Democracy and citizenship

Thierry Chopin

-

Available versions :

EN

Thierry Chopin

European identity: an "intermediary" identity between the national and the global

Geographic identity that is difficult to grasp

The term "European" involves geographic, historic and cultural factors that contribute, to varying degrees, in forging a European identity based on shared historical links, ideas and values - but without this cancelling out of course our national identities.

Europe is surrounded by seas in the North, the West and the South, but there is no obvious geographical limit to the European project in the East. Moreover, all projects for unification and perpetual peace from the 18th century on (Abbé de Saint Pierre, Kant) were part of a cosmopolitical rationale. Europe's geographical identity is understood in broad terms: the Organisation for Security and Peace in Europe (OSCE) includes 57 countries from Vancouver to Vladivostok; the Council of Europe has 47 members, including Russia and Turkey. Moreover, the continued enlargement of the European Union looks more like a process of indefinite extension than the definition of a territorial framework, which is vital however for the development of a collective identity.

In this regard it seems that we should stress the absence of the word "territory" from the Union's founding legal texts and from its primary law[4]. Territory is mainly associated with the States comprising the Union only. Unlike "territory", "area" is extremely present in Europe's primary and secondary law: in the Preamble of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and in the Union's objectives there is mention of the establishment of "an area of freedom, security and justice without any internal borders", as well as the construction of an "internal market (...) comprising an area without internal borders (...)". Moreover, beyond the territories of the States that are European Union members, this seems to be typified by areas which have specific functions: money, free-trade, security, justice etc. This juxtaposition, even interlacing, of functional areas leads to differentiated types of integration which then lead to a segmented, geometrically variable area: the internal market (28 Member States, 27 after the Brexit); the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU 19 members); the Schengen Area (22 Member States and 4 associate States - Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) etc. Not only does differentiation like this create a degree of legal complexity but it also leads to a problem of legibility and in turn, one of political legitimacy in the eyes of the citizens. Lastly, the European Union is typified by an "area of rights" which refers to the values[5] that have been at the heart of the Union's enlargement process and the extension of the European area. In spite of the fact that the treaties mention the European nature of the candidate States wishing to join, article 49 of the TEU simply specifies that "any European State which respects the values referred to in Article 2 and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union." The dynamic of enlargement has relied on the dissemination of democratic principles and the rule of law, as well as Western democratic, constitutional practices fostered by the membership conditions set in the treaties.

A "Europe" of values ?

The Union is founded on a community of values set down in the treaties: the respect of human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and the respect of Human Rights. These values are shared by the Member States in a society typified by pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between men and women[6]. Naturally the Member States have specific national identities and histories and this "Europe of Values" does not mean that borders have been abolished. Moreover, a series of surveys undertaken since 1981 in Europe (European Values Surveys) has led to the distinction of four circles within the "Europe of Values", matching collective preferences that are more or less pronounced around which groups of States converge[7]. Finally it is clear that the nation is still the vital framework of political reference for most Europeans[8].

It now seems possible to speak of a core of European values that bring together part of Europe and comprise the base of a joint political identity[9], and this, in spite of the specific nature of this value or another linked to the political and national culture of one country or another. The case of secularity and religious freedom is an example of this. Naturally, as far as Europe is concerned the nature of relations between Church and the State is variable from one Member State to another. France is the only Member State to have included secularity in its Constitution; in this manner it is the only original model in that the other States have not introduced the separation of the Churches and the State as strictly as this. The UK is not a secular country because it has an official religion (the Queen is the head of the Anglican Church). The Orthodox Church enjoys a specific status within the Greek Constitution; etc. And yet, European societies distinguish themselves by a high degree of secularisation (possibly Ireland and Poland apart) and stand out from other Western countries, like the USA, which is a secular country (assertion of the separation of the Church and the State) but which acknowledges the significant place that religion occupies in the public sphere. This difference in terms of secularisation undoubtedly helps us take on board the differences in how the media addressed the attacks in Paris in January 2015 and the caricatures on the European continent and in the Anglo-Saxon world (or to be more precise in at least a part of it)[10]. This analysis could be extended by highlighting the differences in collective preference between Europeans and Americans, for example, in terms of their relationship with violence and arms; moreover the upkeep of the death penalty in certain American States also helps us distinguish the two sides of the Atlantic within the Western world[11]. In spite of this specific feature of European identity in terms of values, it remains that the latter often seem too abstract to provide an adequate response in terms of founding a particular identity, understood in the sense of a feeling of belonging to a group with which it members can identify, as being the "same" - the etymology of identity is "idem".

Common cultural identity and national plurality

After Greek and then Roman Antiquity, Europe became an objective historic reality which "arose when the Roman Empire collapsed" (Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre) around a certain number of elements such as the Church, and feudalism - the Court, the town, religious orders, universities (Bologna, Prague, Oxford and Paris) - which provide a unity to European culture. But at the same time, there is a duality at the heart of European identity, between the existence of a common culture and the political fragmentation that goes with it[12]. This duality can be found in each stage of the European spirit's development process[13]. On the one hand there is the factor of community that provides Europe with its unifying framework: Renaissance and Reform, the scientific revolution, the Baroque Crescent, from Rome to Prague, classical art, the Republic of Letters and then the Enlightenment etc. It is in this sense that Europe is "a nation comprising several" (Montesquieu). On the other hand, there is the factor of "particularity" with the creation of nations in France and England, the national revolutions of 1830 and 1848, the Italian and German unifications, etc. This national plurality led to competition which formed the core of European dynamic as soon as Charlemagne's empire was divided, with each king wanting to be the "emperor of his own kingdom." Europe invested a political model, that of the Nation State, which substituted that of the city (for which Athens provided the model) and of the Empire (embodied by Rome). This competition took various shapes: from emulation to the foundation of European dynamism to rivalry and conflict, which explains the tragedy of the wars throughout Europe's history.

It is possibly in this link between these two elements (cultural unity and national particularities) that we find part of the answer that the European Union might use to settle the issue of identity in the present globalised world: "The identity of Europe is necessarily of an intermediate nature: it must accept economically and from a human point of view, to be both part of a globalised whole and comprise Nation-States that retain their discrete identities. Europe's specific vocation dictates its identity and vice-versa. This identity involves finding a middle road between the global and the local, between dilution and self-withdrawal, to avoid, as much as possible, a brutal confrontation between world interdependence and blind, xenophobic, sterile isolation"[14].

Responding to the identity deficit: what is to be done ?

Identity, history and borders

Beyond public policy that should be developed in terms of the learning of languages (as written by Timothy Garton Ash: "the heart of the democratic problem in Europe, it is not Brussels, it's Babel"[15]) and mobility[16] responding to Europe's identity deficit first involves a strategy that aims to provide its citizens with points of reference in time and space[17].

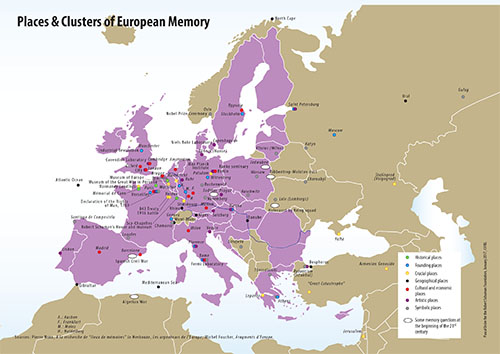

Indeed it means implementing the teaching of true European history. This does not mean "replacing national narratives, which remain vital in the education of young people" but they have to be complemented with a "specifically European narrative in which the young Europeans will learn that every national historical phenomenon was also and primarily European; "Europeans should learn about shared places of memory and heroes - without obscuring the things that have torn Europe apart, and the crimes, since we can build nothing good on a lie, even by omission. But by showing how, based on a shared memory of past ills, a joint will to build a better future can emerge. This is not a bad definition of a true policy for European identity."[18]Then the issue of borders is central and is raised with particular acuity. Some States feel that their security is threatened on their borders (the Baltic countries and in the East by Russia in particular) and doubt the Union's ability to protect them, which is leading to more national military spending (in Poland) or a strengthened integration strategy (the Baltic countries with the adoption of the euro, seen as a guarantee of greater solidarity). The question is vital: if Russia undertook an aggressive, expansionist policy as in Ukraine against a Member State, what would the Union do? This would be the true test for the borders and European identity. Are we ready to engage means and take the risk of losing human lives to protect our collective borders?

Beyond the aspect of security, the question of the borders introduces the aspect of identity: that which links the nations within the Union together is also what distinguishes them on the outside, and the distinction between "a within" and "from without" is constitutive of a sense s of identity. The question of the borders is therefore linked to that of the Union's political and geopolitical identity and involves a multinational collective whole[19]. Of course we have to reassert the geopolitical contribution made by the various enlargements to European integration in terms of pacification, reconciliation, and the stabilisation of the continent[20], and this in spite of worrying developments in Central Europe. Yet, we have to acknowledge that unlike the previous enlargements, those since 2004 have gone together with questions, not just of a political-institutional and socio-economic nature, but especially of identity which have risen up in several national public opinions (in France and the Netherlands, but also in Germany and Austria). Beyond the economic (fears of social and tax dumping amplified by the crisis) and political reasons (feeling of a loss of influence), the question of identity is linked to the geopolitical divide caused by the fall of the Berlin Wall. On the one hand this identity crisis originates in the feeling of an apparently indefinite extension that typified a limitless Europe which although vital, has not managed to take the issue of territory seriously (limits of security, definition of a community as a framework for belonging and identification)[21]. On the other hand there is the geopolitical split that was introduced with the collapse of the Soviet Union 25 years ago, which has brought to light a unique factor: the contact with the periphery of the European continent, where it seems that work of clarification, albeit temporary, is required regarding the territorial limits of the European Union[22].

In this kind of context it is essential to start thinking politically about the Union's limits. This vital question has been avoided for too long on the pretext that it was an issue that divided Europeans (notably regarding which status to offer Turkey and Ukraine)[23]. By not asking this question it means that we are not responding to the discomfort of public opinion on this issue, a discomfort that it contributing to a weakening in support for European integration.

"We" defending against threats

The founding principles of our regimes of freedom have to be revived and reasserted as a matter of extreme urgency as the recent attacks in various countries of Europe have so tragically reminded us. Indeed, whilst we have felt that we rediscovered freedom (of speech, the press, of thought) as a powerful vehicle for social links after the attacks in January 2015 in Paris, many citizens feel threatened in terms of their individual freedom and notably their security. The challenges made to European internal and external security may be a factor to use to strengthen the feeling of belonging to a common whole.

Although European integration has freed the European States of a rationale of permanent power struggles, it is not enough to free them of external constraints. At the same time other regional entities do not have the same problem: in spite of the relativization of their power the USA relies on an extremely strong patriotism, the defence of their world leadership and well identified interests; China relies on a balance found in Confucian tradition, the Communist State and mercantilist strategy. In other words the USA and China have a system of values and an understanding of the world, patriotism, at the heart of an identity which enables united, resolute action, as well as an awareness of their collective interests, which does not seem to be the case with the Union and its Member States.

Why is there this asymmetry? Because for Europe "the most decisive aspect is undoubtedly of vital essence: it is internal dynamism, its ability to adapt without betrayal to innovate and yet consenting to openness, to discuss and cooperate with the other without losing its identity (...). What is lacking is on the one hand vital impetus, self-confidence, ambition, and on the other, awareness of its unity. If elsewhere people get passionate, Europeans are not very passionate, not about their joint project in all events; passions exist within the nations, but they often tend to be defensive or negative. It is a European ambition that has to be created or revived. But this in turn cannot come from a State, it must be open both to the nations that comprise Europe and to the world which surrounds it and from which it cannot isolate itself"[24]. In other words it means reviving European pride and confidence, starting with reasserting the principles that form the heart of what they are.

But as Luuk van Middelar rightly said "historically Europe has only been half prepared for a task like this. The Founders pursued two goals at the same time. Was the unification of Europe a project of peace or project of power? (...) As part of a project of peace Europe is "an eminently moral act" supported by the desire for reconciliation and by idealism. As a project of power European integration is a political act based on conviction and involving the redefinition of the participants own interests. In the first case national citizens must become stateless citizens of the world (or depoliticised consumers); in the second instance, they must become committed Europeans and even be proud of their identities. In other words the project of peace demands the sacrifice of national identities to the benefit of universal values, whilst the project of power demands the development of a European identity"[25].

***

Although they belong to different national traditions and histories the EU Member States share values, principles and interests as the core of their identity, which distinguishes them from other countries and regions of the world, whether this involves China and Russia, but also the USA. It is because the European Union will constantly show that it implements decisions and policies in line with these principles that it will be able to persuade its citizens more convincingly of its use and its legitimacy in facing the challenges of the present world.

[1] This text was originally printed in 'Schuman Report on Europe, the state of the Union 2017', Editions Lignes de Repères, March 2017.

[2] T. Chopin, "The Populist Moment: are we moving toward a post-liberal Europe?" European Issue n°414, Robert Schuman Foundation, December 2016.

[3] P. Perrineau, Les croisés de la société fermée. L'Europe des extrêmes droites, Editions de l'Aube, 2001. The expression "open society" has been borrowed from K. Popper, The Open Society and its Enemies (1945)

[4] E. Cartier, "L'UE: une construction atellurique", international seminar, Faculty for Legal, Political and Social Sciences of the University of Lille 2 (CRDP / ERDP), 11th and 12th April 2013.

[5] Cf. the preamble of TEU: "Drawing inspiration from the cultural, religious and humanist inheritance of Europe, from which have developed the universal values of the inviolable and inalienable rights of the human person, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law".

[6] TEU, article 2

[7] O. Galland et Y. Lemel, " Les frontières de valeurs en Europe ", in Bréchon and Gonthier (dir.), Les valeurs des Européens. Evolutions et clivages, Armand Colin, 2014.

[8] Eurobarometer Standard 84 Survey, Autumn 2015 Although an absolute majority of Europeans have a dual sense of nationality, both national and European, 51% of those interviewed define themselves first by their nationality, then by the European citizenship; in addition to this 5% of Europeans first see themselves as Europeans, then as citizens of their country, finally only 1% feel that they are European.

[9] Cf. Eurobarometer Standard Survey 85, Spring 2016. Two Europeans in three say they feel that they are citizens of the European Union (67%), whilst barely one third of them do not agree with this statement (31%); moreover in 26 Member States those interviewed who feel that they are citizens of the EU are in the majority. Finally we should stress that more of those interviewed living in the euro zone feel that they are European citizens: 68% against 64% outside of the euro zone (EB Standard 84, op. cit.)

[10] J. Turley, "The biggest threat to French free speech isn't terrorism. It's the government", Washington Post, 8th January 2015 and D. Carvajal and S. Daley, "Proud to Offend, Charlie Hebdo Carries Torch of Political Provocation", New York Times, 7th January 2015.

[11] B. Tertrais, " Europe / Etats-Unis : valeurs communes ou divorce culturel ? ", Robert Schuman Foundation Paper n°36, 2006.

[12] E. Barnavi, " Identité ", Dictionnaire critique de l'Union européenne, Armand Colin, 2008.

[13] L. Jaume, Qu'est-ce que l'esprit européen ?, Flammarion, " Champs essais ", 2009.

[14] P. Hassner, "The Paradoxes of European Identity", Englesberg Seminar, June 2012.

15] T. Garton Ash, "Europe's real problem is Babel", The Guardian, 18th October 2007.

[16] T. Chopin, " Les relations complexes entre mobilité et identité européenne ", in " Encourager la mobilité des jeunes en Europe ", Rapport du Centre d'Analyse et Stratégique, n°15, La documentation française, 2008, p. 118-127.

[17] Eurobarometer Standard 84, op. cit. To the question "in your opinion amongst the following areas which create a sense of community the most amongst citizens of the EU?" those interviewed answer: culture (28%); history (24%), sports (22%), economy (21%), values (21%), geography (20%) the rule of law (17%), languages (14%), solidarity with the poorest regions (14%), inventions, sciences and technology (13%), and healthcare, education, retirement pensions (11%). Religion comes last (9%)

[18] E. Barnavi, " Identité ", op. cit., and. P. Nora, " Les 'lieux de mémoire' dans la culture européenne ", in Europe sans rivage. De l'identité culturelle européenne, Albin Michel, 1988, p. 38-42.

[19] T. Chopin, " L'Union européenne, une démocratie sans territoire ? ", in Cités, Presses universitaires de France, n°60, 2014, p. 159-167. See also Etienne François, Thomas Serrier (dir.), Europa. Notre histoire. L'héritage européen depuis Homère, Les Arènes, 2017.

[20] L. Macek, L'élargissement met-il en péril le projet européen ?, La documentation française, 2011.

[21] P. Hassner, " Ni sang ni sol ? Crise de l'Europe et dialectique de la territorialité ", in Culture et Conflits, n°21-22, 1996, p. 115-131.

[22] M. Foucher, Le retour des frontières, CNRS Editions, 2016 et L'Obsession des frontières, Perrin, 2007.

[23] Les partisans de l'adhésion de la Turquie avaient obtenu que la question des " frontières de l'Europe " n'apparaisse pas dans le mandat du groupe de réflexion sur " l'Europe en 2030 " que l'ancien président du gouvernement espagnol, Felipe Gonzalez avait présidé en 2010.

[24] P. Hassner, " Préface ", in P. Esper (et. alii), Un monde sans Europe ?, Paris, Fayard / Conseil économique de la Défense, 2011, pp. 29-30.

[25] L. van Middelaar, "Pourquoi forger un récit européen ? La politique identitaire en Europe. Nécessités et contraintes d'un récit commun", in A. Arjakovsky (dir.), Histoire de la conscience européenne, Editions Salvator, " Collège des Bernardins ", 2016, p. 31-56.

Publishing Director : Pascale Joannin

To go further

Future and outlook

Régis Genté

—

10 March 2026

Gender equality

Helen Levy

—

3 March 2026

Future and outlook

Veronica Anghel

—

24 February 2026

Agriculture

Bernard Bourget

—

17 February 2026

The Letter

Schuman

European news of the week

Unique in its genre, with its 200,000 subscribers and its editions in 6 languages (French, English, German, Spanish, Polish and Ukrainian), it has brought to you, for 15 years, a summary of European news, more needed now than ever

Versions :