reached by European capitals in July 2020 to support the European economy through the €750 billion NextGenerationEU plan, the European Union seemed to be learning from the past to deal with the difficulties it was now encountering.

Continuing a similar approach, in July 2021, the European Central Bank published the results of its "monetary policy strategy review", modifying its quantitative definition of its inflation target, which allowed for greater structural support for European domestic demand.

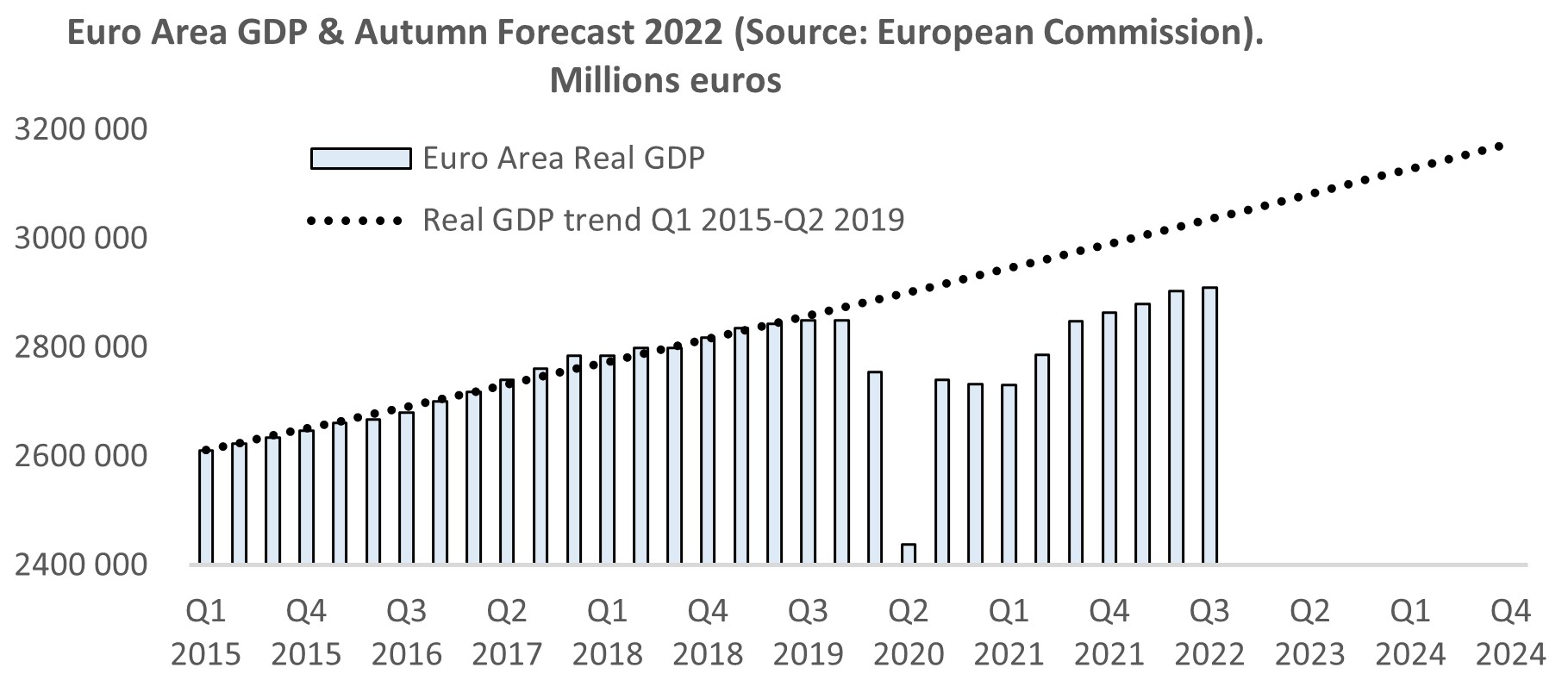

In the aftermath of the great financial crisis, it took 28 quarters for European GDP to return to its pre-crisis level. In the aftermath of the pandemic, 8 quarters have been enough to achieve this result, demonstrating the effectiveness of the strategy adopted during this crisis.

As the two arms of macroeconomic policy have converged according to the logic of a strong economic recovery in the wake of the pandemic, the hope that such a strategy would be structurally embedded in the DNA of the European economic model has taken shape. This favourable outlook has been challenged by the onset of inflation.

Rising inflation is threatening Europe's recovery

Despite Europe's economic recovery, which was expected to be much stronger than its post-2008 precedent, the inflationary surge that began in the summer of 2021 led the European Central Bank to revise its approach initiated during the pandemic and to announce a phase of monetary tightening which, combined with the inflationary dynamic, has already had a recessionary impact on European domestic demand.

In the first quarter of 2023, household consumption in the euro area reached a level 0.6% below that of the last quarter of 2019, signalling over three years of stagnation, while US households saw their real, inflation-adjusted consumption grow by 9% between the end of 2019 and the second quarter of 2023.

While this response by the European Central Bank seems to be justified by the inflation level that was in excess of 10% in the last months of 2022, the nature of the inflation affecting the euro area could justify some restraint on the part of the European monetary authority.

In fact, unlike in the United States, where a situation of strong domestic demand justifies the Federal Reserve's response, this phenomenon has not been observed in the euro area, indicating that the excess inflation is not the result of excessive domestic demand.

And yet in an article published on 10 February 2022, Philip Lane, Chief Economist for the European Central Bank, said “Since monetary policy steers domestic demand, a tightening of monetary policy in reaction to an external supply shock would mean that the economy would be simultaneously confronted with two adverse shocks - a deterioration in the international terms of trade (generated by the increase in import prices) and a reduction in domestic demand”[3]. It took only a few weeks for this warning to be contradicted by a change in the balance of power within the ECB, leading to a monetary tightening policy of historic speed and magnitude.

The ECB's current strategy is leading to a slowing in European domestic demand, which was already visible in the third quarter of 2022.

At the same time, US domestic demand is exceeding its pre-crisis level by more than 8%, indicating that US recovery has succeeded in erasing the traces of the pandemic on its economy, despite average inflation of more than 8% during 2022.

What alternative to the European growth model?

The European growth model might have been considered particularly suitable for the first two decades of this new century, typified by the boom in international trade. However, this model has proved to be counterproductive both for Europe's populations, who have suffered stagnation in their labour incomes, in terms of GDP growth, which is the result of a structural weakness in the continent's domestic demand. This weakness has also led to a profound underinvestment in Europe. Between the last quarter of 2007-2008 and the first quarter of 2023, European investment (apart from Ireland) grew by 4.6% compared to 36.8% in the United States, leaving little room for future potential growth through innovation.

While Europe's strategic ambition is now based on the notion of strategic autonomy, political urgency must focus on the need for a substantial change in its economic model. This strategic autonomy is indeed antinomic with a development model whose foundation is based on external demand, and its corollary which has been its internal weakness.

To meet a requirement of this nature, a macroeconomic model committed to restoring and structurally supporting the continent's domestic demand would offer the best guarantees. Indeed, by further supporting its internal growth, the European continent would then have the opportunity to provide its companies with a robust market, just like the American companies. Such support for domestic growth would then mechanically reduce Europe's vulnerability to external demand while allowing an increase in the population's labour income.

The result of such a strategy would then be to support European growth in a structural way, to trigger an increase in investment and an increase in future growth potential. Finally, the increase in tax revenues would then be linked to growth and thus offer greater budgetary room for manoeuvre to euro area governments.

Whether it is for the benefit of the people of Europe or for the benefit of the continent in terms of relative strength, the need for a change in the European model must be considered a priority. While the European economic model has been built on a monetary policy strategy focused exclusively on price stability, an economic model of domestic demand requires a change in the approach adopted by the European Central Bank, so that it is now guided by the pursuit of maximum potential growth and full employment.

Head of research at the asset manager Financière de la Cité

[1] This text was originally published in " The Schuman Report on Europe, the State of the Union 2023 " éditions Marie B, Paris, May 3, 2023. It has been updated.

[2] China’s Dependence on the Property Sector as an Engine of Growth- Thomas Carré, Lennig Chalmel, Eloïse Villani, Jingxia Yang , Tresor Eco, August 30 , 2022

[3] Bottlenecks and monetary policy, Blog post by Philip R. Lane, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB - February 10, 2022

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Régis Genté

—

10 March 2026

Gender equality

Helen Levy

—

3 March 2026

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :