Economic and Monetary Union

Patrice Cardot

-

Available versions :

EN

Patrice Cardot

Retired senior government official responsible for European affairs

Part Two

The first part of this study made a clear diagnosis: central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are redefining geopolitical balances, and Europe, with its digital euro project, is at a historic crossroads. Between China's speed, the hegemony of the dollar and the agility of private stablecoins, the European Union must move from principles to action.

The second part focuses on the following three questions:

- What are the institutional and geopolitical obstacles hindering the roll-out of the digital euro?

- What concrete scenarios are emerging for 2030, and how can they be anticipated?

- What operational roadmap is needed to transform the digital euro into a lever of sovereignty?

The issue is no longer whether the digital euro is necessary, but how to deploy it so that it becomes a tool of power and not just a technological gadget.

I. Institutional and geopolitical obstacles – Why is Europe procrastinating?

A. Internal divisions: when the European Union undermines itself

1. The North-South clash over economic governance: an irreconcilable conflict of visions?

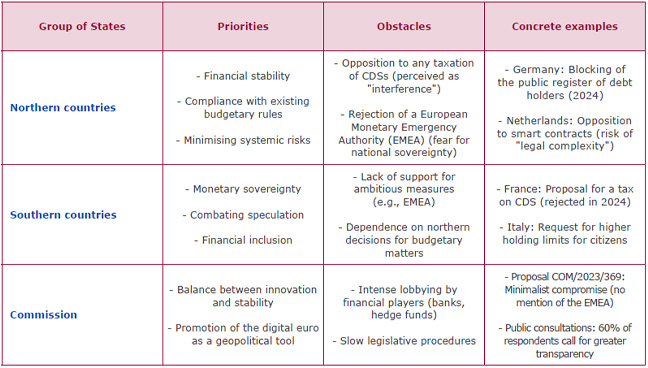

Since 2023, negotiations on the digital euro have revealed a deep divide between Member States, pitting two radically different conceptions of monetary sovereignty against each other. On the one hand, northern countries (Germany, the Netherlands, Finland) advocate a minimalist approach, focused on financial stability and compliance with existing budgetary rules. On the other, the southern countries (France, Italy, Spain) are calling for an ambitious tool that incorporates mechanisms for resilience, transparency and combating speculation.

The table below illustrates these differences: the northern countries, committed to fiscal orthodoxy, are blocking the most innovative measures (e.g. EMEA, tax on CDS (credit default swaps)), while southern countries, faced with more pressing social and economic challenges (unemployment, public debt), are pushing for more ambitious tools. Caught between these two fires, the Commission is proposing minimalist compromises, which risk rendering the digital euro ineffective in the face of geopolitical challenges.

Divergent positions within the Council (2025)

Source : Minutes of Ecofin Council meetings (2024–2025), COM/2023/369, Eurobarometer survey (2025).

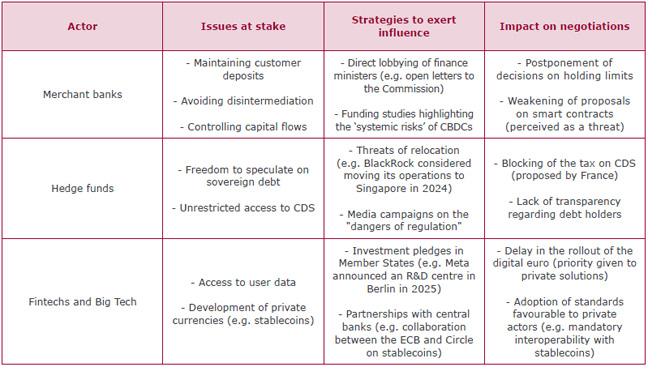

2. Opposition from financial lobbies: when private interests dictate monetary policy

The influence of financial players on European negotiations is a key factor in the stalling of the project. Three main interest groups exert constant pressure on decision-makers. The table below shows how private interests shape public policy. Merchant banks, for example, fear a flight of deposits to the digital euro (estimated at 15-20% by the ECB), which would reduce their ability to grant loans. Hedge funds speculate heavily on European sovereign debt via CDSs, with estimated gains of 15-20% on French ATBs in 2024[1]. Their opposition to any regulation (e.g. a 0.1% tax on CDS) has led to a status quo that costs European taxpayers €80 billion a year.

Main lobbies and their strategies for exerting influence (2023-2025)

Source : European Commission transparency reports (2024), ECB studies on disintermediation (2023), Financial Times articles on financial lobbying (2025)

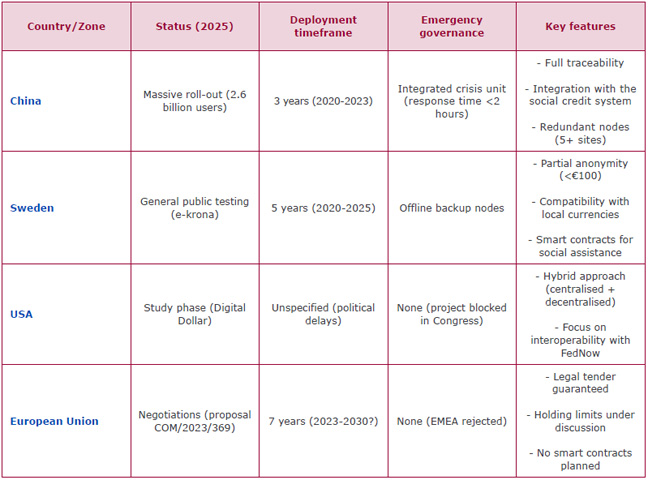

3. Technological and regulatory setbacks: a race against time

While China has rolled out its digital yuan in three years (2020-2023), Europe is falling behind. The table below compares the timelines and progress of the main players. It highlights the growing gap between the European Union and its competitors. China has not only rolled out its CBDC in record time, but has also incorporated resilience mechanisms (redundant nodes, crisis unit) that are absent from the European project. Sweden, although smaller, has innovated with solutions tailored to its citizens (partial anonymity, smart contracts). The European Union remains bogged down in political debates, with no emergency governance or advanced features. The result: an increased risk of marginalisation in the face of the digital yuan and private stablecoins.

International comparison of CBDC deployments (2025)

Source : BIS Reports (2025), Studies by the Bank of Sweden (2024), COM/2023/369.

B. External pressures: caught between China and the USA – the rock and a hard place

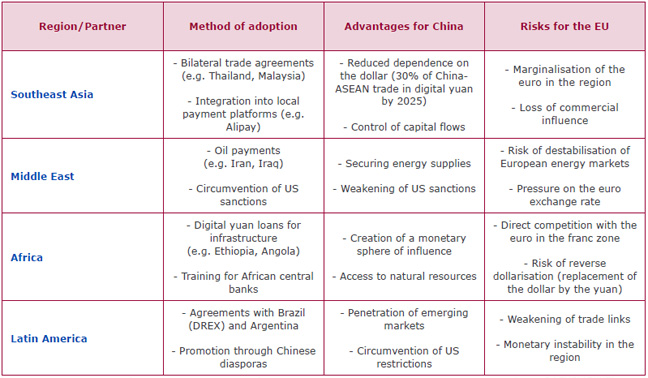

1. The threat of the digital yuan: A geo-economic containment strategy

Since 2020, China has been using its digital yuan as a tool for its soft power, specifically targeting developing countries and economies under sanctions. To illustrate this strategy, the table below reveals China's systematic approach to expanding its monetary influence by targeting regions where the European Union and the United States are vulnerable. In Africa, for example, the digital yuan is presented as an ‘unconditional’ alternative to IMF loans, appealing to countries such as Ethiopia and Angola. For the European Union, the risk is twofold: loss of market share (Africa accounts for 10% of European exports) and weakening of the euro as a reserve currency. Without a coordinated European response, the digital yuan could become the dominant currency in South-South trade by 2030.

Expansion of the digital yuan (2020–2025) – Targets and methods

Source : IMF reports on CBDCs (2024), World Bank studies on trade flows (2025), articles in the South China Morning Post (2023–2025).

2. American ambiguity: between technological delay and geopolitical pressure

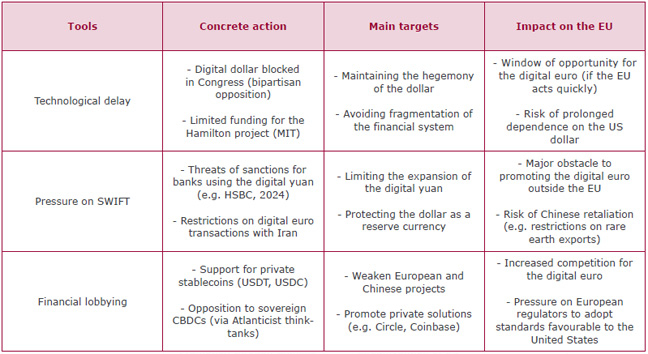

The United States is adopting a dual strategy: on the one hand, it is slowing down the development of its digital dollar to avoid undermining the current system; on the other hand, it is using its power over financial infrastructures (SWIFT, Fedwire) to limit the expansion of competing CBDCs. The United States is playing a double game: it is delaying its own CBDC to avoid weakening the dollar, while sabotaging competing projects (digital yuan, digital euro) via pressure on SWIFT and support for private stablecoins. This creates a dilemma for the European Union: either it accelerates the rollout of the digital euro to take advantage of the window of opportunity created by American inaction, or it submits to the rules of the game imposed by Washington and Beijing.

US strategy towards CBDC (2023-2025)

Source : US Congress reports on CBDCs (2024), Fed studies on the digital dollar (2023), Wall Street Journal articles (2025).

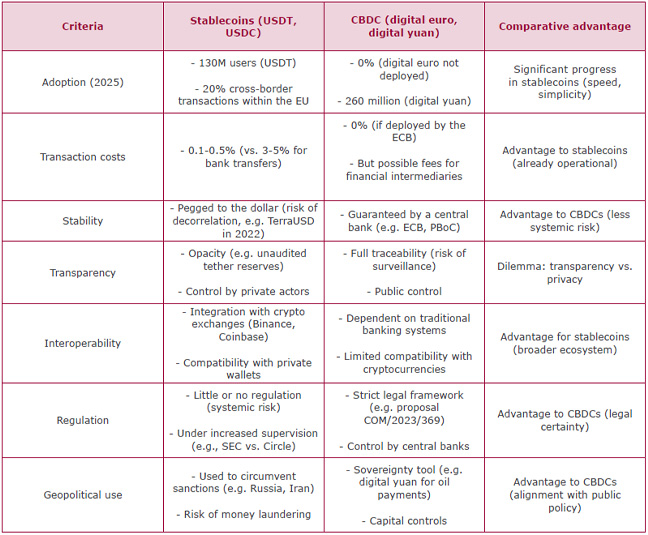

3. Competition from private stablecoins: an existential threat to the digital euro?

Stablecoins (USDT, USDC) and private cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin, Ethereum) are capturing a growing share of the payments market, particularly in emerging economies. The table below shows that stablecoins have a considerable lead in terms of adoption and ease of use, but suffer from systemic risks (opacity, volatility). CBDCs, on the other hand, offer institutional stability, but their deployment is slow and complex. For the digital euro, the challenge is twofold: to catch up in terms of adoption (via innovative features such as smart contracts), and to regulate stablecoins to prevent them from permanently capturing the market (e.g. 100% reserve requirement, forced interoperability with the digital euro). The table compares their adoption with sovereign CBDCs.

Comparison between private stablecoins and sovereign CBDCs (2025)

Source : BIS reports on stablecoins (2025), Chainalysis studies on crypto flows (2024), Digital euro proposal

II. 2030 scenarios – four possible futures for the digital euro

A. A systemic and sourced approach

To anticipate the possible futures of the digital euro, we draw on forward-looking studies such as those by the ECB: Digital Euro: Scenarios and Macro-Financial Implications; the IMF: The Geopolitics of CBDCs; and the European Commission: Impact Assessment on the Digital Euro.

The variables include the speed of deployment (2027 vs. 2030), the level of international cooperation (European Union-China-United States), and the regulation of private actors (stablecoins, cryptocurrencies).

The key players are institutional (ECB, European Parliament, Council), economic (commercial banks, fintechs, hedge funds) or geopolitical: China, United States, emerging countries.

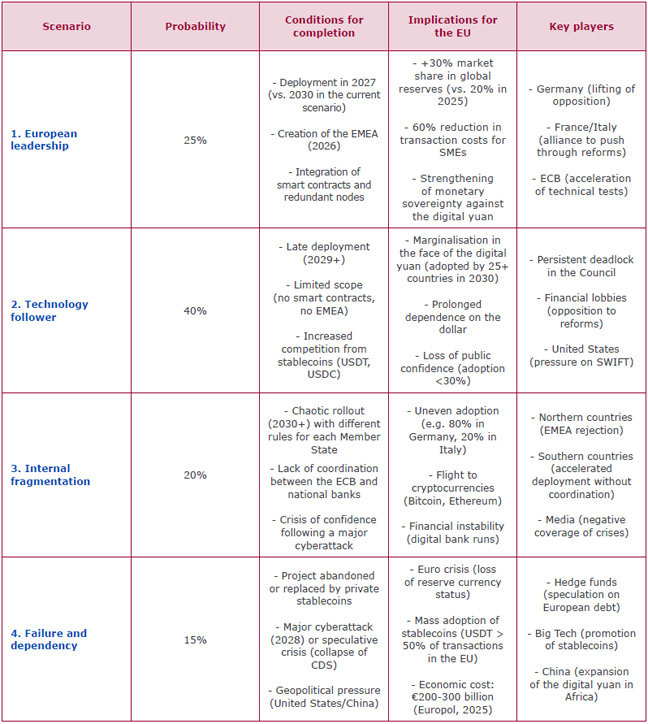

B. Four scenarios for 2030: between leadership and marginalisation

The actors which have been identified demonstrate that success will depend above all on the European Union's ability to overcome its internal divisions (North vs. South) and resist external pressures (United States, China).

Scenario 1 (European leadership) is the only one that allows the European Union to strengthen its monetary sovereignty, but it requires strong political will (creation of the EMU, accelerated deployment). It is only possible if the Union accelerates its reforms (EMEA, smart contracts, redundant nodes, post-quantum encryption guaranteeing transaction security) and resists American pressure. The digital euro would then capture 30% of global reserves (compared to 20% in 2025), thanks to its widespread adoption in trade with Africa and its integration into climate objectives. Thanks to the EMEA and redundant nodes, Europe would then be able to withstand a major cyberattack (similar to the one that paralysed the ECB in scenario 4), with 99.9% of transactions maintained and a response time reduced to less than two hours.

Scenario 2 (Technology Follower) is the most likely (40%) according to current projections, as it reflects the European Union's current inertia (political deadlock, financial lobbying). It would be the case if the European Union maintained its slow and conservative pace of deployment, without daring to undertake the necessary structural reforms: no smart contracts, no Authority (EMEA), and strict holding limits imposed by northern countries. Financial lobbies (commercial banks, hedge funds) and American pressure (via SWIFT and stablecoins) would then have succeeded in neutralising the most ambitious measures. The digital yuan, already adopted by more than 25 countries (particularly in Africa and South-East Asia), would then dominate South-South trade, while the dollar would remain the undisputed reserve currency.

Scenario 3 (internal fragmentation) would occur if the European Union failed to harmonise its rules and allowed each Member State to deploy its own version of the digital euro, without central coordination. The credibility of the digital euro would erode, paving the way for increased polarisation between Member States and a loss of influence vis-à-vis the digital yuan and the dollar.

Scenario 4 (Failure) would occur if the European Union were to abandon the digital euro project altogether or deploy it in such a watered-down version that it would be rendered obsolete even before its launch. Possible causes include a major cyberattack paralysing the ECB's infrastructure, a speculative crisis triggered by the collapse of credit default swaps (CDS) on sovereign debt, or joint geopolitical pressure from the United States and China to stifle the project. Such a scenario would have catastrophic consequences, with an estimated cost of €200-300 billion (payment paralysis, loss of confidence).

Prospective scenarios for the digital euro (2030)

Source : ECB scenarios (2024), IMF studies on monetary fragmentation (2025), Europol reports on cyber risks (2025).

III. Roadmap for 2026–2030 – Ten priority initiatives

A. Strengthening resilience and cybersecurity: a shield against crises

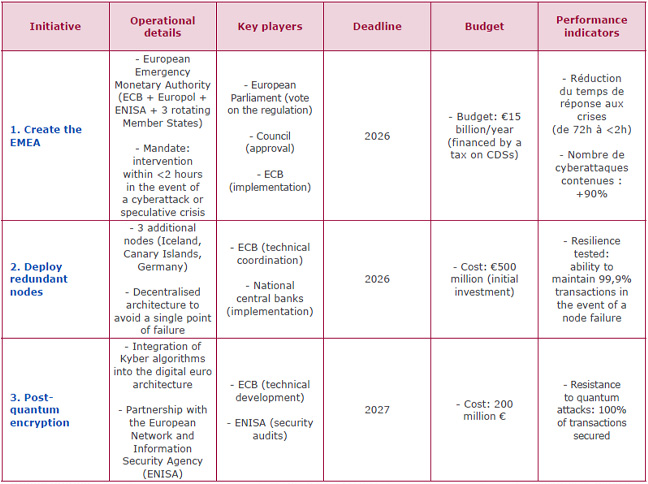

This action plan aims to strengthen the resilience of the digital euro against cyber threats (estimated to cost €10 billion per year according to Europol) and speculative crises. The EMEA is the key component: without it, there could be a 48-hour paralysis of payments following a cyberattack, costing 0.5% of European GDP per day (ECB, 2023). Redundant nodes and post-quantum encryption serve as technical safeguards to prevent a worst-case scenario.

Resilience Action Plan (2026-2027)

Source : Europol report on cyber threats (2025), ECB study on the resilience of CBDCs (2024).

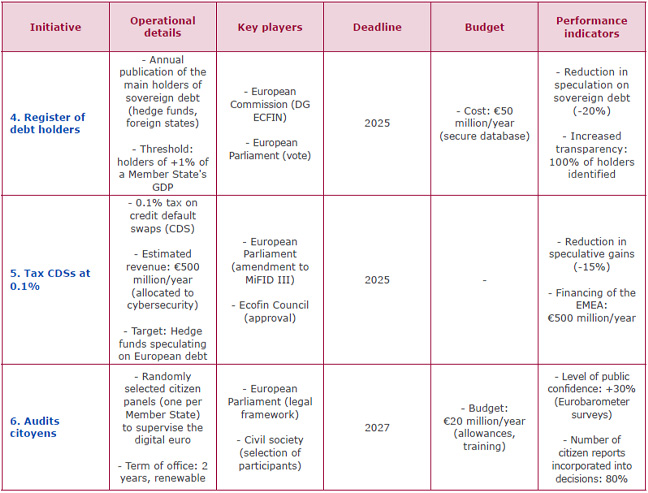

B. Ensuring transparency and democratic legitimacy

These measures aim to restore confidence in the digital euro, which has been eroded by financial scandals (e.g. speculation on sovereign debt) and a lack of transparency. The debt holder register would limit speculation (cost: €80 billion/year for the EU), while the CDS tax would generate revenue to finance resilience. Citizen audits, inspired by the Icelandic model, are a democratic innovation to involve citizens in monetary governance.

Measures for transparency and inclusion (2025-2027)

Source : France's proposal on the CDS tax (2024), Transparency International study on debt holders (2025).

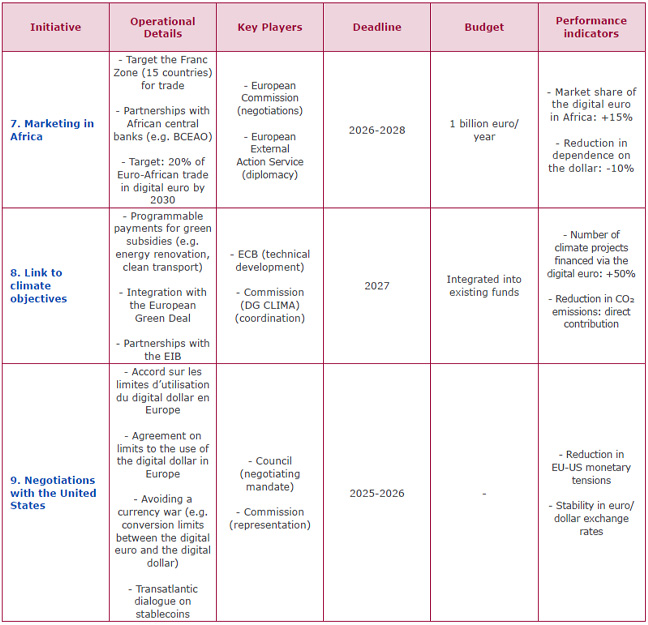

C. Turning the digital euro into a geopolitical lever

This geopolitical strategy aims to position the digital euro as a tool of power, targeting three possible levers: Africa, a key market where the digital yuan is rapidly gaining ground (e.g. Ethiopia, Angola); the ecological transition, a potentially strong argument for differentiating the digital euro from other CBDCs; and dialogue with the United States to avoid a currency war that would weaken both sides.

Geopolitical strategy for the digital euro (2026–2030)

Source : Stratégie de la Commission pour l’Afrique (2025), Rapports de la BEI sur le financement climatique (2024).

D. Regulating private players: avoiding monetary colonisation

This regulatory framework is crucial to prevent private stablecoins (USDT, USDC) from marginalising the digital euro. 100% reserves and mandatory interoperability are measures inspired by the IMF's recommendations (2024) to limit systemic risks. Without this regulation, stablecoins could capture up to 50% of cross-border transactions in the European Union by 2030 (ECB study, 2025).

Regulatory framework for stablecoins and cryptocurrencies (2025–2026)

Source : MiCA Regulation Proposal (2024), IMF Study on Stablecoins (2025).

***

Europe has everything it needs to make the digital euro a success – but also everything it needs for it to fail. Three priorities are essential for 2026: first, create the EMEA, because without emergency governance, the digital euro would be vulnerable to cyberattacks (cost: 0.5% of GDP/day) and speculative crises (e.g. CDS collapse); then, deploy redundant nodes to prevent system paralysis in the event of a failure (e.g. Iceland, Canary Islands, Germany) with an initial budget of €500 million; Finally, regulate stablecoins (revision of the MiCA regulation), because without a strict framework (100% reserves, interoperability), private players (USDT, USDC) will marginalise the digital euro.

The time for half-measures is over. China has already deployed its digital yuan. The United States is preparing its response. On 30 October, Europe launched the next stage of the digital euro project to make it a tool of power. If the co-legislators adopt the regulation by 2026, the digital euro could be issued in 2029. The die is cast.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :