Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

-

Available versions :

EN

Bernard Bourget

Member of the French Academy of Agriculture

The farmers' protests of the winter 2025-2026 are an amplified replica of those of two years ago, mainly in France, due in particular to competition between, on the one hand, the FNSEA[1] (Fédération nationale des syndicats d’exploitants agricoles) and the Young Farmers, and on the other hand, the very aggressive Coordination Rurale and the Confédération Paysanne.

These protests focused on two issues:

- The management of the contagious nodular dermatitis (CND) crisis, more specifically the opposition to the slaughter of all infected herds, even though this radical method has proven effective in Savoie and Haute-Savoie, where it has eradicated the disease.

- The free trade agreement between the European Union and the four MERCOSUR countries (Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay), which is currently awaiting approval.

It is also the expression of a deep unease among French farmers, who have faced a series of difficulties in recent years that have not been experienced with the same intensity by their counterparts in other Member States. The causes of these difficulties therefore need to be analyzed.

In Jean-Luc Demarty’s opinion[2], the main cause is the loss of competitiveness of French agriculture on the European market, which is reflected in an increase in agricultural income in France of only 17% between 2010 and 2024, well below the European average (77%) and that of Spain (79%), Poland (86%) or Italy (170%).

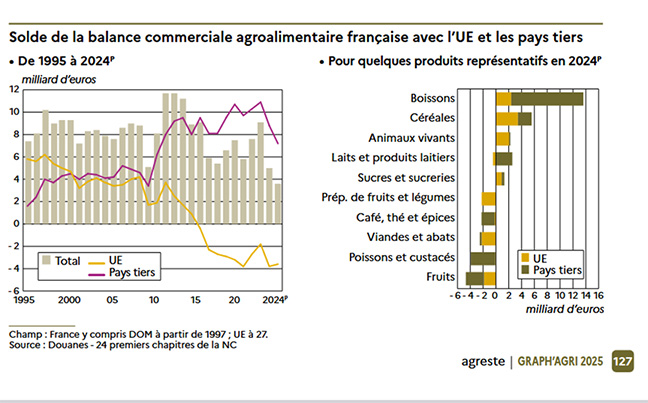

The reasons why the agri-food trade balance of France has collapsed must also be examined. It was only positive of 200 Million euros in 2025.

In recent years, French agriculture has had to grapple with health, climate and economic crises.

The health crises have affected cattle (epizootic haemorrhagic disease and contagious nodular dermatosis), sheep (bluetongue) and poultry farms (avian influenza), while pig farms are still threatened by African swine fever.

Climate change is having a severe impact on French agriculture, with successive droughts, floods and spring frosts.

While health and climate crises also affect agriculture in other Member States, it is in the area of foreign trade that French agriculture is clearly hardest hit, particularly by moves by China and the United States to target wines and spirits, the leading export item for the French agri-food industry. The cereal sector, which is the second largest agri-food export item, is suffering from competition from the Black Sea countries and, above all, from Russia's offensive for wheat on African markets. The Algerian market was thus lost in 2025 in the context of that country's dispute with France, while the price of wheat is currently below $200 per tonne, (below the average production cost for French farmers), and the European Commission wants to tax imports of nitrogen fertilisers from Russia and Belarus as part of the carbon border adjustment mechanism.

The loss of competitiveness of French agriculture within the European Union

The trend in France's agri-food balance of trade has shown a worrying deterioration within the European Union since the early 2010s.

The successive enlargements of the European Union to include Spain and Portugal, then the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, which have significantly lower labour costs than France and have benefited from European aid to modernise their agriculture and food industries, explain, at least in part, France's loss of market share within the European Union. The boom in Polish agriculture is a striking illustration of this.

Other factors have contributed to the loss of competitiveness of French agriculture: Member States with labour costs as high as France, such as Denmark, the Netherlands and even Germany, have increased their agricultural and food exports to the European market. Explanation: in these countries, economies of scale have been achieved by enlarging livestock facilities (cattle sheds, pig farms, poultry houses).

The processing and marketing of low-cost products from Mercosur countries (GM maize and soya) and Ukraine (sunflowers, chickens) transiting through the port of Rotterdam have also contributed to making the Netherlands the European champion of agri-food exports.

In a book published in 2011, I demonstrated that the lack of agreement on GMO crops in Europe had led to an absurd situation, since the European Union imports large quantities of GMO products, while severely restricting their cultivation. France has been particularly zealous in this regard, banning all GMO crops on its territory.

The over-transposition of European directives and the (too) numerous French regulations are also highly detrimental to our agriculture and are sometimes Kafkaesque, as demonstrated by the rules imposed on farmers regarding the size of hedges.

French agriculture is not adapting quickly enough to market changes: by favouring products with labels or designations of origin, it has ceded the market for low-cost food products, which consumers prefer to buy, to imports, as is the case with chicken.

Faced with pressure on prices from large retailers, which have European purchasing centres located outside France, the French authorities have sought to rebalance trade relations in favour of farmers through laws known as Egalim. After three successive Egalim laws, the results are disappointing, as farmers' incomes have not really improved and trade relations have not been smoothed over. Small and medium-sized food businesses, which are numerous in rural areas, are caught between powerful supermarket chains and farmers whose prices are guaranteed by law.

Mercosur and Ukraine

French farmers are at the forefront of opposition to the free trade agreement between the European Union and the four Mercosur countries (Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay) because they have the most to lose.

Indeed, suckler cattle farming (with beef breeds such as Charolais and Limousin), which is specific to France and Ireland, will have to contend with increased imports of meat from Mercosur countries, produced on large farms at much lower costs. The European Commission's argument that the 99,000-tonne quota represents less than 2% of European production is not acceptable, as the imports will be of prime cuts, such as sirloin, which will compete directly with French production, and because beef consumption is declining in Europe.

The other quotas granted to Mercosur countries in the free trade agreement concern the jewels of French agriculture, in particular beet sugar, which will face fierce competition from Brazilian cane sugar, which is exempt from customs duties. The opportunities offered for European wines, spirits and dairy products, as well as the recognition of a few geographical indications, fall far short of compensating for the advantages granted to Mercosur agricultural products.

What is particularly shocking is that producer countries in Mercosur will not be required to comply with the rules, particularly those pertaining to the environment, to which European producers are subject, as there are no ‘mirror’ clauses in the WTO provisions. Yet the European Commission intends to scrupulously comply with these provisions, which are being flouted by the United States and China.

The European Commission should instead take inspiration from the proposal put forward by Laval University in Quebec[3] that aims to balance trade agreements by adding the environmental and social dimensions of sustainable development to the purely economic dimension. The European Union could therefore include the three dimensions of sustainable development in its trade agreements with third countries.

The advantages envisaged for Mercosur countries are all the more worrying given that they come ahead of those granted to Ukraine for the same products, notably poultry, maize, wheat, soya and sugar, to which must be added sunflower oil, of which Ukraine is the world's leading exporter. However, Ukrainian agriculture has very large agro-holdings of tens or even hundreds of thousands of hectares, which have much lower production costs than farms in France and Western Europe, where the average size is still less than 100 hectares.

The Green Deal and the Common Agricultural Policy

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, made environmental and climate issues a priority of her first term and, in 2020, as part of the Green Deal, presented two strategies that clash with the CAP negotiations for 2023 to 2027: the ‘farm to fork’ and the biodiversity strategies.

The latter immediately led to questions and criticism following converging expert reports, including that of the European Union's Joint Research Centre, showing that they could lead to sharp declines in European agricultural production of more than 10%.

These strategies were part of a punitive and degrowth approach to European agriculture. In addition, some of their objectives were unrealistic, such as the one concerning organic farming (25% of agricultural land by 2030), or contrary to the European Union's food sovereignty, such as the withdrawal of 10% of agricultural land from production.

The decline of the Green parties in the June 2024 European Parliament elections led the European Commission to scale back its legislative and regulatory ambitions for the implementation of these two strategies, as it is clear that the necessary ecological transition of agriculture will not happen without the support of farmers and without giving them the means to achieve it. A change in the Commission's approach has been therefore necessary to replace constraints with incentives.

In July 2025, the Commission presented its proposals for the future Common Agricultural Policy for the years 2028 to 2034, together with those concerning the European Union's financial programming for this period.

The main change concerns the transformation of the European Union's budget architecture, with the abandonment of the two pillars of the CAP and the merger of funding for agriculture with that of the cohesion funds into a large economic, social and territorial cohesion fund. To benefit from this fund, each Member State will have to prepare a national and regional partnership plan (NRPP) in line with the European Commission's guidelines, which will be approved by the Commission.

The main consequences of this new architecture would be:

- A dilution of CAP appropriations within this large fund.

- Greater flexibility for Member States in determining how to allocate the appropriations assigned to them.

- Strengthened powers for the Commission, which will negotiate with each Member State and monitor the implementation of their plans.

However, the Commission has planned to guarantee €300 billion over the period for direct aid to farmers, which still accounts for nearly three-quarters of CAP appropriations. This amount represents a decrease of around 20% compared to the current programming. However, this decrease is due to be less than expected following the announcement by the President of the Commission in January 2026, of an additional €45 billion to secure Italy's support for the majority of Member States that have approved the free trade agreement with Mercosur countries.

The proposal that is likely to be debated the most concerns the decrease in direct aid over €25,000 and its capping at €100,000 per farm per year. The Commission had already proposed gradual decreases and capping in previous programmes. However, this met with hostility from Germany[4] and countries in Central and Eastern Europe, which support large farms that transitioned from communism to capitalism after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

However, gradual decreases and capping of direct aid are more necessary than ever in the context of a constrained budget so as to ensure a fairer distribution of this aid, while preserving the income of the many medium-sized farms in France and other West European countries, freeing up funding for the ecological and digital transition of agriculture, and preparing for Ukraine's accession to the European Union. To overcome opposition to gradual decreases and capping of direct aid, the Commission may be prompted to raise thresholds and spread their application over several years.

Other proposals from the Commission include:

- Replacing “cross-compliance” requirements with targeted environmental and climate incentive measures, particularly in the context of farm transition plans.

- Doubling the budget for crisis management.

- Increased support for generational renewal with the creation of a start-up kit for young farmers.

- The creation of a new sector for protein crops, which should be largely based on legumes, whose environmental benefits are undeniable, but whose success will depend on the sector's ability to compete with imports of soya and soya meal from the United States and Mercosur countries.

- The renewal of European programmes for the distribution of fruit and vegetables in schools, the implementation conditions for which should be simplified.

Negotiations on the CAP for the years 2028 to 2034 have only just begun and could last for many months.

The conditions for recovery

The recovery of French agriculture will depend first and foremost on itself, based on a clear-headed analysis of the challenges it faces on the one hand, and its strengths and weaknesses on the other.

Among the challenges facing French agriculture, the following are worth noting:

- The ecological transition, which is still not sufficiently advanced, and adaptation to climate change.

- The modernisation of farms and control of their production costs, within the framework of free trade agreements, competition from third countries with powerful agricultural sectors that benefit from the opening up of the European market, but also those still to be conquered in these countries.

- Competition from other Member States' agricultural sectors in the European single market.

- Increasing price volatility in agricultural markets.

French agriculture has several assets at its disposal to meet these challenges:

- Its training and research apparatus (INRAE), as well as its technical institutes.

- Its flagship seed industry.

- Land prices that are lower than in northern European countries.

- A wide variety of terroirs and products, which benefit from numerous designations of origin.

- A renowned gastronomy.

- Relatively abundant water resources.

However, it is hampered by excessive regulation; excessive mechanisation and labour costs; it lacks in terms of organisation, and adaptation to changing consumer expectations and a spirit of conquest in external markets, both within and outside Europe.

The measures taken to remove obstacles to the construction of production facilities, particularly poultry houses, so that they can reach a size equivalent to those of their European competitors, are a step in the right direction.

Authorisations for the construction of water reserves should help France catch up with its European neighbours, develop controlled irrigation and cope with summer droughts, which are becoming increasingly frequent and severe.

France must also make better use of the resources made available to it by the European Union to:

- Strengthen producer organisations and their ability to negotiate with large retailers and food companies, to reduce the deficit in the fruit and vegetable sector, with the help of better implementation in France of the European programme for the distribution of fruit and vegetables in schools.

- Develop the use of insurance and mutual funds to guarantee farmers' incomes against climatic, health and market risks.

As soon as the European regulation on new biotechnologies[5] has been adopted, French agriculture and the seed industry should be able to use these to adapt plants to climate change and strengthen disease resistance.

The decline of our agriculture is part of a more general decline in the French economy, characterised by a significant trade deficit and the disappearance of entire sectors of our country's industry.

The recovery that took place at the beginning of the Fifth Republic, with the implementation of the plan developed by Jacques Rueff, shows the way forward.

[1] The French national farmers union

[2] Jean-Luc DEMARTY was successively Director-General for Agriculture and External Trade at the European Commission

[3] The proposal concerns a draft international convention on agricultural and food diversity and sustainability.

[4] In Germany, these are the large farms in the former eastern Länder.

[5] This is mutagenesis, which accelerates natural mutations.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Régis Genté

—

10 March 2026

Gender equality

Helen Levy

—

3 March 2026

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

European Identities

Patrice Cardot

—

10 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :