Enlargement and Borders

Elise Bernard

-

Available versions :

EN

Elise Bernard

Doctor of Law, Head of Studies at the Robert Schuman Foundation

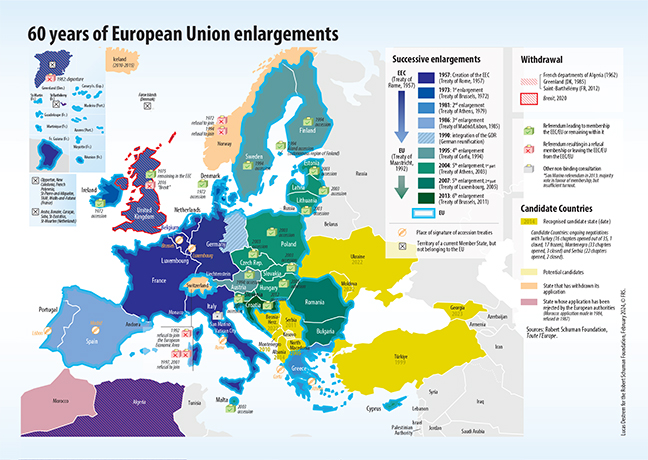

The accession of 10 new states to the European Union on 1 May 2004 is still, 20 years later, seen as a symbol of the peaceful unity of the continent. A schedule of 31 negotiating chapters — 80,000 pages of the Official Journal of the European Communities to be transposed, 470 legal texts to be incorporated into the national legal systems by the parliaments of the candidate countries, massive recruitment in the administrations and new calculations for the payment of financial aid — helped history speed up on its way. All this was underpinned by 826 twinning projects between towns and cities[1].

“Here are ten Member States, some of which did not even exist twelve years ago,” announced Jean-Claude Juncker in Paris on 26 February 2004. The decision to welcome ten countries at once was taken at the Copenhagen European Council on 12 and 13 December 2002, and with these negotiations were brought to a close. Almost ten years after the publication of the Copenhagen Criteria, the resolve to give expression to the enlargement of the European Union towards the East became a reality. On 16 April 2003, the representatives of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia signed the Treaty on the accession of ten new Member States to the European Union in Athens. On this occasion, Austrian Chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel declared, “For us Austrians, who grew up with a border secured by barbed wire, minefields and watchtowers, from an internal point of view the 21st century has in many ways only just begun. It's what we have dreamed of.” Dominique de Villepin, then Minister for Foreign Affairs, replied before the vote to transpose the Treaty of Athens[2] into French law some months later: “The European Union has set out the path that we are opening up to new partners: the path that has helped us emerge from war and centuries of division. The Founding Fathers - Konrad Adenauer, Alcide de Gasperi, Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet - invented this new route for the continent and breathed new life into the European idea”.

The magnitude of the symbol goes beyond the disagreements sparked by the declaration of the Vilnius Group and the rallying of Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic to the American interventionist campaign in Iraq. This attachment to the "American umbrella" in terms of the continent's defence, to the detriment of European ideals, dates back to this period. The Europe that was being built in 2004 ignored this point because, as commented by Bernard Guetta: “455 million Europeans, united in a single Union that relegates centuries of war, Nazism, Communism and the division of the continent into two hostile blocs to the rank of distant historical memories, soon to be as faded as those strange times when France, Germany and Italy were seeking unity. Never before has peace enjoyed triumph such as this.” In 2004, Europe was licking its wounds from the Cold War and idealising its future without taking much notice of the difficulties that lay ahead. 20 years on, it is time to take stock of the contributions made and the difficulties encountered by what is now known as the “Largest-Ever EU Enlargement”.

10 new States: a new demographic strength

The demographic analyses of the time highlighted the Union's new demographic strength, but also warned of its future weaknesses. With the accession of ten new members in May 2004, the European Union spread across almost 4 million km2 and 455 million inhabitants. This ranked it third in the world, behind China (1.3 billion) and India (1.1 billion), and well ahead of the United States (295 million) and Russia (142 million). In the 47 years between 1957 and 2004, Europe's population tripled, from 167 million to 455 million. The 10 new Member States had a combined population of 74 million, but in fact Europe increased its population by only 20%. This, the 5th enlargement was less substantial than the 1st in 1973, when 64 million people were added to the 192 million inhabitants of the six founding countries, resulting in an increase of one third ((64/192)×100% = 33.33%).

It was not the growth of the population that revolutionised the Union in 2004, but it did highlight the ever-decreasing demographic weight of the major member countries. While the FRG, France and Italy together accounted for, nearly 90 % of the population in 1957, on 1 May 2004, they accounted for only 44%. In addition, the 10 new members initially slowed down the demographic growth of the European Union, because they had a deficit in natural population growth, with more deaths than births, and their migratory balance was also negative. Improvements over the last 20 years do not indicate that this trend has been reversed: forecasts for 2050 anticipate a population at the same level, or even a reduction.

If a country like Ukraine were to join, the Union, which currently has 448 million inhabitants, would, according to projections, see its population increase by 36 million, and then would have 484 million inhabitants, a gain of 8%. The three main founding members (Germany 84 million, France 68 million and Italy 58 million), which currently account for 48% of the Union's total population, would see their share further reduced to 46%. This will have to be taken into account when the time comes for institutional reforms.

Europe’s population is ageing, much less so in France, but it particularly the case in Germany and especially in the ten States that joined the Union in 2004. An ageing Europe means loss of power and competitiveness; this should be the cause of concern.

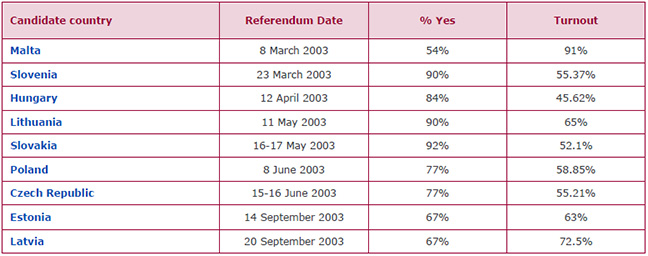

9 accession referendums: victory for participative democracy

Joining the European Union is the fruit of a long process but it was not necessarily longer because of the number of States being admitted in 2004. The Treaty of Athens, made possible by the agreement of the Commission and the European Parliament to the decision of the Copenhagen European Council, pursuant to article 49 of the TEU - identified the Member States and their date of entry into the Union. This treaty, in accordance with public international law, had to be ratified by all of the States involved, both old and new. This procedure was carried out by parliamentary means in the Member States, with few abstentions or votes against[3]. The latter authorised the accession of candidate countries "en bloc", as parties to a single treaty. In all the candidate countries except Cyprus, the ratification procedure was carried out by referendum.

Jean-Dominique Giuliani, L’élargissement de l’Europe, PUF, coll. Que sais-je ? 2004, p. 28

Two features differentiate these referendums. Those in Malta, Slovenia and Hungary were held before the signing of the Treaty of Athens because they were also intended to authorise the signing of the Treaty.

Malta was the first to organise its referendum regarding its entry into the European Union. Victory was far from certain, as the Labour Party campaigned against integration. It was at this time that the future President of the European Parliament Roberta Metsola, then a student, voted in support of Malta’s accession to the Union.

Slovenia followed, holding a referendum on both EU and NATO membership. Opponents were active during the campaign in terms of rejecting membership of the Atlantic Alliance; but membership of the Union was not a problem and the number of votes in favour bear witness to this. In Slovenia, Europe had been the focus of attention since the end of the 1980’s; Maja Bučar and Boštjan Udovič explain that the Communist Party was already calling for “Europe Now”. Despite the difficulties caused by the break-up of Yugoslavia, its economic performance and the general enthusiasm for accession meant that it was quickly described as the "best pupil" among the candidates.

In Hungary the campaign in support of the “yes” vote was launched with the President of the European Parliament, Pat Cox, in attendance, and the then Mayor of Budapest, Gabor Demszky, declared on the occasion of the commemoration of the revolt against the Habsburg Empire: “One hundred and fifty years ago, circumstances worked against the Hungarian revolution, but today Europe is with us, and it is up to us whether we want to take advantage of this historic opportunity. We are patriots when we remain loyal to our ancestors of 1848 and to our principles, when we say a clear 'yes' to Europe.”

All of this enthusiasm for European democracy through the referendums was encouraging, but it tended to mask the difficulties ahead. Indeed, of the 10 States ready to join the Union, as the passage to a new era, there was one that preferred the status quo. Indeed surprising as it might seem, 20 years ago, Recep Tayyip Erdogan supported the reunification of Cyprus, seen as a prerequisite for Türkiye’s accession to the European Union. Just days before the enlargement the Annan Plan was rejected during the referendum organised on 27 April 2004, with questions still pending some 20 years later: a puppet enemy in the north of the island and Türkiye’s accession to the Union more improbable than ever.

8 former Party-States: a fight against autocratic systems

In the decade leading up to the grand enlargement, efforts focused on the transition to a market economy. The undeniable mobilisation of the European Union, the EBRD and the EIB throughout the 1990s ensured that the transformation process was heading in the right direction. The data compiled by CEPII at the time lead to this conclusion: Western financial engagement - and that of the EU in particular - enabled the transition to a market economy using tools adapted to each post-communist national economy[4].

This transition enabled - albeit unevenly - integration into the single market in successive stages[5]. On the eve of accession, among the 8 countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia), economic growth rates averaged 3.8%, with forecasts of an increase thanks to the additional exports planned by the EBRD[6]. But the 1990’s were turbulent for these societies[7] and pre-existing inequalities were not resolved. Indeed, although the communist economic system had ended, talking about post-communism as far as the regimes were concerned posed a problem. Georges Mink and Jean-Charles Szurek wondered whether it was possible to imagine a clean break while Eastern European societies were still deeply imbued with the characteristics of the regime they had thrown out[8].

There is no doubt that the main objective of the representatives of the former autocracies of the "Eastern bloc", when the process of political and economic transformation began, was to create liberal and democratic institutions, committed to the separation of powers, the rule of law, free and fair elections and freedom (of association and expression). However, at the time some observers[9] regretted that the representatives of these States spent more time exalting democracy than establishing institutions to strengthen it. In other words, how could equality between citizens be assured in the event of abuse if they themselves had no idea of the usefulness of a judicial system[10]? And if they did try, were they not discouraged by the many obstacles caused by their lack of resources, not to mention corruption? Of course, the Council of Europe[11], then Venice Commission and the European Court of Human Rights were created to provide texts and a justice system that meet the standards of the European rule of law. However, these efforts only take effect over a long period of time.

The final aspect specific to these 8 Eastern European states was the fear of the tanks of the Warsaw Pact. In 2004, they were counting on NATO to ensure peace and security. Vaclav Havel, former Czech president, already supported an extension into Ukraine. Russia remained a threat. In 2005, seemingly prescient, he explained to Le Monde that "in the countries that have experienced Soviet domination, there is a real sensitivity to certain dangers that are not always perceptible to outsiders (...) Those who have had experience of totalitarian regimes, of the consequences of 'appeasement policies' and of 'turning a blind eye' should sound the alarm. (...) (For) all those who belonged to that empire (...) there is sound knowledge of the methods and also a greater resistance to manipulation". The European Union was thus strengthened by opponents of the USSR, experienced in the methods of dissuasion and propaganda that targeted frightened, docile populations. European figures such as Donald Tusk and Kaja Kallas have borne witness to this over the last two years: they have become key players on the international stage and in the European institutions.

7 reshaped institutions: maintaining decision-making procedures

When the Iron Curtain fell, the need for reconciliation seemed natural, but the same did not go for maintaining the European institutional balance. The institutions had to make room for the future Member States, and the technical, legal and political difficulties seemed to spoil any European summit involving the very idea of institutional reform. Voices were already being raised[12] — following the crucial events represented by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the disappearance of the USSR — that the European Union had not adapted to the new European geopolitical context, and this disorder seems to have prompted the emergence of a widespread climate of mistrust. However, this did not prevent the European institutions from adapting to circumstances.

The accession of 10 new Member States radically changed the way the Commission operated. The increase from 15 to 25 Member States, "with the prospect of further accessions in the near future, can only add to an institutional system that is already fairly complex and therefore opaque."[13] The largest Member States (United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, France and Spain) accepted that they could dispense with a commissioner and propose only one, as did the smallest Member States[14]. So in 2004, each Member State appointed its own Commissioner and the European Commission grew to 25 members[15]. 20 years later, the rule of "at least" one Commissioner per Member State has still not been scrapped, even though Article 4 of the Protocol on the institutions of the Treaty of Nice states that "when the Union consists of twenty-seven Member States, the number of Members of the Commission shall be less than the number of Member States".[16] Indeed, in 2013, the entry of the 28th Member State, Croatia, immediately led to the arrival of a 28th Commissioner, without this really causing a stir.

In practice, the increase in the number of Commissioners linked to the increase in the number of Member States has not caused any difficulties. The "college" meets every week, each item on the agenda is presented by the Commissioner responsible for the area concerned and the college then takes a collective decision. This can be explained by the fact that the number of items discussed by the college has decreased significantly since 2005[17]. Decisions are taken before the weekly meeting: with the enlargement, the meetings of the Heads of Cabinet have become the place to defuse conflicts. The Commission has adapted to enlargement. "The weekly meeting of the College is more a time for identifying agreements than for reaching them. It is also very rare for a vote to be taken.”[18]

With the Largest-Ever EU Enlargement, the Commission underwent a slight internal transformation, as did the European Council, the Council of Ministers and the Commission[19], the Court of Justice and the Court of Auditors. And to our knowledge they have not experienced any difficulties in bringing together 25 state representatives or judges.

In 2004, the number of members of the European Parliament increased from 626 to 732. The Member States did not lose any seats; new ones were added. The only significant change concerns its rules of procedure, and in particular the formation of political groups. The new wording of Article 29, which took effect on 1 July 2004, stipulates that "each political group shall consist of Members elected in at least one fifth of the Member States. The minimum number of Members required to form a political group shall be sixteen".

Twenty years after the Largest-Ever EU Enlargement, the most notable development has been the creation and establishment of EU executive agencies in the Member States: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE, Vilnius, Lithuania); European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex, Warsaw, Poland); European Labour Authority (ELA, Bratislava, Slovakia); European Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (eu-LISA, Tallinn, Estonia); Agency supporting the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC Support Office, Riga, Latvia); European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA, Valetta, Malta); European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA, Prague, Czech Republic); European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL, Budapest, Hungary); European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER, Ljubljana, Slovenia).

The 6th European elections in 2004: enthusiasm undermined by abstention

Following the 2004 European elections, the 732 MEPs were divided into seven political groups, with no major change in the balance of power that had existed until then:

• the Group of the European People's Party - European Democrats (EPP-ED), with 268 members;

• the Group of the Party of European Socialists (PSE) with 200 members;

• the Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), with 88 members;

• the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance (V/ALE), with 42 members;

• the Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL), with 41 members;

• the Independence/Democracy Group (IND/DEM), with 37 members;

• the Union for Europe of the Nations Group (UEN), with 27 members;

• 29 non-attached members.[20]

Françoise Grossetête was right: the elected representatives of the new Member States and their unfamiliarity with the practice of European democracy did not disrupt everything: "the defence of national interests has never been a recipe for success within the Parliament". The 20 years that have followed have shown that MEPs tend to embrace a process of "European socialisation"[21].

What does stand out are the abstention rates. There are several reasons for the lack of interest in this ballot.

The first finding is both surprising and worrying. Barely one in two voters turned out for this election, which was supposed to illustrate the victory of democracy. Turnout stood at 44.03%, 6 points lower than in 1999, but above all it was a mere 26.34% among the 10 new Member States. When the data per State are analysed, the situation is even more worrying except in the two Mediterranean islands of Cyprus (71.2%) and Malta (82%)[22]. In the 8 other states that emerged from the Communist autocracies, the public did not play the game. In Poland, Hungary and Slovenia, the ballot boxes were sparsely filled. Only Lithuania had a decent turnout, but this was due to the fact that the presidential election was being held at the same time. The new Member States were quick to adopt this habit: taking advantage of the European elections to demonstrate their disagreement with national policy. It was on this occasion that Europeans discovered a social-democratic party that had emerged from the Communist Party (and was therefore the only one of its kind for almost fifty years), the SMER led by Robert Fico as well as the provocative euroscepticism of Vaclav Klaus which, twenty years on, still seem to have a following.

Is it worth turning out to elect this Parliament? This reflects what has been dubbed the "democratic deficit". The European Union is a union of states, so only national representatives seem to count. Moreover, parliamentary control is weak: the European Parliament has no means of holding these institutions to account, and the national parliaments can only control their representatives in the Council. The European Parliament has no control over the institution as such. It exerts a certain amount of pressure on the Commission at the time of its appointment and can submit a motion of censure, but this does not seem to be enough to motivate people[23]. 20 years on, the problem applies in the exact same terms.

The 5th enlargement: the progression of a certain vision of inter-state relations

“...The accession of ten new States to the European Union (...) restores Europe and requires it to redefine itself. (...) It is not a simple addition, but a redefinition that awaits the continent. In this respect, in the history of European integration, perhaps only the accession of Great Britain and Ireland, bringing with them the Anglo-Saxon universe, provides an idea of the change in nature that is beginning today. And yet. For although the date of 1 May 2004 certainly does not mark the end of the unification project, it already heralds its future contours. The building site is not complete, but the shell is. Only one wing remains to be completed, that of Orthodox Europe, and a few holes to be filled.”[24] The area covered by the European Union has varied. The Community expanded towards the North in 1973, and was reduced in scope with Algeria's independence[25] and the withdrawal of Danish Greenland[26]. The 2nd and 3rd enlargements[27] led to an extension towards the South and the recognition of a successful democratic transition. The extension of the EEC towards the former GDR was not considered to be an enlargement because, unlike the previous ones and the one that followed that took in the former so-called Cold War “buffer” States”, it did not give rise to the so-called enlargement procedure. The 5th enlargement of 2004 therefore represented a synthesis: the Cold War was over and it was accepted that the 8 countries concerned had put an end to their autocratic regimes.

The four previous enlargements did not elicit as many comments, mixing fear and enthusiasm. The first was postponed because of strong opposition to the United Kingdom joining the European Communities[28], but contributions to peace and reconciliation in Ireland have made it a success in this sense[29]. The 2nd and 3rd could be seen as a reward for having toppled the dictatorships in Greece, Spain and Portugal[30]. The 4th in 1995 was like an announcement of the clearance of the land bordering the Iron Curtain. The benefits of enlargement for the new member states are easy to grasp: economic stability could not have been more welcome, especially after the difficult decade experienced by the former planned economies in the 1990s, and the effects of the isolation of the Mediterranean islands was to be reduced. As far as the Member States are concerned, their first fear was of social dumping with the so-called Polish plumber.

However, enlargement is first and foremost about its contribution to the Union as a whole. It has to be admitted that enlargement is the most effective tool in terms of foreign policy. Driving forces behind legislative reforms that encourage development and stability, it was argued that the logic of territorial linkage — with Franco-German reconciliation as a model — "deepens the European geopolitical project by giving it a broader and more solid territorial basis". This offers the European Union the prospect of becoming a recognised mediator and conflict manager on the international stage. In a way, this is what is happening 20 years later in Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia.

4 Central European States seeking their place

In 2024, everyone will be thinking about the unfortunate statements made by Robert Fico and Viktor Orban, or the Polish cases brought before the European Court of Justice and financial penalties relating to the non-respect of the Rule of Law. Central Europe is disturbing, and this can be explained by a delicate positioning for itself. In 1983, the Czech writer Milan Kundera made the following diagnosis: Central Europe is "culturally linked to the West, geographically to the Centre, politically to the East"[31].

The first country to stand out was the Czech Republic. In November 2009, after the failure of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe and the rescue at the last minute of the necessary institutional advances, the whole of Europe had its eyes on the Prague Constitutional Court: the future of the Lisbon Treaty now depended on its decision on compliance with the Czech constitutional order. On reading the ruling, it seemed highly favourable to Europe, a far cry from the interpretation given to the decisions taken by the Germans. The entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty was postponed, slowed down even, because the Czech President at the time, Vaclav Klaus, had positioned himself as a troublemaker. Likewise in 2010, Viktor Orban, a young democrat and virulent opponent of the USSR in the 1980s, distinguished himself as an obstacle to progress, with provocations which had varying degrees of success. Hungary on the international scene, of course, but are the Hungarians satisfied with this? This can be questioned. Robert Fico seems to be going down the same path in Slovakia.

Beyond its economic contributions, Central Europe's other strength: building bridges with the East. Nathalie from Kaniv[32] recalls that at the European Doctoral College in Strasbourg, "We were in contact with historians from the Central European Institute in Lublin, directed by Professor Jerzy Kloczowski. We were studying Russian and Ukrainian discourse at the beginning of the 20th century and the shared feeling, on 1 May 2004, further strengthened our deep conviction that we were all Europeans, even if Kyiv still felt a little apart. At the time, Central Europe was clearly a crossroads: the historical and cultural proximity between Poland and Lithuania was just waiting to be highlighted, and democratic aspirations were already paving the way for the Orange Revolution in December 2004".

The courage of the 3 Baltic states

Anyone familiar with the contemporary history of our continent will be thinking of this: the three former Soviet republics around the Baltic Sea are an inescapable point of reference. "Emancipatory models for other regions of the former Soviet Union, including Moldavia and Western Ukraine, countries also forcibly annexed by Stalin. A fine lesson from history: the Empire perished where it had unduly expanded; and three tiny states, like David facing Goliath, proved capable of destabilising an immense and powerful federation.”[33] How can one not be in admiration of the human chain that was formed on 23 August 1989, an impressive mobilisation on the part of the citizens against the established order, ahead of the blows of the chisel on the Berlin Wall on the following 9 November?

Having gained their independence in 1991, these new sovereign states still had a lot to do. Priority was given to security, as the former invader was still a source of concern. 20 years later, the Baltic states' prudence is an asset that the European Union can be proud of. The experience of the Soviet occupation, the geographical proximity, the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad between Lithuania and Poland, and the presence of numerous Russian-speaking minorities (30.3% in Estonia, 34% in Latvia, etc.)[34] might have led the representatives of these states to prefer neutrality. Despite a growing Russian threat and limited national military capabilities, the Baltic States have placed their bets on NATO.

This was reflected first and foremost in the cooperation they established with their neighbours and their rapid participation in collective security systems. "The Baltic authorities are banking heavily on their status as members of NATO, seeking to consolidate their countries' position within the organisation. This is demonstrated by the creation of the Centre of Excellence for Strategic Communication (STRATCOM COE), officially inaugurated in Riga in 2015. Its function is not only to counter some of Russia's information and communication operations, but also to deepen the Baltic countries' anchorage in the Euro-Atlantic community and to perpetuate NATO's presence in the region.”[35] explains Živilė Kalibataitė.

They were criticised for their Atlanticist leanings and abstention from the European elections in 2004, but this criticism was short-lived. Economically, one speaks of Tigers, Estonia has been a pioneer in cybersecurity and the digital economy since 2007[36], Lithuania was the first to — openly — challenge China and is hosting the Belarusian opponent Svetlana Tikhanovskaya. 20 years on, Estonian Prime Minister, Kaja Kallas, symbolises Baltic and European heroism and the President of the Republic of Lithuania, Gitanas Nauseda, can only welcome the statements by the President of the French Republic on the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

2 Mediterranean islands: opening up to the world

Malta and Cyprus not only share their island specificity: they joined the euro zone in 2008 and bear witness to their emergence from a degree of isolation. "Membership of the European Union is always seen as a great advantage, essential to overcome the disadvantages associated with our small size and to ward off the dangers posed by our vulnerable position on the international stage," explains Marina Demetriou Stavrou, Deputy Secretary General of the European Democratic Party. "I remember a feeling of hope and optimism that new avenues were opening up for our small island, mainly in the political sphere, but also in education, culture and trade.”

Herman Grech, a journalist who covered the negotiations for Malta's accession to the European Union, recalls: "On 1 May 2004, I joined tens of thousands of my compatriots for the celebrations in Valetta. I felt proud to see my country formally take part in the European family. Twenty years later, I believe that this accession is still the best political decision Malta ever made, which makes Eddie Fenech Adami our “Father of Europe”, not forgetting the dynamism of Roberta Metsola, President of the European Parliament.”

The benefits of enlargement are readily apparent. They have continued to grow, and their strategic Mediterranean location offers easy access to markets in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. "For the Maltese, the good and bad opinions on the Union are always based on the same arguments," emphasises Herman Grech, "The Union has helped us to open up to the world. Some of my compatriots are still wary of this idea, but it's an excellent thing: we can easily study and work in other countries, and we allow other nationalities to do the same. I'm delighted to see tens of thousands of EU nationals coming to work and live in Malta, as well as thousands of third-country nationals. Many use Malta as a springboard to benefit from the advantages of the European Union, but unfortunately there are also 'disadvantages'.”

Malta offers a particularly desirable way of life, with visa-free access to the rest of the European Union and the Schengen area for 90 out of 180 days. Maltese law allows investors to obtain a three-month resident permit — and this is particularly problematic at the moment — the issuing of 'golden passports'. Of course, this possibility has been suspended for the citizens of Russia and Belarus, following the invasion of Ukraine, but it was one of the subjects being investigated by Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was murdered in 2017. The question of the conformity of the practice of "golden passports" is currently under challenge before the European Court of Justice. The infringement procedure was also launched by the European Commission in 2020 against Cyprus but the latter finally brought this practice to an end.

The ex-Yugoslav: the discreet good pupil

It was this term — taken from a report published by the French Senates Financial Committee — that was used to describe Slovenia, the only State that emerged from the collapse of the Yugoslav Federation which joined the Union on 1 May 2004[37]. It met the criteria to join the eurozone and the Schengen area in 2007, and took over the presidency of the Council in the first half of 2008. Deemed to be discrete from the internecine wars that tore Yugoslavia apart, it announced in April 2024 that it was proud to have been a member of the Union for the last 20 years, planning many celebrations to be promoted by its government. According to Nina Gregori, Executive Director of the European Union Agency for Asylum and contributor to the “Schuman Report 2024”, "The Union has always been — and must always be — perceived as a haven of peace".

Slovenia also stands out for its leading figures. The philosopher Slavoj Zizek, in particular, who wrote in the Guardian calling on Europeans to take responsibility for the war in Ukraine: "We should stop being obsessed by the concept of the ‘red line’, this endless quest for the right balance between support for Ukraine and the desire to avoid all-out war. The ‘red line’ is not an objective reality: Putin is constantly drawing new ones, and we are contributing to it by reacting to Russia's actions. When we ask ourselves "by sharing information with Ukraine, did the United States cross a line?", we forget a fundamental fact: it was Russia itself that crossed the line, by attacking Ukraine. So instead of thinking of ourselves as a group that simply reacts to Putin as an impenetrable evil genius, we'd do better to think about what we - the "free West" - want in this matter?”.

Slovenia has also made a name for itself with its former Prime Minister Janez Jansa, close to Viktor Orban and an admirer of Donald Trump (whose wife is of Slovenian origin), nicknamed the “Marshal Tweeto”.

***

20 years after the "grand enlargement", we are delighted with the benefits both for the European Union and for the States concerned. We also realise that some of the fears of the old Member States were not justified and that they should perhaps have paid more attention to the new ones. In the large European family, as in most families, the members make the effort to meet to discuss the circumstances. They can be angry for a long time, some pushing others to compromise. This family reunion can only take place if all the members - and not just the States - are enthusiastic, the difficulties posed by the Agenda 2030 bear witness to this in particular.

The author would like to thank Stefanie Buzmaniuk and Peggy Corlin of the Robert Schuman Foundation, Maria-Christina Sotiropoulou of the Paris School of Economics and Edouard Gaudot of ESSEC, as well as Nathalie de Kaniv, Marina Demetriou and Herman Grech.

[1] Jean-Dominique Giuliani, L’élargissement de l’Europe, PUF, coll. Que sais-je?, 2004, pp. 3-27.

[2] Signed at the foot of the Acropolis in the presence of 41 heads of state, Ibid. p. 28.

[4] Slovenia, which is not included in this table, had been receiving support from 2000 on under the framework programme PHARE, financial support for agriculture and a number of reforms needed to modernise its civil service. It had already advanced well in the process compared with other countries. Gérard Wild, Economie de la transition : le dossier, Centre d'Etudes Prospectives et d'Informations internationales, N°08, October 2001, p.86.

[5] Olivier Audeoud, « L'acquis communautaire, du mythe à la pratique », Revue d'études comparatives Est-Ouest, vol. 33, 2002, n°3,.pp. 72-74.

[6] BERD, Transition Report, 2004, p. 26,

[7] By 1999, only Poland and Slovakia had returned to their 1989 production levels. Annual growth in the general price level reached 600% in some years in Central and Eastern Europe", explains Gérard Wild, Economie de la transition : le dossier, Centre d'Etudes Prospectives et d'Informations internationales, No. 08, October 2001, p. 86.

[8] La grande conversion le destin des communistes en Europe de l'Est, Seuil, 1999, 311 p.

[9] John Gray , “Post-totalitarianism, Civil Society and the Limits of the Western Model,” in: J. Gray, Post-Liberalism: Studies in Political Thought, London: Routledge, 1996.

[10] On the mistrust of institutions in post-communist societies, see the study by Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves, “Weak Civic Engagement? Post-Communist Participation and Democratic Consolidation”, Polish Sociological Review, 2008, p. 57-71

[11] The 8 states that joined the Council of Europe between 1990 and 1995.

[12] Jiří Musil, “Europe Between Integration and Disintegration”, Czech Sociological Review, 1994, p. 5-20

[13] Renaud Dehousse, La fin de l’Europe, Flammarion, 2005, p. 50.

[14] The quid pro quo for giving up the second Commissioner for the largest States was a new weighting of votes in the Council and a new distribution of seats in the European Parliament.

[15] In May 2004, the ten new Commissioners joined the college chaired by Romano Prodi. They included Sandra Kalniete, a Latvian figure of resistance to the Soviet Union.

[16] From 1 January 2005: "Members of the Commission shall be chosen on the basis of equal rotation, the arrangements for which shall be decided by the Council, acting unanimously. The Council — i.e. the Member States — has never succeeded in doing this.

[17] Giuseppe Ciavarini Azzi, « La Commission européenne à 25 : qu'est-ce qui a changé ? », in Renaud Dehousse, Florence Deloche-Gaudez et Olivier Duhamel, Élargissement. Comment l'Europe s'adapte?, Presses de Sciences Po, coll. Évaluer l’Europe, Paris, 2006, p. 56.

[18] Paul Magnette, Le régime politique de l’Union européenne, Les Presses de Sciences Po, Paris, 2006, p. 115.

[19] We can assume that this has encouraged greater consideration of the qualified majority vote with the provisions of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe and the Treaty of Lisbon.

[20] Éric Perraudeau, « Les élections européennes de 2004 », Pouvoirs, vol. 112, no. 1, 2005, pp. 167-179.

[21] This trend has already been described by Marc Abélès, La vie quotidienne au Parlement européen, Paris Hachette, 1992, 443 p.

[22] It is compulsory to vote in Cyprus, which is not the case in Malta.

[23] Armin von Bogdandy, “The Lisbon Treaty as a Response to Transformation’s Democratic Skepticism”, in Maduro MP & Wind M, eds. The Transformation of Europe: Twenty-Five Years On, Cambridge University Press; 2017, pp. 206-218.

[24] Eric Hoesli, « Salut Aigars, Aelita et les autres ! », Le Temps, 1st May 2004.

[25] Georges Valay, « La Communauté Economique Européenne et les pays du Maghreb », in Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, n°2, 1966. pp. 199-225.

[26] Yves Gounin, « Les dynamiques d'éclatements d'États dans l'Union européenne : casse-tête juridique, défi politique », Politique étrangère, no. 4, 2013, pp. 11-22.

[27] Guy Longueville, “L'entrée de l'Espagne et du Portugal dans la CEE : enjeux, perspectives et premiers bilans”, in Économie & Prévision, n°78, 1987-2. pp. 19-51.

[28] Robert Chaouad, « Le Royaume-Uni et l'Europe : in and out », Revue internationale et stratégique, vol. 91, no. 3, 2013, pp. 151-161.

[29] Harris Clodagh. “Anglo-Irish Elite Cooperation and the Peace Process: The Impact of the EEC/EU”, Irish Studies in International Affairs, vol. 12, 2001, pp. 203–214.

[30] Anne Dulphy, Victor Pereira et Matthieu Trouvé, « L’Europe du Sud (Espagne, Portugal, Grèce) : nouvelles approches historiographiques des dictatures et de la transition démocratique (1960-2000). Introduction », Histoire@Politique, vol. 29, no. 2, 2016, pp. 1-8.

[31] Milan Kundera, « Un Occident kidnappé ou la tragédie de l’Europe centrale », Le Débat, 1983, p. 13.

[32] Nathalie de Kaniv, author of « La ‘Jeune Europe’ au sein d’une grande Union », Revue Défense Nationale, vol. 830, no. 5, 2020, pp. 47-53.

[33] Jean-François Soulet, Histoire de l'Europe de l'Est. De la Seconde Guerre mondiale à nos jours, Armand Colin, 2011, p. 181-200.

[34] Grazina Miniotaite : « Les orientations atlantiques et européennes dans la politique étrangère et de sécurité des États baltes. Permanence, équilibre et stabilité », in C. Bayou, M. Chillaud, Les États baltes en transition : le retour à l’Europe, Peter Lang, 2012, p. 28

[35] Živilė Kalibataitė, « Le positionnement stratégique des pays baltes face à la Russie », Revue Défense Nationale, vol. 802, no. 7, 2017, pp. 147-152.

[36] Léa Ronzaud, « « E-Estonie » : le « nation-branding » numérique comme stratégie de rayonnement international », Hérodote, vol. 177-178, no. 2-3, 2020, pp. 267-280.

[37] Croatia followed in 2013, the last country to join as a result of the enlargement. The other former Yugoslav states (Serbia, Montenegro, Northern Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina) are candidate countries or (Kosovo) potential candidate countries.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :