Africa and the Middle East

Louis Caudron

-

Available versions :

EN

Louis Caudron

Former deputy director at the French Ministry of Cooperation

Europe, the world champion in public development aid

On 18 December 2020, the European Commission welcomed the political agreement reached between the European Parliament and the Member States allocating €79.5 billion to a new Neighbourhood, Development Cooperation and International Cooperation Instrument (NDCI) for the period 2021-2027.

Since its creation, the European Union has been a major player in public aid granted by rich countries to developing countries. The European Development Fund (EDF) was launched by the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and for decades provided aid to the former colonies in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific (ACP). The eleventh EDF, covering the period 2014-2020 with a budget of €30.5 billion, will be replaced by the NDICI (Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument).

The Union and its Member States are the world's largest donor of official development assistance. Their contribution of €74.4 billion in 2018 represents more than half of the OECD countries' Official Development Assistance ($150 billion in 2018).

Long-standing international commitment

For several decades, OECD member States have been committed to devoting at least 0.7% of their Gross National Income (GNI) in aid to developing countries. However this commitment, confirmed at the Monterey Conference in 2002, is respected by only a few countries: the Scandinavian countries, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom. Germany is currently at 0.61%, France is committed to reaching 0.55% in 2022 and the United States has reached 0.17%. The average for OECD countries is 0.31%.

In the 1960s, imbued with the memory of the Marshall Plan of 1947, European countries considered that it was in their best interest for the recipient countries to develop and thus become more interesting economic partners. Added to this, driven by the Scandinavian countries, there was a moral concern: the rich countries of the North had a duty to help the poor countries of the South.

A way to curb immigration?

Starting in the 2000s, many policymakers saw official development assistance as a way to curb immigration, mainly of African origin. Africa has not begun its demographic transition and the birth rate remains very high. According to UN projections, Africa's population has grown from 283 billion in 1960 to 1.341 million in 2020 and will reach 2.489 billion by 2050.

For 2050, these forecasts are reliable because most of the girls who will have children have already been born or will be born in the next ten years. However, no African country has embarked on a real birth control policy. Yet, for those who know the realities of Africa, such forecasts seem unrealistic.

We cannot see how Niger, a country largely comprising desert, will feed 66 million people in 2050, nor what it could sell to buy its food. Nigeria, with 206 million inhabitants in 2020, is expected to be the third most populous country in the world in 2050 with 401 million inhabitants. How will it manage a population density of 400 inhabitants per km2? Should we not be anticipating a wave of emigration by Nigerian farmers and herders to less densely populated neighbouring countries, with the high risk of conflict that this implies?

In recent years, several African countries have experienced significant annual growth rates of 4 to 6%. However, since the population is growing at 2 to 3 percent per year, economic growth of more than 6 percent per year would be required for many years to significantly increase GDP per capita. Major changes in African policies are needed to achieve this.

For some Africans, the "demographic dividend" - that is, the benefit of a growing population with many young people in the workforce and few elderly dependents - will facilitate Africa's development. This overlooks the fact that in Africa, many of the young people entering the market are poorly educated and find few productive jobs.

How many Africans will migrate to other continents if their basic needs are not met? Aging Europe, which is expected to shrink from 748 million inhabitants in 2020 to 710 million by 2050, is the closest continent, and can expect strong migration pressure from Africa.

The development aid policy has not helped Africa emerge from under-development

Often presented as a generous policy towards developing countries, official development assistance has not demonstrated its effectiveness. For Africa, the results are not good. As a priority continent in terms of official development assistance, for several decades it has received about $30 billion annually, but despite this massive aid, Africa remains the continent that has developed the least.

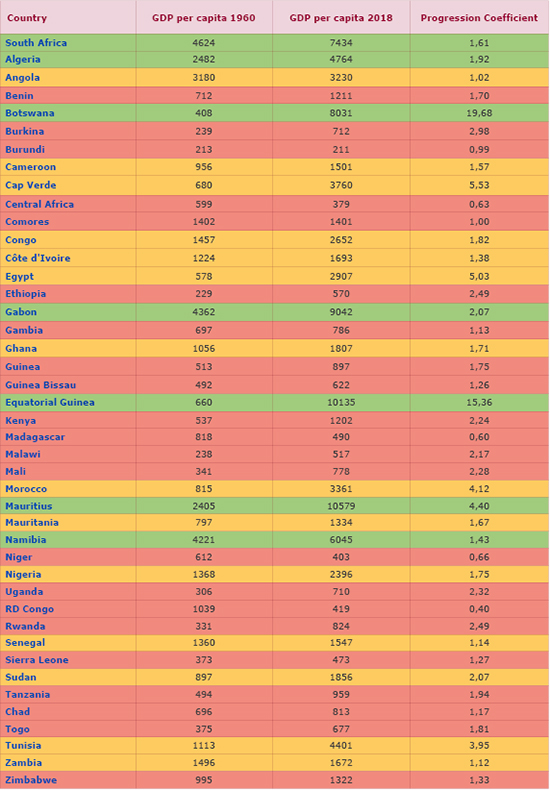

GDP per capita is a good criterion for assessing the average standard of living in a country. The University of Sherbrooke has calculated it in constant dollars for most countries since 1960, which enables comparisons to be made over time. It is all the more relevant since Sherbrooke introduced the so-called PPP (purchasing power parity) correction, which takes into account differences in purchasing power between currencies. The table in the appendix gives the value of GDP per capita in 1960 and 2018 for most African countries.

The African continent is still extremely poor

In 2018, Africa is the continent with the lowest average GDP per capita. Of the forty-three African countries for which fairly reliable statistics are available, twenty-three countries had a GDP per capita in 2018 of less than $1,500 and are in extreme poverty. Thirteen countries lie between $1500 and $4500 and have therefore not reached the level that Portugal had in 1960. Only seven countries lie between $4,500 and $10,000 per capita (Algeria, Botswana, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa).

Over the period 1960-2018, the GDP per capita of African countries grew less than in other continents. In six countries it has even declined: the populations of the Republic of Congo, Madagascar, Central African Republic, Niger, Burundi and Comoros are poorer in 2018 than they were in 1960.

In 1971, the World Bank created the category of LDCs, the least developed countries considered the poorest. At that time, fourteen of the twenty-six LDCs were in Africa. By 2017, out of forty-five LDCs, thirty-three are in Africa. There are currently 350 million poor people in Africa, with an estimated 250 million people who do not have enough to eat.

The failure of development in Africa is to be compared with the exceptional development of Asian countries. The best-known case is that of China, where GDP per capita rose from $192 in 1960 to $7,753 in 2018, a 40-fold increase. But we can also cite Singapore, which rose from $3503 in 1960 to $58,248 in 2018, surpassing countries such as France ($43,670 in 2018) or the United States ($54,659 in 2018). Highly populated countries such as India and Indonesia have managed to multiply their GDP per capita by 6: India increased from $330 in 1960 to $2,101 in 2018, Indonesia from $690 in 1960 to $4,285 in 2018. Other examples include Laos and Vietnam, which have quadrupled their GDP per capita, Malaysia by 9, Myanmar by 10, Thailand by 11 and South Korea by 28%.

Asia's success

Rather than seek explanations on the outside, it would be preferable to look at those provided by the African States themselves. The most pertinent study published in March 2020 entitled "Le Modèle Asiatique - Pourquoi l'Afrique devrait s'inspirer de l'Asie et ce qu'elle ne devrait pas faire" (The Asian Model, Why Africa should emulate Asia and what it should not do), was drafted by four authors who cannot be accused of being biased with regard to Africa: a former President of Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo, a former Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Hailemariam Desalegn and two South Africa academics, Greg Mills and Emily van der Merwe.

By studying the evolution of ten Asian countries since 1960, the authors first found that in 1960 Asian countries were not at an advantage compared to those in Africa, but that they implemented more effective economic policies. In most cases, the Asian countries first took measures in support of agricultural production: agrarian reform to give peasants a land tenure guarantee and the assurance of solvent outlets for their production. At the same time, they developed their training institutions, considering that investment in education was essential for the future. They then sought to develop an industrial sector, practicing openness to the outside world and relying on the competitiveness of private companies. Low wages and tax benefits for foreign companies helped attract investors.

Africa has privileged rather more its elites than its population

For the African authors of the "Asian Aspiration," the big difference between Asia and Africa is that in Asia development was achieved through investment in production by ensuring that "the benefits of growth were distributed beyond a small elite," whereas "African development was defined by clientelism, by managing elite access and preferences in exchange for support, leading to "rent-seeking" - the creation of wealth not through investment but through the connections of interest group organizations". Africa's problem is that "systems of governance are not inclusive and are fractured, fragmented or elitist, and characterized by rent-seeking, usually using ethno-political, racial or religious affinities."

What lessons can be learned of Europe's development aid to Africa?

The current situation in Africa, after decades of official development assistance, sweeps away the illusions of political leaders who think that it would be enough to launch a Marshall Plan for Africa to bring about its development. Europe must recognize that the development of a country and the improvement of the income of its inhabitants cannot be brought about by public development aid and that it depends first and foremost on the economic policy of the recipient country.

Foreign aid can only be a complement. Moreover, its importance must be put into perspective, because the amount of official development assistance is less than the amount of remittances from Africans in the diaspora and the amount of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

We should also remember that a 2020 report by UNCTED on "Illicit Financial Flows and Sustainable Development in Africas" estimates that illicit capital flight to Africa is at least $76 billion. In some African countries, a portion of official development assistance is used to fuel illicit flows.

Under these conditions, there are two solutions: either reduce or even eliminate official development assistance, or reform its objectives and methods to make it effective. If the development policy pursued by the recipient country does not meet the needs of its population, allocating aid to it serves at best only to feed a bottomless well, at worst to contribute to corruption.

The reduction of public development aid is not a solution

Even though official development assistance has not proven to be effective for Africa's development, now is not the time to diminish it. All European countries have been committed for decades to devote 0.7% of their GNI to official development assistance. Even if this international commitment is respected by only a few countries, a decrease in the amount of aid would degrade the international image of European countries. Moreover, it would be unwise to reduce aid to Africa after the Covid-19 pandemic, because in economic terms it is suffering severely from the consequences of the global recession.

Finally, it should be recalled that Africa will be increasingly affected by climate change and promises of aid from the Green Climate Fund remain largely unfulfilled. It is therefore necessary to maintain or even increase the amount of aid, but with a view to greater effectiveness than in the past. This requires a reflection on its objectives.

The present goals

In 2020, the European Commission proposed to redefine its strategy in Africa on the basis of five thematic partnerships:

1. Green transition and access to energy

2. Digital Transformation

3. Sustainable growth and jobs

4. Peace and governance

5. Migration and mobility

On June 30, 2020, the Council took up this strategy, tightening it around four themes:

1. Promotion of multilateralism

2. Peace, Security and Stability

3. Inclusive and sustainable development

4. Sustainable economic growth

All these objectives must seem very distant to African countries. For the majority of Africans, who are farmers and pastoralists, green transition or multilateralism are not their major problems. In fact, these objectives reflect European concerns and do not take into account African realities.

Expressed in less diplomatic terms, the main objective should be that all Africans become richer and live better. This is the best way to curb migration and develop mutually beneficial trade.

To achieve this, Europe should make clearer choices and help countries that seek higher incomes for all rather than countries that privilege predatory elites. This requires a discourse of truth about the economic policies pursued by many African countries.

A Europe that criticizes the economic policies of individual countries will immediately be accused of unacceptable interference. Some will remind it of Europe's colonial past, or the bad memories left by the "structural adjustment programs" imposed on African countries by the World Bank in the 1990s. To overcome these accusations, Europe can rely on the criticisms of Africans themselves, such as those made by the authors of the "Asian Model". In any case, Europe must do everything it can to try to stop the deterioration of the situation, because it is deeply affected: millions of young Africans, with little schooling, are entering a labour market that offers them few jobs. It is a situation that leads some young people to be tempted by illicit trafficking networks and groups linked to terrorism.

The first priority of African countries' economic policy and official development assistance must focus on agriculture. Although it accounts for only 14% of GDP, the agricultural sector employs half of the population in sub-Saharan Africa and, in the Sahel countries, more than three-quarters. The rapid growth of African cities should not obscure the fact that the rural population also continues to grow in the majority of African countries. To improve living standards, priority must be given to farmers and herders. This is the sector that can create the most jobs, in production, but also in upstream activities (mechanization, consulting) and downstream activities (packaging, first processing).

However, this has not been the priority of public development aid, which prioritizes health, social or public goods such as the environment. Neither has it been the priority of African governments, to the point that in 2003, the African Union became aware of the gap and prompted African States to commit to devote at least 10% of their budget to agriculture. However, in June 2014, the African Union found that a only small minority of countries had met the 10% commitment, with some countries such as oil-rich Nigeria devoting only 2% to agriculture.

"The Asian Aspiration" shows that successful Asian countries started with two priorities: agricultural development and education. In a 2020 UNCTAD report, Paul Akiwumi, Director of the Division for Africa, noting that 70% of ODA goes to the social sector, called for it to be channelled to the sector of production in the future.

Priority number one

To contribute to the development of the majority of the African population, the European Union should allocate at least half of its aid to African countries that are committed to a real agricultural development policy. This can be assessed by examining how they vote on their agricultural budgets, deal with the question of land tenure and give priority to local production.

The first sign of a good agricultural policy is the respect of budgetary commitment: an African country that devotes less than 10% of its budget to farmers and stockbreeders, who make up the majority of its active population, cannot say that it is pursuing a policy favourable to its development.

An educational policy favourable to agriculture must also be implemented. In many African countries, the profession of farmer has been shunned and the school system has pushed young people towards non-agricultural jobs, especially in the civil service. Since more than half of the young people are from rural areas and know their parents' farming techniques, the school should train them and encourage them to stay in the agricultural sector, particularly by instructing them in new agro-ecological practices. All African governments should strengthen the promotion of agricultural professions.

Helping African countries which address the issue of land tenure

Second criterion: addressing the land issue. The traditional system, in which a chief allocates a plot of land to a family each year, does not allow for any change in farming practices. A young African who wants to get involved in agriculture needs a long-term guarantee to invest in improving the productivity of his land.

While Asian countries - which have succeeded - have solved their land issues, African governments hesitate because such a policy clashes with ancient traditions and reduces the role of traditional chiefs. As the increase in population aggravates land conflicts between farmers and pastoralists, this makes this issue even more difficult to resolve. In practice, the longer one waits, the worse the problems become and the priority that an African government gives to agriculture can be measured by the way it deals with land issues. We should note that with aerial photos covering the whole of Africa, it is possible to produce a cadastre at low cost that is precise enough to solve the majority of land tenure problems.

Helping countries which privilege local production rather than imports

A third criterion of a good agricultural policy is the priority given to local production, which can be appreciated in particular with the policy toward rice. People living in African cities consume a lot of rice. To have social peace, it is in the interest of governments to keep its price as low as possible, and to do this, it is tempting to import rice or broken rice, which are often sold at low prices on the international market. Incidentally, the government collects customs duties, whereas to have local rice, it has to spend on infrastructure, training, access to fertilizers or roads. In the past and even now, many African governments have, without officially saying so, chosen imports rather than local production.

For cereal exporting countries (United States, European countries, Russia, Ukraine, Argentina), Africa is an essential outlet that they are keen to maintain. In the short term, many people stand to gain from this... except African farmers. To end this situation, the World Bank, together with the International Africa-Rice Research Centre helped many African countries to launch into National Strategy for the Development of Rice Growing (SNDR) in 2012 with a view of making local rice competitive with imported rice by 2025. In 2018, Africa Rice's Managing Director, Harold Roy-Macauley, acknowledged that rice production growth was insufficient, and that Africa imported 24 million tonnes of rice annually for a total cost of €6 billion. It is an illusion to think that African rice could be competitive with world prices over the next decade. In Europe, the Common Agricultural Policy developed after 1960 under a protectionist regime has guaranteed prices for farmers and export subsidies. Countries as different as Switzerland, Japan or the United States do not hesitate to put up customs barriers to protect their agricultural production.

African farmers would produce more if they had solvent outlets. Europe must put aside its preference for liberalism and competition and accept to help African countries that use agricultural protectionism to favour their farmers and stockbreeders, even if this creates difficulties with the United States, the World Bank and grain farmers.

African farmers and pastoralists will behave like entrepreneurs and will produce much more if they are sure to keep their land long enough and sell their production at a remunerative price. It is up to African governments and official development assistance to create an enabling environment for them in terms of advice, procurement, community facilities, storage, transport, etc., to ensure that they have access to the right tools and services.

The second major priority: education

Education has been the second priority of successful Asian countries. In Africa, there is much to be done to improve the education system. In sub-Saharan Africa, one child in five does not go to school. Beyond the age of 12, it is even one child in three, with an even higher proportion for girls. In areas marked by insecurity, in the Sahel, Congo, Central African Republic and Somalia, thousands of schools have closed. In many African countries, the level of teaching staff is low. Without improved training for men and women, Africa's development will not be fast enough to meet the needs of the population. Europe and other donors should concentrate much of their aid on the education sector.

The problem is not so much the construction of schools as the training and management of teachers and inspectors, which is currently the weak point of education policy. One of the most effective ways to improve this situation would be for official development assistance donors to commit to sustainable financing of teachers' salaries in certain areas of Africa. This is possible with the means of payment available on cell phones. Incidentally, this would make public schools more attractive than Koranic schools.

Include military spending

Much of Africa suffers from insecurity. Armed conflicts are ongoing in the Sahel and around Lake Chad, Libya, Somalia, South Sudan, Central African Republic, eastern Congo, Mozambique, Ethiopia. There can be no development without security. The budgets of African States do not allow them to develop sufficient military capabilities to control armed groups which know how to use the terrain as well as ethnic and religious rivalries. Moreover, the problem is not limited to terrorist or rebel groups. Rural Africans are even more affected by the banditry and racketeering they face on a daily basis.

The United Nations has military missions in Somalia, Congo, South Sudan, Central Africa, Western Sahara, and Darfur. Europe has military training missions (EUTM) in Mali, Central Africa and Somalia. France, with the help of some Member States, is financing Operation Barkhane, which involves five thousand men. Some European special forces have grouped together since 2020 to form the Task Force Takuba. All this represents a considerable budget. OECD donors have always refused to include military spending in official development assistance because they have fear it would be used for military coups. It is time to review this position, at least for some military spending, because restoring security is a prerequisite for development and a priority for both Europe and Africa.

European countries can effectively help Africans with intelligence, training, and the strengthening of their military equipment and capabilities. UAVs, for example, which are not used much in African armies, have become essential equipment for military operations. Military assistance from the Union and Member States should not be limited to the fight against armed groups but should also contribute to the strengthening of police and gendarmerie forces in order to improve day-to-day security.

Aid to so-called "fragile" or even "failed" LDCs

In some African countries, the State has virtually disappeared or controls only part of its territory. Examples include Somalia, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan. In other countries, such as Equatorial Guinea, the State merely exploits its mineral resources for the benefit of the presidential clan and does not seek to improve the situation of its inhabitants.

In these countries, the inhabitants are in great difficulty, but it is not desirable to channel official development assistance through State channels, as the risks of misappropriation are so great. Nobel Prize winners Esther Duflo and Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee propose a way to help the inhabitants directly. This would involve using cell phones, which are widespread in Africa, even in rural areas, to distribute money directly to the inhabitants. This type of action close to universal income or helicopter money has already been successfully experimented in Kenya. The Kenyan populations who benefited from regular monthly incomes used them for future investments.

Aid for industrialization

The "Asian model" emphasizes the importance of foreign investment. In this field, the action of private companies is essential. One of the main impediments to business investment in Africa is legal insecurity. European aid could be used to set up incentives or guarantee schemes, such as venture capital, adapted to each African country to facilitate investment by European companies in Africa.

For example, there is a huge need for electrification, but investments are often not profitable because consumers pay their bills only partially, or not at all. Companies could be encouraged to invest in electrification in countries that have a mechanism in place, with European support, to ensure the regular payment of electricity bills.

Aid for research

Research is an interesting field of action because the results obtained by researchers, even partial, are never lost. Stored in accessible databases, they can be used and completed by other researchers. In most African countries, researchers lack the means, whereas the development of their research would be interesting not only for Africans, but for scientists from all over the world. This is particularly true in the field of agricultural research, because climate change and the risks of soil fatigue are forcing us to find new cultivation methods that maintain or even improve soil fertility. Europe, with CTA in the Netherlands and the specialized French research organizations CIRAD and IRD, has the means to develop a thorough knowledge of African researchers and their research programs. These organisations should be able to propose the most interesting research programmes to ODA managers for financial and technical support in Africa.

Aid to decentralised cooperation

A number of European local authorities have engaged in international cooperation and partnership actions with African local authorities. These are often concrete projects that are decided after a discussion among local government representatives on an equal footing and are subject to an obligation of result, verified by periodic visits by partners. If there are no results, the project stops. As these are often small projects that sometimes involve only a small amount of money, official development assistance financiers, used to managing larger financial volumes, do not appreciate them because they feel that this type of small project takes up too much time.

A simple, effective solution would be for official development assistance managers to trust European local authorities and subsidize 50% of their decentralized cooperation projects with African local authorities. In addition, a 50% subsidy would facilitate decision-making in the municipal, departmental or regional councils of Europe, where it is not always easy to gain acceptance of the interest of an action concerning a distant country.

***

For sixty years, the Union and its member countries have been the main donors of official development assistance. In recent decades, they have devoted tens of billions of dollars yearly to African development. The result has been disappointing: Africa has remained a poor continent where the majority of the population has a per capita GDP of under $2000. The explanation given by Africans is that, unlike Asia, their governments have not pursued good economic policies. Instead of giving priority to agriculture and education, they have prioritized rent-seeking for the elites. Official development assistance cannot be effective under these conditions.

The current situation in Africa is serious. Its population growth is such that tens of millions of poorly trained young people are entering a labour market that offers them few prospects. This may lead them to be tempted by mafia or terrorist groups or to emigrate. It is in Europe's interest to help these young Africans find productive employment. Europe has set itself general objectives such as the green transition, digital transformation or the promotion of multilateralism. But these objectives, which correspond to the priorities of rich countries, are not adapted to the current situation of most African countries.

In Africa, the reality is that the agricultural sector employs half of the population and can create even more jobs for young people. In the Sahel region, three-quarters of the population lives from agriculture. It would be logical for Europe to devote at least half of its public development aid to farmers and stockbreeders and to give priority to countries that pursue a real policy of support for their agriculture. This is the best way to improve the income of a majority of Africans and it would also contribute to Africa's food sovereignty. This implies helping African countries where the government votes in a large budget for agriculture, allows farmers to have land for a sufficient period of time and protects them against imports of cheap agricultural products. If these conditions are not met, aid will be ineffective.

The second priority should be to contribute to the training of young people, which is a prerequisite for future development.

Next, official development assistance, whose increase has been decided upon, could set up specific mechanisms to support industrialization, strengthen research or support local authorities engaged in international cooperation actions. The increase in aid could also be an opportunity to conduct innovative experiments, such as the use of cell phones to distribute income directly to populations in need in certain countries. Finally, the insecurity that persists in many parts of Africa is a clear impediment to development. The military expenditures incurred by European countries to improve security in Africa are increasingly important and should be included, at least in part, in official development assistance.

ANNEX

Development 1960/2018 of the GDP per capita in Africa

Source : University of Sherbrooke

Key : Of 43 African countries, in 2018:

23 countries are below 1500 $ per capita

13 countries between 1500 $ and 4500 $ per capita

7 countries with more than 4500 $ per capita

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The EU and Globalisation

Olena Oliinyk

—

3 February 2026

Strategy, Security and Defence

Jean Mafart

—

27 January 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :