Strategy, Security and Defence

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

-

Available versions :

EN

Nicolas-Jean Brehon

Honorary Advisor to the Senate, specialist in budgetary issues

This article follows on from an initial analysis of European support for the defence industry, published in February 2025 by the Foundation. The focus was on the European Defence Fund (EDF). Given the interest in this subject and the importance of military issues in the European debate, a regular update of this work is proposed whenever an event or publication seems to warrant it. This is currently the case. In May 2025, the Commission published a document on the allocation of appropriations from the European Defence Fund (EDF) in 2024. This is the fourth allocation from the fund, bringing the EDF's European aid to €4 billion since its creation in 2021.

The EDF could be considered the foundation for a future defence investment fund. However, this recent decision marks a major shift in both budgetary and political terms, raising some questions and making this prospect less certain.

I - Budgetary Aspects

1 - Brief overview of the EDF

The European Defence Fund (EDF), launched in 2021, introduced military spending into the European budget. Until then, military expenditure had been incidental or symbolic. This was only natural, as military matters fall within the remit of Member States. With €8 billion earmarked in the 2021-2027 budget, the EDF became the cornerstone of European defence policy. The fund finances research and development for trans-European industrial programmes. Subsidies are paid to companies and entities (such as laboratories) rather than to Member States.

After the turning point in 2021, speed was gathered in 2023-2024: the war in Ukraine changed Europe's neighbourhood and the perception of emergencies. The EDF was then increased by €1.5 billion and other budgetary support was made available (ammunition production, aid for joint acquisitions). This was also the moment when the idea of a massive European armament plan emerged. Initiatives multiplied and the figures exploded: €100 billion, €500 billion and €800 billion were announced. The way in which the European Union and its Member States would work together was still unclear, but the momentum was there.

The war in Ukraine has changed Europe and is changing its budget.

The next multiannual financial framework (2028-2034) should confirm this new reality: the Commission's first draft budget was presented on 16 July. Regardless of the amount ultimately agreed by Member States, as budgetary planning remains a political decision for the European Council, the EDF should form the basis for European intervention in the area of military capabilities.

Admittedly, the resources remain modest in view of the Member States' military expenditure and the financial challenges of European defence, but with the EDF, Europe has moved out of the experimental laboratory to develop procedures and commit expenditure: €4 billion over four years. The EDF has thus given the Union experience in military financing and can serve as a basis for European intervention in the field of capabilities for the coming years. This is why it is important to follow developments closely, especially when they lead to new matters of concern.

2 - 2024 EDF funding

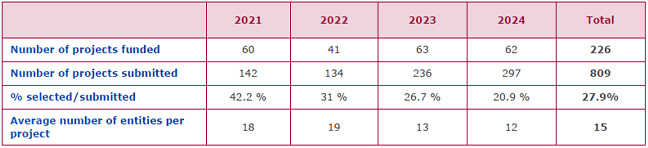

EDF grants average €1 billion per year. Although the Commission's document refers to an ‘investment close to 1 billion’, the 2024 allocation is slightly lower at €910 million[1]. This is a slight and unexpected shift in the current European context. But the 2025 programme is slightly higher. Nevertheless, the EDF is now a part of the European industrial landscape. The number of applications submitted has never been so high: 297 proposals. That is twice as many as in the first year in 2021. The selection process is therefore even more rigorous. Sixty-two programmes were selected, representing only one in five proposals.

Table 1:

EDF support for the defence industry (2021/2024)

Source : Author's calculations based on official figures published by the European Commission

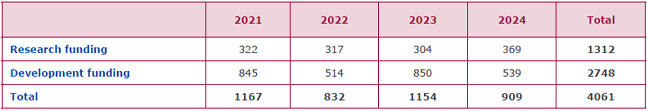

EDF grants are allocated in two areas: research and development. In 2024, the EDF witnessed a shift in the distribution of aid. The share allocated to research rose to 40% of the total, ten points higher than the average for the previous three years. Another notable change was the sharp decline in the share allocated to large projects. In 2024, the EDF financed only four major projects costing more than €50 million (total cost). This was much less than in the previous three years. Conversely, and as a result of the shift towards research, the share of small projects costing less than €5 million increased. In other words, we should not expect the EDF to finance the future strategic bomber or the development of a European Patriot missile defence system. The EDF remains a marginal tool in capability development. These trends are far from neutral in political terms.

Table 2:

EDF support for the defence industry (2021-2024)

Global financial data (million €)

Table 3:

EDF support for the defence industry (2021-2024)

Distribution of funding (numbers and %)

II - Political Aspects

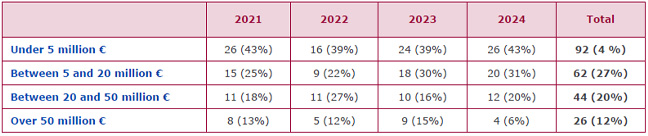

1 - Geographic distribution

The projects that receive funding are international consortiums. The previous article reported the reluctance of some manufacturers, who pointed to the complexity of the procedures, which is amplified by the need to include manufacturers or laboratories from several countries. ‘The more players there are, the more difficult it is,’ commented one regular participant, who expressed a preference for traditional industrial cooperation involving a small number of stakeholders. The 2024 allocation marked a shift in this regard: the number of participants fell and there were fewer international mega-programmes: eleven programmes with more than twenty participants in 2024, compared with eighteen in 2023.

In a programme, the key position is that of coordinator. The first article raised the issue of decision-making procedures. The Commission's decision is prepared with the assistance of a committee comprising representatives of the Member States and a committee of experts[2]. This procedure affects the distribution of funding. While some Member States would have preferred to base funding on the operational needs of their armed forces and the skills acquired over the years, it can be assumed that the Commission is using the EDF to create a new industrial landscape and favouring a regional approach to inclusion. It should ensure that funding is as balanced as possible so that no state feels left out and it has to strike a balance between efficiency and geographical balance. The EDF clearly favours the latter, suggesting that the Commission is implicitly opting for a kind of “budgetary juste retour”. This could lead to a certain degree of fragmentation[3].

The 2024 distribution even marked a shift in this regard. Three Member States maintained their leading position among coordinating countries: France, Spain and Greece. However, their position was no longer dominant. They accounted for only 40% of projects, compared with 50% in 2023 and 63% in the first year. The proliferation of small projects, particularly research projects, is a way of involving as many countries as possible.

Table 4:

EDF support 2021-2024

Data on major industrial coordination

2 - The emergence of new stakeholders

Coordination remains highly concentrated around the five countries mentioned above (France, Spain, Greece, Italy and Germany). However, 2024 saw the emergence of new companies from the Nordic countries, which until then had not really been involved in EDF procedures. This was the case for the Netherlands (four coordination projects for programmes worth €47 million), Estonia (three coordination projects for €117 million) and Denmark (three coordination projects for €11 million). This support goes beyond research alone. Three of the five largest programmes funded by the EDF in 2024 are coordinated by Estonian[4] and Finnish[5] companies. Special mention should be extended to Norway, a country that is not a member of the European Union but is associated with the EDF. Each year, at least one Norwegian company coordinates an EDF programme. Since 2021, Norway has coordinated six programmes worth €114 million.

Table 5:

EDF support 2021-2024

Data on the distribution of coordinations since 2021

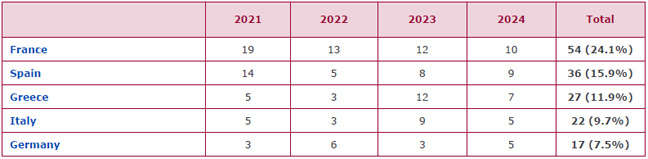

3 - The weakening of the French position

This development particularly affected France's position. Companies in this country are still very much involved in EDF-funded programmes (in two out of three cases) but are increasingly less involved in coordination: only ten coordination projects in 2024 (compared to nineteen in 2021), only one of which concerns a programme worth more than €50 million. In the latter case, the coordination is provided by Airbus Helicopters, which is classified by the EDF as a French company because its headquarters are in Marignane, but in fact it is a wholly European company.

This trend was also reflected in the figures involved. Although programmes coordinated by French companies represented a total of €1.6 billion over four financial years, the annual amounts for the programmes were almost halved in four years. On the other hand, programmes coordinated by French companies often remained significant (over the four financial years, there were eleven coordination projects for programmes worth more than €50 million). A similar trend was visible in the number of French companies involved in EDF programmes (whether as coordinators or simply as entities associated with programmes coordinated by others).

Table 6:

Support from the 2021/2024 EDF for projects coordinated by France and with French participation

Significance of projects coordinated by France

* This is not the amount received by the companies alone, but the amount allocated by the EDF to companies participating in the programmes.

** This is the total number of participations by French entities in EDF programmes, bearing in mind that the same entity or company may be involved in several programmes (e.g. Thalès).

4 - Growing questions about the German position and Franco-German cooperation

What if the EDF were also a sign, an illustration, of a worrying trend that is beginning to emerge?

Germany's position towards the EDF was discussed in the previous article. There is no doubt that ‘the German arms industry is experiencing unprecedented growth, consolidating its position among the major stakeholders in the global defence market’[6]. But there is also no doubt that Germany has very little interest in the EDF. The number of coordination projects undertaken by German companies is derisory given the country's industrial performance and capabilities: only five coordination projects, fewer than Spain or Greece.

However, there is a new and rather worrying phenomenon to note. Not only are German coordination projects very few in number, but they now exclude French companies almost entirely. These five projects, led by German companies, involve 49 enterprises, but only three of which are French. And these are modest ones at that: the Franco-German research institute in Saint-Louis, Aerix Systems, which specialises in multidirectional propulsion, and Laego, an emerging consulting firm specialising in defence, but so new that it does not yet have a website! German involvement in the EDF has always been modest, but at least the initial coordination efforts involved French entities (CNRS, CEA, Thales, etc.)[7]. This cooperation has ceased. On the German side, Franco-German industrial partnerships appear to be limited to the bare minimum.

This situation raises some doubts about Franco-German cooperation. Could the EDF be an outward sign of unease between the two countries? Or an additional indicator? The first steps in this bilateral cooperation seem more than hesitant. Franco-German cooperation on the future combat vehicle (MGCS), initiated in 2017, reached a milestone in April 2024 and is taking place in a context of competition with the Commission[8]. The new-generation fighter aircraft project (SCAF) seems to be experiencing the same setbacks. One after another, the partners (France, Germany, Belgium, Spain) have threatened to withdraw or remain ambiguous. Eight years after the programme was launched in 2017, everything is up for debate: governance, engine selection, etc. The EDF cannot be a foundation for industrial cooperation in armaments and defence without the cooperation of the major players. Unless, of course, they have already given up on this type of multilateral cooperation. European industrial cooperation obviously only makes sense if it is supported by commitments – at least tacit ones – to purchase European equipment and give preference to European products. What would be the point of European cooperation if arms purchases were made elsewhere, outside the Union?

III - Questions for the future

The proliferation of small programmes at the expense of large equipment programmes, the withdrawal of the French, the renunciation of the Germans, etc.: these are all signs that momentum seems to have stalled and that the EDF has not really made its mark on the defence industry landscape. In this context, every signal counts, especially budgetary signals. And right now, these are not good. The draft budget for 2026 presented by the Commission comes as a surprise. While the appropriations earmarked for defence (Title 13) remain unchanged thanks to the allocation of reserves (with nearly €2 billion in commitments), those allocated to the EDF (Chapters 13-02 and 13-03) are down 30% in commitments and 20% in payments. The EDF has dropped again below the billion mark to €980 million in commitments.

The Commission's proposal for the multiannual financial framework (MFF) for 2028–2034 is also rather ambiguous. The order of the headings, their wording, the way they are presented and prioritised are indicators that are just as significant as the amounts involved[9]. It was therefore entirely conceivable – and even expected in the current geopolitical context – that defence would become a separate heading in the next MFF. However, this is not the case.

Where are the defence appropriations? In heading 2, entitled “Competitiveness, prosperity and security”, within a “European Competitiveness Fund”, which is itself divided into five disparate elements (health, digital leadership, clean transition, etc.), including a sub-element entitled “Resilience and security, defence industry and space”. ‘The European Competitiveness Fund will provide significant support for investments in the areas of defence, security and space,’ says the Commission. Yet, despite all that is at stake, defence is only mentioned as a subset of a competitiveness heading. Is responding to the deterioration in the security environment through competitiveness really the right approach? Given the high expectations, is there not a risk of disappointment? Another surprising point is that there is no mention of the EDF anywhere. When questioned, the Commission services did not provide an explanation, leaving room for all kinds of speculation. Will the EDF be renewed and developed in the next MFF? Nothing is less certain.

The EDF is just one piece of the European defence puzzle. It has had the merit of formalising a kind of network of European defence companies. But there is much criticism, for example, of the dispersion of funds, the decision-making criteria, the feeling of disconnect from urgent issues, etc. The EDF could have been the foundation for greater European cooperation in the field of defence. Other programmes devoted to defence (the ASAP programme, ammunition procurement, and EDIRPA, support for joint armament procurement) are still to be assessed but appear less open to criticism. The European Defence Industrial Programme (EDIP), launched in 2024, is currently being finalised. There is undoubtedly energy and determination. But are they enough to meet the strategic challenges of the moment? Behind the rhetoric lies the reality of national interests and alliances. As always, the mode of governance and the amount of funding are the real determinants of public action. Regrettably European defence is clearly struggling to make its mark beyond rhetoric.

[1] However, this is only an initial communication and the final decision, published in the Official Journal a few months later, can differ significantly. See, for example, the Commission Decision of 13 November 2024.

[2] Article 26 & 34 of the EDF regulation

[3] For example, the 2024 allocation assigns responsibility for three coordination tasks to Cyprus.

[4] CITADEL range cyber defence programme (€60 million) and iMUGs 2 automated weapons programme (€54.9 million)

[5] AI Wasp programme of artificial intelligence applied to electronic warfare (€52.4 million)

[6] Jean-Baptiste Giraud, Armées, 3 July 2025

[7] Agami Eurigami Programme funded by the EDF in 2021

[8] Le très politique char de combat franco-allemand, Slate, 26 May 2024

[9] The approach to agriculture in the various MFFs is particularly instructive. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was once the first heading in the early MFFs, reflecting its budgetary weight. Agriculture has gone from being the first heading to an implicit subset of the second heading, to the point where the very word “agriculture” has disappeared from the 2014-2020 MFF in favour of “sustainable growth - natural resources”. This shift goes beyond the budgetary framework alone and is clearly a political indicator.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Régis Genté

—

10 March 2026

Gender equality

Helen Levy

—

3 March 2026

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :