Democracy and citizenship

Laurent Mayet

-

Available versions :

EN

Laurent Mayet

Chair of the think-tank ‘Le Cercle Polaire’, former Special Representative for Polar issues at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Since the joint communication presented on 13 October 2021, ‘A stronger EU commitment to a peaceful, sustainable and prosperous Arctic region’, the Union's Arctic policy has not been updated or adapted whilst the geopolitical context has changed radically with Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, which has undermined the security and stability of the Euro-Atlantic area.

In this context several countries have revised their Arctic strategy: on 18 September 2024, the German government undertook a review of its Arctic policy to take into account the new geopolitical context that is undermining the integrity of the panarctic cooperation format known as “the Arctic Eight” (A8): Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States. In France, in March 2025, the Ministry of the Armed Forces presented a defence strategy for the Arctic, the main focus of which is the stability of the North Circumpolar Region. On 27 August, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs unveiled a new High North strategy entitled An Arctic Policy to Meet a New Reality, one of the priorities of which is ‘strengthening defence capabilities and cooperation with American and European Nordic allies’. Several European countries (Italy, Spain, etc.) have recently announced their intention to prepare an Arctic policy to integrate this strategic and security dimension into an area dedicated to ‘peace and cooperation’[1], since the end of the Cold War.

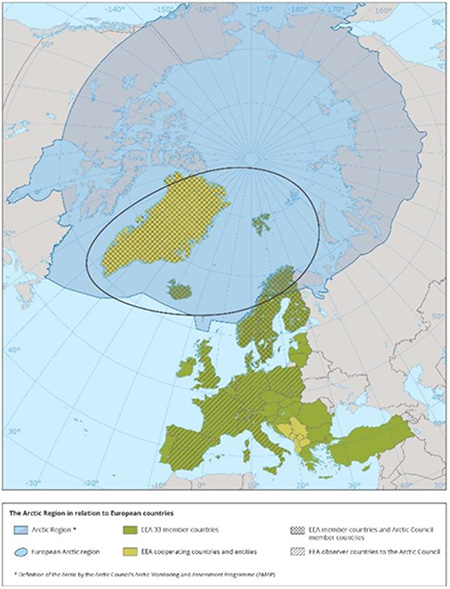

In contrast, the European Union's policy in the Arctic has been ‘heaving to’ for several years, to use a sailing term that refers to the safety manoeuvre of a sailing ship in heavy weather, which stops to assess the situation and wait for developments. With hopes of restoring international order or reconciliation between Ukraine and Russia looking slim, the question is how cooperation in the Arctic should be revived and what role the EU, “as a legislator in part of the European Arctic” (Fig.1), might play there.

In 2021, the European Union revised its Arctic policy that dated back to 2016, to include a strategic dimension in relation to the development of Russian military activities in the North Circumpolar Region, which seemed to ‘reflect both a strategic positioning on the world stage and domestic priorities, in particular the dual use of infrastructure’[2]. The 2021 communication marked a turning point, breaking with a founding principle of panarctic cooperation that emerged at the end of the Cold War, namely the exclusion of “matters related to military security”[3]. Since the establishment of the Arctic Council (AC) in 1996, this principle had been the guarantor of ‘Arctic exceptionalism’, a regime of cooperation in the high latitudes, sheltered from the tensions and divisions of geopolitics in the lower latitudes. This regime of peace and cooperation would be difficult to preserve in times of tension, a fortiori in times of geopolitical crisis, because the eight ‘Arctic States’[4] are actually subarctic or mid-latitude[5] ones, with territories located beyond the Arctic Circle (66° 33' N) without sui generis multilateral governance at the circumboreal regional level. The ‘peripheral’ model of the Arctic, with reference to the centre-periphery opposition used by geographers, provides a relevant framework to understand the political balance in the Arctic region, beyond the powerful mythology of the ‘North Pole, pole of peace and cooperation’.

‘Arctic exceptionalism’ undermined

This study extends and updates the analysis of the development of the Union's Arctic policy published by the Foundation in November 2021. The main challenge at the time was to ‘maintain peaceful constructive cooperation and dialogue in a changing geopolitical environment, so that the Arctic remains a safe and stable area (...) by stepping up regional cooperation and developing a strategic outlook on emerging security challenges’. The reference to a ‘changing geopolitical context’ mainly referred to the strengthening of military capabilities in the Russian Arctic and the increased assertion of Russian presence in Arctic waters and airspace.

The 2021 European Arctic Strategy was deployed on two fronts: on a diplomatic level, with the strengthening of ‘the European Union's participation in all Arctic Council working groups’; and in terms of military diplomacy, with the development of collaboration with partner countries and NATO on emerging security challenges. This second initiative was not meant to pose a threat to the balance within the Arctic Council, five of whose eight member States are NATO members (Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway and the United States) and two (Finland and Sweden) were NATO partners; Russia being the common strategic opponent that unites them. The question then arose as to whether regional cooperation in the Arctic, based on the sidelining of military security issues, could survive the parallel development of military diplomacy cooperation that was divisive for the Arctic Eight.

The answer to this exploratory question went far beyond the scope of the assumptions envisaged at the time, and panarctic cooperation fell apart with Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, as of 24 February 2022. A few days later, on 3 March, seven of the eight member states of the Arctic Council announced a boycott of meetings to be held in Russia under the Russian chairmanship that began on 21 March 2021. A new group had just emerged: the Arctic Seven (A7), whose unity was based on membership or partnership with NATO, in violation of the principle of excluding military security issues. For many months, the AC website displayed the following message: ‘Arctic Council meetings are adjourned until further notice.’ The decision to freeze activities rather than exclude a member from exercising the chairmanship (which was not provided for in the rules of procedure) was taken[6].

The Northern Dimension (ND), a common policy shared by the European Union, Russia, Norway and Iceland – with Belarus as an observer – promotes “good neighbourliness, balanced partnerships, shared responsibility and transparency”. The environmental partnership includes a nuclear safety component that aims to address the risks associated with large quantities of nuclear fuel and waste located in the Barents Sea, inherited from the Soviet era. On 8 March 2022, this cross-border cooperation programme suspended all activities involving Russia and Belarus in response to Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine.

The Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC) was established in 1993 on the ruins of the Cold War to ‘contribute to international peace and security’ (Kirkenes Declaration), with Finland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland and the European Commission as members. After thirty years of cooperation in the Arctic region, it suspended all cooperation activities with Russia in March 2022 and, on 18 February 2023, registered Russia's resignation. The Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs explained that: "Because of the Western States members of the BEAC, the Council's activities have been paralysed since March 2022. And since the Finnish Presidency of the BEAC did not confirm the transfer of the Presidency to Russia, scheduled for October 2023, in violation of the rule of rotation of the Presidency, Russia felt compelled to withdraw from the Barents Euro-Arctic Council," said Sergey Lavrov, Russian Foreign Minister.

In November 2024, Finland announced that it would leave the BEAC at the end of 2025 because this forum had lost its usefulness, preferring to strengthen its cooperation on the ‘Nordic region’ (Fig. 2) in particular with the Nordic Council of Ministers, an intergovernmental cooperation forum of five countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) and the Nordic Council, a forum for cooperation between parliamentarians from the Nordic countries, including Greenland, the Faroe Islands and Åland. A decision is expected in the coming months to determine the future of the BEAC, the only forum for cooperation on the Arctic in which the EU has member status.

The emergence of the Seven Western Arctic States Group (A7)

The diplomatic response of the European Union and the ‘Western Arctic States’, as the Russian authorities like to name them, to Russia's military invasion of Ukraine was swift, and forums for cooperation on the circumpolar Arctic (AC) and the Eastern Arctic[7] (ND) or the Barents Euro-Arctic region (BEAC) quickly froze their activities with Russia. In its 2021 communication, the European Union was careful to point out that ‘Arctic policy is based on the Union's participation in the work of the Arctic Council, the Barents Euro-Arctic Council and the Northern Dimension.’[8] It is therefore no exaggeration to say that the Union's cooperation policy in the Arctic is in a hove-to position due to the suspension of cooperation between the European Union, the non-member Nordic countries and, more broadly, the Western Arctic states (A7) with Russia.

“The decision by the Western Arctic States to temporarily freeze the activities of the Arctic Council did not prevent Russia from implementing its programme of activities, except for official meetings, during its two-year presidency,” explained Nikolay Korchunov, Senior Arctic Official and Ambassador for Arctic Cooperation at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. During its chairmanship from 20 May 2021 to 11 May 2023, “Russia organised 90 events (forums, conferences, festivals, sports competitions, etc.) on its territory in 24 cities covering the nine regions of the Russian Arctic,” according to Yury Trutnev, Deputy Prime Minister. The Russian presidency functioned in this manner as a ‘year of the (Russian) Arctic,’ and it was a blank period in terms of regional and international cooperation in the panarctic region.

Succeeding Russia as chair, Norway announced that it wanted to revive the Council's cooperation activities. Norwegian diplomacy towards Russia is multifaceted: ‘We will continue to cooperate in areas where Russia and Norway have common interests, [for example, fisheries management in the Barents Sea[9]] We will not explore new areas of cooperation with a regime that has launched brutal aggression against a neighbouring state. We have also frozen almost all government-to-government cooperation with the Kremlin”[10], explained Anniken Huitfeldt, Norway's Minister of Foreign Affairs (2021-2023), in November 2022.

Applied to the Arctic Council, this diplomatic algorithm would lead to a freeze on ministerial meetings while reviving, at the technical level, working groups bringing together experts and civil servants from States members and observers, with a preference for virtual videoconference for meetings. On the strength of this complex setting, Norway set about reviving the momentum for panarctic cooperation from May 2023 to May 2025. At the end of its two-year presidency, Espen Barth Eide, Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs since 2023, confessed that he had just spent ‘two difficult years’ due to ‘tensions within the Council related to Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine and Donald Trump's threats of US control over Greenland and Canada’[11]. Given the highly consensual cooperation themes (oceans, climate change, sustainable economic development, Arctic communities) that had been selected, the Norwegian Presidency's primary achievement was that, ‘unlike other Arctic cooperation bodies, no member left the Council or expressed a desire to freeze cooperation activities’[12].

Where does Norway's determination to preserve the integrity of the Arctic Eight format at all costs come from, given that it has been rendered ineffective by the diplomatic crisis linked to Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine? “The Arctic Council is central to cooperation in the Arctic and is irreplaceable; we must keep this forum alive at all costs”[13], said Maria Varteressian, State Secretary at the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in October 2024.

The Arctic Council, the main forum for panarctic cooperation

The Arctic Council is the only forum for panarctic cooperation that rallies all states with territories beyond the Arctic Circle, as well as representatives of the region's indigenous communities. It develops a comprehensive approach to the Arctic, transcending regionalism (North American, Russian, European, Euro-Arctic Barents Sea Region, Eastern Arctic). The Arctic Council's intergovernmental forum has thus created a unique space for international relations on the circumpolar Arctic, bringing together the countries directly concerned and a community of indirectly concerned actors (States, NGOs, interparliamentary organisations, etc.) with observer status. The Arctic Council, a centre of scientific expertise serving the governance challenges of human activities in the panarctic region is a fine idea which, after nearly thirty years of cooperation, has failed to produce concrete common rules and has never consolidated the international dimension of its scientific expertise due to the high level of politicisation of its activities. The case of the European Union is exemplary in this respect: a major funder of Arctic-related scientific research, the EU has continued to seek observer status since 2013, which is contested by Russia due to the sanctions imposed by the European Union in response to Russia's aggression against Ukraine.

The Arctic Council also acts as a ‘diplomatic preserve’ to prevent other forums from taking up Arctic issues and to contain the international community's interest in the emerging panarctic zone (increased accessibility of the Arctic Ocean and offshore natural resources, new shipping routes, etc.). By presenting a united front of states with territories located above the Arctic Circle, it reminds the world that the Arctic, the scene of a major environmental transition under pressure from climate change, is ‘a region that falls [mainly] under the sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction of the Arctic states.’[14]

For many years, the Arctic Council has sought to curb the enthusiasm of the international community: China claims the status of a ‘near-Arctic state’, the United Kingdom has proclaimed itself the ‘closest state to the Arctic’; requests for observer status are rising and, the European Union, comprising 27 states, which, depending on the area (environment, transport), may eventually share or even replace (conservation of marine biological resources) the representation of some European member states or observers of the AC, is still awaiting observer status.

This stance was manifested through a policy of diplomatic lockdown (freezing grants for new observer status, limiting the ‘primary role of observers’ to ‘observing the work’[15]), to the detriment of the international dimension of scientific expertise. At a time when the A8 format is faltering with the marginalisation of Russia, Norway has made no secret of its concern about the prospect of an Arctic Council that ‘would fragment into different organisations’[16], at a time when one of the Western Arctic states, the United States, is further undermining the cohesion of the A7 by denigrating multilateralism and questioning the reality of climate change, a central tenet of the Council's credo.

Arctic co-operation as a balancing lever between the Nordic powers and Russia

Since the end of the Cold War, international Arctic cooperation has always served as a bridge between Russia and the West. The Arctic Council brings together the former Cold War adversaries, determined to overcome the Arctic's strategic past and develop it into a ‘pole of peace and cooperation’. ‘High latitudes, low tensions,’ the Norwegian government has repeated tirelessly, emphasising again recently that ‘it is important for Norway to maintain an international forum for cooperation on the North.’ For Norway, as for the Nordic countries, the Arctic Council is the main forum for cooperation that brings together, with membership and at ministerial level, the Nordic countries, the United States and Russia. This multilateralism, balanced by the American presence, helps to offset the tense bilateral relations that the Nordic countries have with Russia.

This strategic function of balancing power, which has been the driving force behind the development of regional cooperation in the Arctic since the Rovaniemi Process and the Kirkenes Declaration in the early 1990s, with Finland and Norway sharing a border (land and/or sea) with Russia, can only have grown in importance at a time when Russia poses a threat to the security and stability of the Euro-Atlantic area, not only because of its war of aggression in Ukraine, but also because of the threat it poses to many countries in Northern Europe. On 8 May 2025, Norway launched its first national security strategy in response to the ‘most serious security situation the country has faced since the end of the Second World War’, linked to big threats from Russia, including the world's largest concentration of nuclear weapons, located not far from its borders.

This balancing act, which underpins Arctic multilateralism, has become somewhat less obvious with the major shift in transatlantic relations marked by the political will of the United States, NATO's main contributor, to scale back its commitment and investment in the security and stability of its European allies. However, Finland and Sweden's accession to NATO membership allows the Nordic allies and NATO to present a united front to Russia in the Far North.

With its scientific expertise, panarctic multilateralism and strategic role as a bridge between Russia and the West, the Arctic Council has played a decisive role since the end of the Cold War in establishing and developing a regional and international consultation mechanism on the future of this emerging area. But times have changed and the myth of the North Pole as a ‘pole of peace and cooperation’ is no longer valid. NATO’s assessment leaves little room for diplomatic accommodation and compromise: ‘In light of its hostile policies and actions, NATO can no longer consider Russia to be a partner. The Russian Federation is the most significant and direct threat to the Allies’ security.’[17] If the Arctic Council intends to continue its activities of scientific expertise, as a leading intergovernmental forum on Arctic issues, it will not be able to maintain a balancing act with Russia for long, as this requires military diplomacy. The strategy of preserving the AC’s integrity from the tensions of its political bodies, by neutralising them (freezing ministerial meetings, suspending intergovernmental relations with the Kremlin) promises to be a delicate one since the AC is subservient to those political bodies[18].

Towards an "A7+1" format

It may be necessary to accept the marginalisation of Russian power within the Council. Norway, like other Nordic States, will no longer be able to rely on the Council to foster technical cooperation and counterbalance its tense relations with its Russian neighbour. International cooperation on the Arctic can no longer serve as a bridge between Russia and the West. The Arctic Council must strive to revive cooperation with the western Arctic states and the international community, without Russia. Its statutes do not provide for a procedure for the exclusion (temporary or permanent) of a member, but they do include a provision that could be used to manage, temporarily or permanently, the crisis it is currently experiencing: "Six Arctic States shall constitute a quorum for a Ministerial meeting or a meeting of Senior Arctic Officials (SAO) (Article 3); if not all States can be represented at a ministerial (or SAO) meeting, subject to the quorum rule, a record of the decisions will be sent to the absent States for validation of the decisions within 45 days (30 days) of receipt of the notification". This approach would be more effective if it were presented by the Council as a crisis response, with the publication of an A7+1 format that names and shames one of its members, rather than continuing to hide behind the hackneyed myth of the North Pole as a ‘pole of peace and cooperation’. In doing so, the A7 risk Russia's withdrawal, but this is a risk worth taking if the deadlock is to be broken.

The future and balance of international cooperation in the Arctic, insofar as it involves relations between Russia and the West, therefore depend on a possible resolution to Russia's war against Ukraine but, more broadly, on Russia's foreign policy and action. This observation shows that Arctic exceptionalism will have been nothing more than a historical (post-Cold War) and circumstantial (period of peace) interlude, helping to legitimise the peripheral model of the Arctic, according to which the North circumpolar Region is, politically speaking, a community of mid-latitude or subarctic states with northern territories. Diplomatic priorities must be restored to their rightful place: beyond cooperation in the Arctic, disrupted by Russia's war against Ukraine, the European Union, a major player in the strategy of pressure exerted against Russia, is mobilising to try to restore comprehensive, lasting and just peace in Ukraine, and the respect for international law and the rule of law in Europe.

The EU can boast that it ‘has an important role to play in supporting successful Arctic cooperation and helping to meet the challenges now facing the region’. But the truth is that, in the turmoil that the Arctic Council has been facing since March 2022, the European Union, with its “permanent guest” status, has not carried much weight and is in no way involved, any more than the other observers, in discussions on the future of international relations in the circumpolar Arctic.

For several years now, the European External Action Service (EEAS) has reminded us that regional cooperation bodies in the Arctic, of which the EU is a member, have frozen their cooperation with Russia. This has slowed down or even paralysed regional cooperation in the Euro-Arctic Barents Sea region, the Baltic Sea region and, more broadly, in the Eastern Arctic. The EEAS explains that ‘the Union takes the view that cooperation on Arctic matters with like-minded interlocutors, in relevant bodies via suitable channels, should be carried forward’. This suggestion sounds like a call to break the deadlock and rebuild the Union's engagement in the Arctic, extending it to other channels or forums for cooperation that are less affected by geopolitics.

The idea that we need "more Arctic in the European Union and more European Union in the Arctic", in the words of Antti Rine, Prime Minister of Finland in 2019[19], does not shed much light on this prospect, especially since strengthening the Union's role in Arctic affairs depends on the willingness of the Arctic states, three of which are members of the Union, Finland, Sweden and Denmark and two others, Norway and Iceland, members of the European Economic Area. It is not certain that the EU has always enjoyed strong support from the Arctic states within the Council. Russia's veto on granting observer status to the European Union will have served as a smokescreen to hide a double game by some. Thus, ‘In terms of external relations, a lack of recognition at regional level contributes to minimising the Union's Arctic engagement.’[20]

However, the European Union has gained legitimacy as a stakeholder in the circumpolar Arctic alongside the five Arctic coastal states, with its exclusive competence in the protection of living marine resources earning it a place as a signatory, on 3 October 2018, to an agreement to prevent unregulated fishing in the high seas of the central Arctic Ocean. The idea of bringing ‘more Arctic into the European Union’, with six EU Member States having observer status in the AC, Finland's ambition to make Arctic policy a priority for the Union and Sweden's wish to see broad commitment from all EU Member States, have not been enough to overcome a problem with the image of European engagement in the Arctic within the European institutions, leading to the Arctic and related issues being seen as marginal topics.

The consolidation of European engagement in the Arctic seems to be a more operational orientation of its positioning, taking into account the internal and external dimensions of its policy and an Arctic geography in which these different dimensions can be deployed. The EU's diplomatic engagement in multilateral cooperation on the circumpolar Arctic, whose issues and challenges have global implications, involves developing a more focused and applied policy, deployed in a specific Arctic geographical area, namely the European Arctic, where the EU has legal competence or strategic capacity for action. This area corresponds to the internal zones of the Union and the zones of close cooperation (Norway and Iceland, members of the EEA) where it has legal competence to act, and Greenland as a partner of the Union with Overseas Countries and Territories status.

The European Union has a partnership with Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, within the framework of the Overseas Countries and Territories Agreement. With a view to refocusing the Union's Arctic policy on the European Arctic, European rapprochement and partnerships with Nordic cooperation frameworks should not be overlooked, as the European Arctic region corresponds, for the most part, to the northern part of the Nordic region (Fig. 2).

These two proposals were already included in the 2021 communication: ‘As a geopolitical power, the European Union has strategic and immediate interests in both the European Arctic and the wider Arctic region.’ However, it must be acknowledged that, in the current strategic context, these guidelines have taken on unprecedented relevance and resonate with the logic of refocusing regional and international cooperation in the Arctic around Western states, opening up opportunities for closer relations and collaboration between Arctic and non-Arctic European states[21], which the European Union will be able to take advantage of.

When asked why the European Union is slow to revise its Arctic policy, as Germany, France and Norway have recently done, to include a strategic and security dimension, the answer is that, on the one hand, the Union was quite clear-sighted in anticipating this strategic shift in its joint communication of October 2021 and, on the other hand, that unlike powers such as France, Norway and Germany, the Union does not have the capacity or armed forces of its own nor competences[22] to develop a European defence strategy in the Arctic.

The idea of a review of the EU's Arctic policy is up for discussion. The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, announced on 17 July 2025, during a visit to Iceland, that "with the retreat of the Arctic ice cap, new realities have emerged, in particular the strategic presence and economic activity of Russia and China. Europe must adapt to these new realities, which is why we will be reviewing our Arctic strategy to ensure that it responds effectively to these new challenges." The aim is to consolidate a Euro-Nordic dimension of the European Union's cooperation in the Arctic and, in particular, to strengthen its position in the European Arctic by developing partnerships with the appropriate Nordic forums.

Annex

Fig. 1 : European Arctic Region

The European Arctic refers to a heterogeneous group of territories in the Arctic region belonging to five northern states: Sweden, Denmark and Finland, which are members of the EU; two EEA member states (Norway and Iceland); and the autonomous territory of Greenland (part of Denmark, a member of the EU), which is a partner of the Union with OCT status. The area thus delimited (black line) should not be considered as a region with a clear geographical definition, and its outline should not be interpreted as having a well-defined legal value.

Source : European Environment Agency, 2017

Fig. 2 : Nordic Region

The Nordic region is generally defined as comprising the territories of five sovereign states: Norway, Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Iceland, as well as their autonomous territories: the Faroe Islands and Greenland (Denmark), and the Åland Islands (Finland). These states form a distinct region due to the strong historical ties that unite them and their tradition of intergovernmental cooperation across borders.

Source : nordic.info, Aarhus University

[1] Mikhail Gorbachev, Murmansk speech, 1987.

[2] JOIN(2021) 27 final, Introduction, p.3

[3] Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council, Ottawa, 1996

[4] "Arctic States" means "Member of the Arctic Council", as defined in the 2013 Rules of Procedure. This is a political definition, not a geographical one.

[5] "Treating the Arctic as a distinct region is not intuitively self-evident (...) the Arctic consists mainly of a juxtaposition of northern segments of national territories whose centres of gravity are concentrated, for the most part, much further south". “Arctic Human Development Report” 2004

[6] Arctic Council Rules of Procedure, 1998, revised in 2013.

[7] Geographically, the DS also includes the eastern end of the Western Arctic with Iceland.

[9] In October 2022, Norway and Russia signed an agreement on fishing quotas in the Barents Sea for 2023.

[10] Russia conference 2022, Oslo, 15 November 2022.

[11] Miranda Bryant, Norway hands over Arctic Council intact after “difficult” term as chair, Guardian, 12 May 2025.

[13] Arctic Circle Assembly, October 2024.

[14] Arctic Council Rules of Procedure, Annex 2, Article 6b, May 2013.

[16] For instance, two different international collaboration forms in the Arctic, one of which brings together Russia, China and some others countries.

[17] NATO, Relations with Russia, 9 August 2024

[18] Each Arctic State appoints an SAO, which is responsible for discussing and reviewing the reports submitted by the working groups (cf. CA Rules of Procedure, 2013).

[19] Arctic Circle Conference, Reykjavik, October 2019

[20] A. Raspotnik, The great illusion revisited : the future of the European Union’s Arctic Engagement, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2020.

[21] "Non-arctic state" is the name given by the Arctic Council to states with observer status.

[22] Defence remains essentially a national prerogative. However, Member States may decide to conduct joint military missions under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP).

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :